21

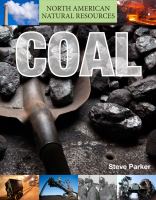

Chapter Two: Mining Coal

As information mounts about the area, depth, and quality of the coal seams,

the mining company decides if and when to begin mining. Mine planners make many

decisions, including which kinds of surface or underground mining to carry out, what

machinery needed, and where to put access roads and camps for the workers. They

must also gauge the effects of the mine on the local surroundings and environment,

get permission from landowners, determine the likelihood of people protesting,

costs, time schedules, and how much coal might sell for when it arrives, among other

aspects of the operation.

Surface Mining

At a surface mine, any layer of soil and rocks, called the

overburden

, is removed

to reveal the coal. Enormous machines like diggers, bulldozers, and excavators lift

and move the overburden, which is usually stored to put back later when the area is

repaired or “rehabilitated.” Explosives may loosen very hard rock.

Then

excavators

start to cut away the coal. Dragline excavators are like cranes

with a vast bucket at the front, which is lowered to the surface and then pulled

toward the excavator with a dragline so it gouges up the coal. The excavator

swings around and dumps the coal onto a conveyor or waiting truck, then turns

back to take another bite. Bucket-wheel excavators have a huge rotating wheel

with many buckets, on the end of a long arm. The arm swings against the vertical

coal “cliff ” or face and eats its way in, with the coal falling onto a conveyor. The

whole excavator moves along on tank-like caterpillar tracks or huge “feet.”

Big Muskie

Dragline excavators for coal mines are among the biggest moveable machines

ever built. Ohio’s “Big Muskie” was almost 400 feet (120 meters) long, 222 feet

(68 meters) high, and weighed over 13,000 tons (11,800 metric tons). Its bucket

held more than 300 tons (270 metric tons) of coal. It was in action from 1969 to

1991, when it was retired because the mines it worked produced coal unsuited

to new environmental laws. In 1999, “Big Muskie” was cut up, providing

enough steel to make the equivalent of 9,000 cars.