word) sounds the closest to anything he's done

previously – a little of his

Wild Is the Wind

vocal

from

Station to Station

as filtered through a

melody akin to Psychedelic Furs'

Sister Europe

– but in truth this is all new territory.

A standout is Lazarus (released as a single in

December and the title piece of his forthcoming

theatre production of

The Man Who Fell to

Earth

) where he adopts his most intimate voice,

like a tone poem of increasing desperation.

And what's he on about on

Blackstar

?

Themes of alienation, religion and fear abound,

but close reading isn't rewarding because it

sounds like he's using the cut-up method.

In

Lazarus

you may decipher references to

A

lthough we've had almost half a century

of the unexpected from David Bowie,

few, if any, could have anticipated his

remarkable new album, , AKA

Blackstar

.

It bears no resemblance to its brittle and

abrasive predecessor of three years ago,

The Next Day

, and there’s scant reference

to anything in his vast catalogue of diversity.

Longtime Bowiephiles might mutter, “Hmmm,

Outside

perhaps?” or “That bit sounds like

something off

Black Tie White Noise

”, but

mostly they're kidding themselves.

Perhaps its closest reference point might

be the stuttering electro-shivers of FKA twigs,

except Bowie is more musically ambitious and

deploys jazz musicians to paint in

the widescreen subterranean bass

and astonishing drum work from

players who shift emphasis and

tempo. At times it's as if he’s called

up the spirits of performers like

Don Cherry and Ornette Coleman,

but brought in an academy-trained

drum'n'bass crew and taken them

on a left turn into art music.

Three of the seven songs

have appeared previously: the

shapeshifting 10-minute title track

which opens the album (helluva

challenge to start with) moves

from a claustrophobic mood over

skittering drums and onward

through languid sax. The second,

Sue (Or In a Season of Crime)

, was

on the 2014 collection

Nothing Has

Changed

, however this new, more

aggressive version has splinters of

guitar piercing it. The third is ‘

Tis a

Pity She’s a Whore

, which originally

appeared as the B-side to the 12-

inch release of

Sue

, however it has

also been re-recorded for

Blackstar

.

But neither prepare you for the

breathtaking scope of Bowie's

musical and lyrical vision here. The

extraordinary final song

I Can't Give

Everything Away

(with a tellingly

lengthy pause before the final

himself, his brother who committed suicide in

’85, and/or John Lennon. Or not.

Blackstar

isn't for those who partied to

Let's Dance,

and maybe not even those who

immersed themselves in the sonic textures

of

Low/”Heroes”

, but it's quite remarkable,

and because it exists outside the wide musical

landscape he previously staked out, it drives

you to look deeply into his last 20 years for hints

that

Blackstar

might be on the horizon.

There's nothing, but a search allows a

rediscovery of the underrated

1.Outside

(1995) with Brian Eno which – the first of an

incomplete conceptual series – sprung

The

Heart's Filthy Lesson

and

Hallo Spaceboy

(remixed by the Pet Shop Boys). Over

disconcerting sonic beds from Tin Machine

guitarist Reeves Gabriel, jazz drummer

Joey Barron and others, Bowie declaims a

cyberworld in decline.

The downward spiral went

unfinished because for his next

album,

Earthling

(1997), he

embraced drum'n'bass, jungle

and industrial sounds. It remains

one of his most interesting

albums (with Trent Reznor on

hand for

I'm Afraid of Americans

)

but went past most people who

only remember the distressed Union

Jack(et) he wore on the cover.

When

Hours

(1999) rolled around,

many former fans had moved on

(fair enough, it wasn't that good), so

most missed the excellent

Heathen

(2002) where he covered Neil Young's

I've Been Waiting For You

and had

a near-hit with the fascinating and

melancholy

Everyone Says “Hi”.

That album and the patchy

Reality

(2003) reunited him with producer

Tony Visconti, who got the call

for

The Next Day

which appeared

unannounced in 2013, and now the

exceptional

Blackstar

.

At 69, David Bowie is still delivering

the unexpected and in that regard

“nothing has changed”.

But with

Blackstar

, everything has

changed.

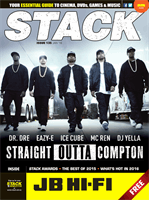

Graham Reid considers David Bowie's new

album and his recent past.

HALLO AGAIN

SPACEBOY

Its closest reference

point might be the

stuttering electro-shivers

of FKA twigs

• Blackstar by David Bowie is out January 8 via Sonyvisit

stack.net.auMUSIC

FEATURE

60

jbhifi.com.auJANUARY

2016

MUSIC

For more reviews, interviews and

overviews by Graham Reid:

www.elsewhere.co.nz