50

L

ocated in south west Africa, with a

population of 2.3 million and larger than

Britain and France combined, Namibia

exudes a barren sense of wilderness.

The epitome of this aridity, the coastal Namib

Desert occupies the country’s entire western

margin, some 1,000 miles long with varying

widths of up to 125 miles.

But in more ways than one, this harsh

environment is a rich storyboard of evolution

and with only a slight scratching of the surface,

a wealth of life is discovered.

Big Daddy, the goliath sand dune, which I had

just summited, as well as others of similar

standing, are located in the central west portion

of the Namib in an area known as Sossusvlei.

Translated in English to ‘dead-end marsh’,

Sossusvlei is one of four large clay pans that

form the end point of the ephemeral Tsauchab

River.

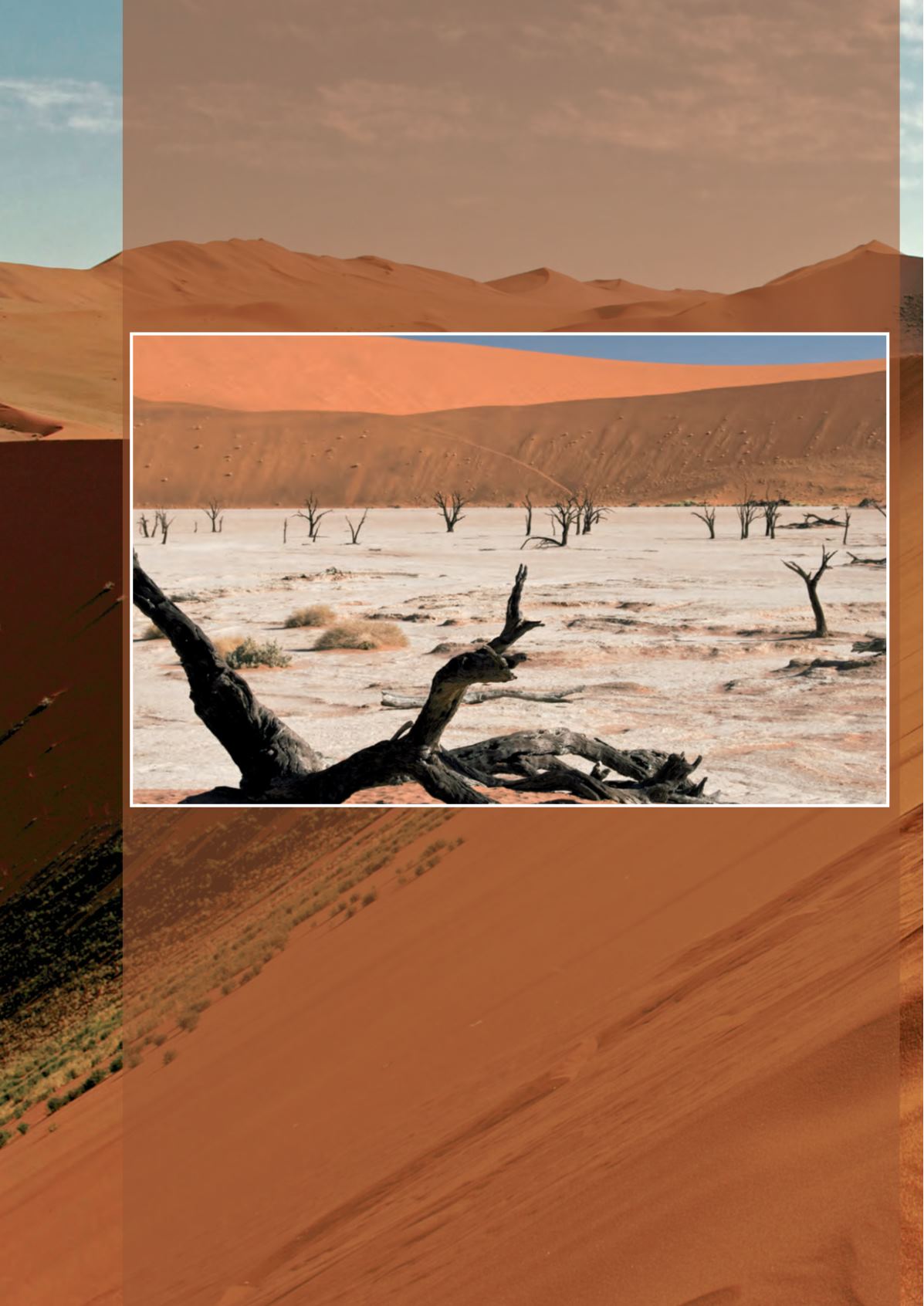

The flat, deathlywhite of the pans surrounded

by towering red sand dunes offer some of the

most striking natural landscapes to be found

anywhere in Africa.

Another must see, literally ‘over the dune’ from

Sossusvlei, is a parched pan named Deadvlei.

Here a small dead forest of camel-thorn trees

has been fossilised for some 900 years, relics

of a time before the sand sea halted seasonal

floods.

Venturing into the rockier northern Namib

via some rusty shipwrecks and thousands of

sea shells on the Skeleton Coast, I arrived at

Desert Rhino Camp to see for myself just how

large mammals such as the black rhino can

survive in the desert.

Run in conjunction with the local communities

and Save The Rhino Trust (SRT), this long-

standing, highly successful operation has

managed to sustain the largest, free-roaming

population of these critically endangered

animals on earth.

Another early morning saw me follow the SRT

Trackers as they scouted dry riverbeds with

their binoculars.

We soon saw a mother and her calf making

their way down to one of the few natural

springs in the area, stopping off to browse at

various dead-looking shrubs.

While these individuals didn’t look too different

from black rhino I had seen elsewhere in

Africa, they are internationally recognised as

a separate ‘desert’ species; feeding and

moving mostly at night and resting in shade

during the day.

Unlike other rhino, they have a much greater

utilisation of available food, browsing 74 of the

103 plant species that occur in their range, and

moving much greater distances for both food

and water, some having territories of more than

500 square miles.

Perhaps the highlight of my trip was navigating

further north through the Skeleton Coast

Deser t Delight

JAKE COOK goes on an African adventure across Namibia,

observing first-hand conservation work and experiencing the

true wilderness of the Namib desert