ROUSES.COM

ROUSES.COM

9

Chef Nathan RIchard

W

hen chef Nathan Richard scans the meat

case at Rouses in Thibodaux where he

teaches at the John Folse Culinary School,

or in New Orleans, where he lives and works, he sees the

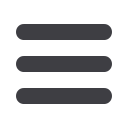

bigger picture. Pork chops are part of a loin roast on the

upper back of a grain-fed pig. He can imagine the rib

structure that holds them in place and the fatback a bit

higher on the hog. He can look at Rouses pork section

and knows the best way to cook any part of a pig.

After talking with Chef Nathan for a while about pigs,

pork and possibilities, you start to see his well-developed

superpower. While most cooks see the world of pork

from a pan perspective, Richard sees the same pig with

Cajun-influenced butcher-vision.

The common cuts — what are known as the “primals” in

meat-cutting circles — are just the beginning.

Richard’s special way of seeing things becomes obvious

as the Thibodaux native talks about his cooking, his

approach and the way that he learned about food.

Years before he took his first kitchen job peeling potatoes

and shrimp at Commander’s Palace to get through

college, Richard learned about Louisiana cooking

traditions in more practical ways. “My dad was the chef

of the family, and I learned a lot from him,” he said. “I

was young and wanted to hunt, but my parents didn’t,

and they weren’t going to pay to get the deer processed.

It was expensive, so I bought myself a meat grinder and

learned how to break deer down myself.”

Richard’s full-animal education continued thanks to a

penchant for whole-hog cookery he learned from his

grandfather in nearby Raceland.

“Cooking whole hogs was a celebration in my family,”

he said. “So when I was about 18, we decided to try one

out at Lake Verret. We went and got a pig from the

stockyard and tried it

out.Wethought

we had a clue, but not really,”

he laughed. “We had some beer and a fire. We figured we could

make something happen.”

Before hitting restaurant kitchens as his life’s work, he embarked

on an early career as a firefighter and paramedic — studying Fire

Science Technology at Delgado Community College. After being

trained as a first responder and arson investigator — no, really —

Richard became a captain of theThibodaux Fire Department at age

21. Over time, his professional interests shifted to restaurant work.

His 5-year stint at Commander’s under Executive Chef Tory

McPhail led to a tour of renowned kitchens across the South,

most notably in South Carolina. In Charleston, Richard worked

with renowned chefs Sean Brock, Mike Lata, and Frank Lee (at

McCrady’s, FIG and High Cotton, respectively). He also studied

charcuterie in France and Italy. Returning home to Louisiana,

he opened the Lafayette location of Donald Link and Steven

Stryjewski’s Cochon and did stints at White Oak Plantation and

John Folse’s Revolution as a full-time butcher.

But take one look at the menu board at Richard’s latest gig —

Kingfish — and you’ll see the dedication to making the most of the

whole animal, whether it’s from the barnyard or the bayou.

“We buy whole animals and work our way through it with hourly

specials.We’ll get a pig and make head cheese and offer it as ‘Offal of

the Hour.’When it’s gone, it’s gone.Then we’ll make pork backbone

stew and offer

that

as a special. And when it’s gone, it’s

gone.Wedo

the same thing with seafood. Catfish head stew, grouper heads and

collars. It’s a sign of respect to use the whole animal.”

He also teaches what he preaches to culinary students atThibodaux’s

Nicholls State University, where he leads whole-animal butchery

classes at the Culinary Institute. The next generation of restaurant

chefs get to learn the craft of breaking down and appreciating the

whole animal.

“It’s my job as a chef to educate, tell people what it’s

about,” he said. “With the class, I start out on

the first day with a whole alligator, and we

use every bit of it.”