CBA RECORD

31

Running from the Police

Holmes was born in San Diego, California,

and moved to Chicago at a young age. She

grew up the oldest of five children in a five-

bedroom house in the south side Morgan

Park neighborhood. Just at the end of her

block was Calumet City, Illinois. When

they moved in, her family was the first

African American family on the block—a

fact that triggered some violent reactions

in some of her neighbors. “I can tell you

stories,” Judge Holmes says, “[but] I won’t

tell you.”

Eventually, the neighborhood, as she

describes it “turned over,” and filled with

children playing softball in the street.

“Our big kick,” Holmes says, “was at 10

o’clock at night, we would go to the end of

the block and cross the street because the

curfew in Calumet City was 10 o’clock,

but the curfew in Chicago was 10:30. So

we would cross the street, and the Calumet

City police would come and turn on the

lights and we’d run back across the street.

And we literally would do that, you know,

for a half an hour.”

She later learned that the officer who

chased her and her siblings across the

street was the husband of Holmes’ sixth

grade teacher. “He was having just as

much fun as we were.” Even so, when her

mother found out about Holmes’ nightly

shenanigans, the game quickly ended.

Holmes describes her mother as an activist

and a rabble-rouser–a title which Holmes

also proudly claims. Holmes’ mother had

graduated from high school at 16 years old

and went straight to college. She became a

buyer for Sears & Robuck, located in the

now-named Willis Tower, where Holmes’

current office is.

The Education of a Rabble-Rouser

Holmes graduated valedictorian from

Edward H. White elementary school.

Her mother fought hard to get her into

the then-new George Henry Corliss High

School. In her freshman year of high

school, Holmes sat front and center in

her advanced placement English class.

The teacher took one look at her and

asked, “Why are you sitting in the front

of my class? You’re too black, too dumb

to be in front of my class. Get up and go

back.” Holmes, as she describes her skin

color, is “chocolate.” Because it was the

only advanced placement English section

offered, Holmes couldn’t switch out of

the class. “Which meant that me and the

teacher were going at it over every comma,”

Holmes recalled, “every period, every

noun. But it made me a better writer. Not

that that’s the way you go about it.”

Judge Holmes graduated co-Valedic-

torian from Corliss High School, tied in

almost every respect with another student.

Holmes recalls arguing with the school

about whether she should have to share

the title at all, noting that she had a perfect

attendance record while her so-called co-

valedictorian did not. “I think that was my

first legal argument,” she quips.

For college, though she was accepted or

waitlisted at Stanford, Harvard, and other

top schools, Holmes chose the University

of Illinois because it was the least expensive

and close to home. She started off in engi-

neering, but later switched to the liberal

arts. “I was the only minority, only African

American, only female [in Engineering]. I

couldn’t get anybody to study with me. I

was lonely…so I switched out.”

On campus, Holmes came into her role

as a rabble-rouser like her mother, never let-

ting injustice pass by unchecked. “I had to

learn how to stick up for myself,” she says.

During her freshman year rhetoric class,

Holmes was “the only black person in the

class, the only visible minority.” One story

from that class has stayed with her. Papers

in the class were graded anonymously, with

only social security numbers identifying

the students. When handing back graded

papers in class, Holmes’ professor slid her a

paper without reading off any of the iden-

tifying numbers. Holmes remembers the

moment clear as day. “How did she know

this was my paper?” She thought, “She

must know my social security number…

Then I looked at the paper and it said ‘F’

… I’ve never failed anything in my life.”

The paper wasn’t hers. Holmes had actually

received an A+, and the professor had even

written on Holmes’ paper

Use as example

.

Before giving Holmes her actual paper, the

professor asked her, “Who helped you with

this?” Holmes promptly switched out of that

section. “Dealing with situations like that…

always made me the person who says ‘That’s

not right. That’s not fair. We’re standing up.’”

