22

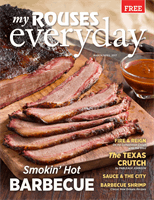

MY

ROUSES

EVERYDAY

MARCH | APRIL 2017

the

Barbecue

issue

W

hen it comes to traditional foods (and especially

barbecue), I can’t help but admire the purists. I tip

my hat to folks who become enamored with the

transcendent flavor of their favorite ’cue, then are driven to perfect

it as part of their home repertoire. As students of the craft, they’ll

travel the country to sample the legendary pits.

Purists take their excitement for barbecue and funnel it into long

smoke sessions and copious note-taking. They’ll spend whole

holiday weekends patiently tending their backyard cookers with

patience and precision. They fixate on the finer points of the

seemingly simple craft (rub recipes, meat trimming, pit physics)

and spend countless hours tending their meats, controlling every

variable in the process.

As a barbecue lover, I respect a purist’s dedication, and it’s a joy

to gorge on the tasty fruits of their obsessive labor. As a cook, I

like their ambition and determination. But as a practitioner of the

barbecue arts, I’m more of a realist.

When I cook pork shoulders, I don’t obsessively check my meat

temperature or fiddle with airflow during a 9-hour smoking session.

Instead, I lean pretty heavily on something called the “Texas Crutch.”

And my life is much better for it.

The Basics:

In Competition

The Texas Crutch is a smoking technique that involves wrapping

a partially smoked cut of meat (usually a brisket, pork shoulder or

other roast-like hunk) in thick aluminum foil to concentrate heat,

accelerate cooking, and minimize evaporation. Add a little liquid to

the mix (beer always works) and let it sit for a spell.

In basic kitchen terms, the basic crutch technique turns a dry-

cooking method (smoking) into a wet-cooking method (essentially

a braise). It’s also a great way to turn an economical cut of pig (the

notoriously tough pork shoulder) into fall-apart shreds of delicious

piggy barbecue.

The “wrap and rest” technique developed on the national barbecue

competition circuit, where control of internal temperature and meat

moisture is critical.

Competition pitmasters track the doneness (and the final texture) of

barbecue by tracking its internal temperature. For big cuts of meat

(brisket, shoulders), there’s a “plateau”in the process —where cooking

seems to stop as the heat penetrates deep into the center of the meat.

Over time, slow heat gradually transforms the connective tissue and

muscle of the traditionally tough meat into silky, flavorful collagen

— the rich “X factor” of your favorite stews and gravies.

The

Texas Crutch

by

Pableaux Johnson