GAZETTE

OCTOBER 1989

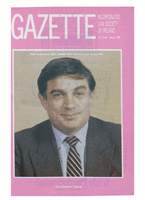

Judging the world

Interview with Brian Walsh

Justice, Supreme Court; Judge, European Court of

Human Rights.

The following is the text of an

interview with the Hon. IS/lr. Justice

Brian Walsh, Judge, European

Court of Human Rights, which was

published in a book entitled

Judging the World: Law and Politics

in the World's leading Courts

by

Gary Sturgess and Philip Chubb,

published by Butterworths in 1988.

It is reprinted with kind permission

of the publishers.

Interviewer

What was the basis of your

being selected to serve on the

Irish court?

Brian Walsh

When the Prime Minister offered

me the appointment he said he

would just like to mention one thing

- he would never again refer to it -

but he said he would like the

Supreme Court to become more

like the United States Supreme

Court. So I pointed out to him there

were certain differences. But that

was his general idea. I understand,

from what I learned subsequently,

that he said much the same thing

to the new Chief Justice, who was

appointed the same day. That was

the late Cearbhall O Dalaigh.

Obviously it was t he Prime

Minister's wish that the court

should be more active in its

interpretative role. It was put very

briefly but quite clearly. I am not

saying that necessarily influenced

me in any particular way, because

I think the horse was chosen for the

course. He probably felt he was

taking to somebody who had much

the same views. I certainly was

very much influenced by the

American experience. I had studied

it to a very considerable extent and

kept myself familiar with it all

through my career.

You were very young, forty-two.

Why did you accept the appoint-

ment?

I had been a very active practitioner

but I was also very interested in

law. I thought I would like to be in

the position of being able to decide

the legal issues without having to

fight for one particular side of it. So

it put me in a position where I could

make a more objective contribution

towards the development of law,

particularly constitutional law,

which was a particular interest of

mine.

What happened in the partner-

ship between you and the Chief

Justice?

No t h i ng t hat was designed

happened. It was just that each of

us had this particular outlook and,

as we constituted two-fifths of the

court and the others were not un-

sympathetic to our point of view, it

was a question of making the

running. And in most cases the

other judges, or most of them,

would agree. It was really a case of

what I might call a newer and

younger generation of judges

coming in. To that extent the judges

were probably more forward-looking

in the field of constitutional de-

velopment, in giving life to a

Constitution which, in the early

days perhaps, had been regarded

as an o r nament rather t han

something of actual practical utility.

From 1961 onwards the Consti-

tution became very much part of

life and its impact could be felt

among the ordinary people, who

suddenly became conscious of the

fact that they had a Constitution,

that it could be implemented and

that, in fact, many parts of it were

self-executing and did not require

any supporting legislation. The

consciousness of this suddenly

burst upon the public and it just

happened to be that, in the years

commencing around about 1960-

61, the court, for a variety of

reasons, became very active. The

most important reason was that it

got the cases. The court is not self-

starting and depends on cases. So

it was a happy coincidence of the

right cases coming along at a time

when the court was most receptive

to new ideas.

The court may not be self-

starting, but in cases which may

have little relevance to the

Constitution you can still

develop the constitutional law

by focusing on what may be

peripheral issues and then

bringing them to the centre. Do

you agree?

Yes, that can be done. To use

modern parlance, one can put

\

Brian Walsh.

3 48