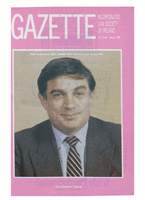

GAZETTE

SEPTEMBER 1989

Interview with

Thomas Finlay

Chief Justice, Supreme Court

The following is the text of an interview with the Hon.

Mr. Justice Thomas Finlay, Chief Justice, which was

published in a book entitled

"Judging The World: Law

and Politics in the World's leading Courts"

by Gary

Sturgess and Philip Chubb, published by Butterworths

in 1988. It is reprinted with kind permission of the

publishers.

Interviewer

Appointments

to the bench are controlled by the

executive and a lot of Irish appointments seem to have

been of people who have formerly been politicians, or

connected with political parties. Is that good or bad?

Thomes Finlay

Speaking in ideal terms, it is a bad thing. In a perfect

society one should be able to devise a better method

of appointing the judiciary. I would have thought,

however, that in my experience - as with many

apparently unjustifiable theoretical procedures - it

has worked extremely well. I can't remember any

example of a person appointed to a judicial post of any

importance in my time (and I came to the Bar in the

mid '40s) whose previous political loyalty had the

slightest effect on his judgments or in any way

affected his capacity, as it were, to stand up for the

individual against the existing government. At the end

of the day somebody must be accountable for the

standard and type of judiciary that is appointed. There

is a significant amount to be said for making politicians

accountable for it. They are the ones to whom the

people in general can turn if bad judicial appointments

are being made. If appointments are made by some

body of people who are relatively anonymous then

there is no one to turn to and to blame.

Is the political life of judges before they come to the

judiciary helpful in offering a breadth of experience?

I think it is rather a help. I myself was an active

politician for a number of years; I was a member of

Dáil Éireann for three years. I was appointed to the

High Court Bench by the party I had opposed and I

have subsequently been appointed to other posts, to

the Presidency of the High Court and to the Chief

Justiceship, by the party with which I had been

associated. I think my experience in politics gave me

a general, broad approach to matters and, like any

other experience, probably helps you as a judge.

To what extent would you say that judges are

political?

It depends on the sense in which you are using the

term political. I think that a person's politics consists

of a whole bundle of thoughts and philosophies apart

from adherence to a party. He may be a person who

is naturally conservative; he may be a person with a

very considerable regard for the rights of the individual,

a regard that is greater and deeper than his regard for

law and order. There are all sorts of balances of

political approach in any person who is interested in

politics. In so far as that is so, that there can be politics

with a small 'p', I think that, necessarily, every judge

must have a bundle of these ideas and philosophies.

They are bound to have some effect, though they

should never be allowed to dominate his judgments.

But I don't think this makes him political in the bad

sense. It doesn't make him a part of a political party,

nor does it mean that because he is conservative on

one point he is going to be conservative on another.

I don't accept, certainly as far as the Irish judiciary

is concerned, and particularly the Court of which I am

the President, that there is a clear-cut cleavage

between a right and left wing of the Court. The

magazine commentators love this, but I don't believe

it is true. It's much easier to write about the Court if

you proceed on that basis, but in fact I think the

performance of the judges shows that they approach

individual cases in a different and individual way.

Where do you place the Supreme Court as an

institution of government?

We have a constitutional theory called the

separation of powers. The separation of powers

consists essentially of the executive - the

government of the day and all its officers, the

legislature - the two houses and the President, and

then the judiciary - the third separate power. I would

have thought that in regard to the ordinary conditions

of life, though not so much the economic of course,

the judiciary, and in particular, the Supreme Court as

the court of ultimate appeal, is contributing as much

to the nuances of life in Ireland today as either of the

two other separated powers of the Constitution.

How much do you think the Supreme Court has

affected Irish society?

I suppose it has had two impacts, one of which was

negative, h At periods in our history we have had a very

disturbed country. There have been times when the

enforcement of law and order became the sole

objective, certainly a very dominant objective, of

successive governments. At that time the Supreme

Court, I would have thought, had a massively

important negative role - protecting people against

an excessive encroachment on their personal rights.

In more recent times, while that is still a very

important aspect of the work of the Court, I suppose

you could say that there is a positive aspect too,

involving less dramatic rights of the individual. The

right of privacy is one, also certain economic rights

arising from the ownership of property. We have

constitutional guarantees against the failure of the

State to protect property rights. These have become

the subject matter of decisions by the Supreme Court

in more recent times and, I would hope, they have

made a major contribution to the fairness of society.

242