36

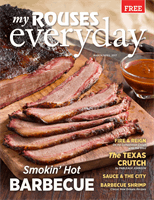

MY

ROUSES

EVERYDAY

MARCH | APRIL 2017

the

Barbecue

issue

I

n a country, and world, that seems to

grow ever more contentious and us-

versus-them, is there no common

ground? No place in which we can all rest?

Yes. Cornbread. Everybody loves cornbread.

I know. I spent six years writing a book

about cornbread. When I answered the

question, “What are you working on?”

the response was instant. “Cornbread? I

love

cornbread!” It was not only the words

that were near-universal, it was the tone:

delighted surprise, as if reminded of a pure

pleasure rarely thought of, almost forgotten,

yet greeted as an old, dear friend.

So, yes. Cornbread is a meeting place.

That’s why all of us should have a good

cornbread recipe. It’s so very simple to

make. Given this, and given the near-

universal happiness it gives, why would

you deny yourself that rarest of pleasures,

delighting others?

Because cornbread is also a place of dissent.

Not everybody loves the same kind of

cornbread. Sugar, or not? Bacon fat, or

butter? Yellow cornmeal,or white? Universal

agreement on what makes cornbread love-

worthy does not exist. Disagreement about

cornbread, like so much, is just as common

as love for it.

Most professed cornbread lovers have a

cornbread that is to them the one and only

good, real, true, authentic version, against

which all others are sham. “If God had

meant cornbread to have sugar in it, He’d

have called it cake,” cookbook author/

culinary memoirist Ronni Lundy said

tartly. She’s been saying so for decades

(since the 1980s, when she first wrote about

the subject for

Esquire

). The author of the

recently published

Victuals: An Appalachian

Journey, with Recipes

, Lundy is the latest

in a long line of those throwing down the

cornbread gauntlet, a lineage that includes

Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson,

Frederick Douglass and Mark Twain.

Like many other my-way-is-best beliefs,

cornbread loyalties often lie in our

childhoods, the region where we spent

them, and our race. Mostly, the cornbread

we grew up with is the one to which we give

allegiance and love.

Our rationales follow. Lundy recently told

the

Charlotte Observer

,“…we don’t put sugar

or flour in our cornbread in the mountain

South …those were things we’d have to buy

…be beholdened to someone for. Your daily

bread was things you could grow yourself …

the bread of my … forebears resonates for

me culturally as an act of independence …

an individual’s ability to feed him or herself.”

One cannot help but admire this line of

thinking and self-sufficiency; yet Lundy’s

skillet-baked cornbread contains baking

soda, presumably purchased. The truly

self-reliant cornbreads came earlier. Most

of today’s eaters would not recognize

them as cornbread: these breadstuffs were

unleavened cakes of cornmeal, water, and

salt — no milk, buttermilk, eggs. (These

were often called hoecakes or ashcakes,

because they were baked on the side of a

hoe over the fire, or in the ashes themselves).

When such cakes were made from the

finely ground cornmeal possible only when

the corn to be ground had been alkalized

(as Native Americans did, using ground

clamshells, ash, or chamisa bush, among

many other pH-altering agents), they were

… tortillas. (Since the Native Americans

were here first, and corn is the Americas’

Corn

Bread

fed

by

Crescent Dragonwagon