Her college friends dared Holmes to

take the LSAT. Though she didn’t study

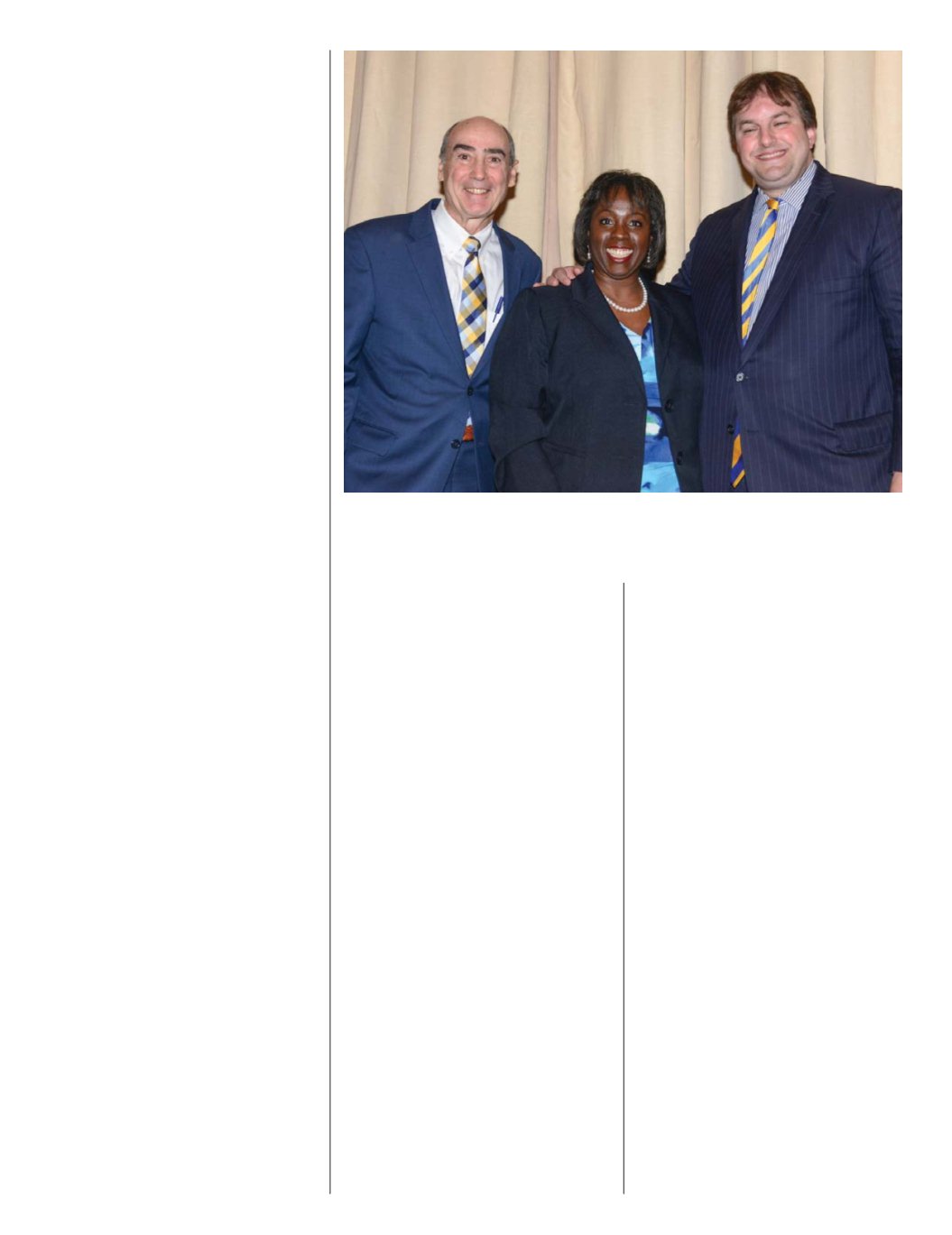

At the CBA’s Annual Meeting, shortly after receiving the gavel of leadership fromDaniel

A. Cotter of Butler Rubin (right), with CBA Executive Director Terrence M. Murphy.