10

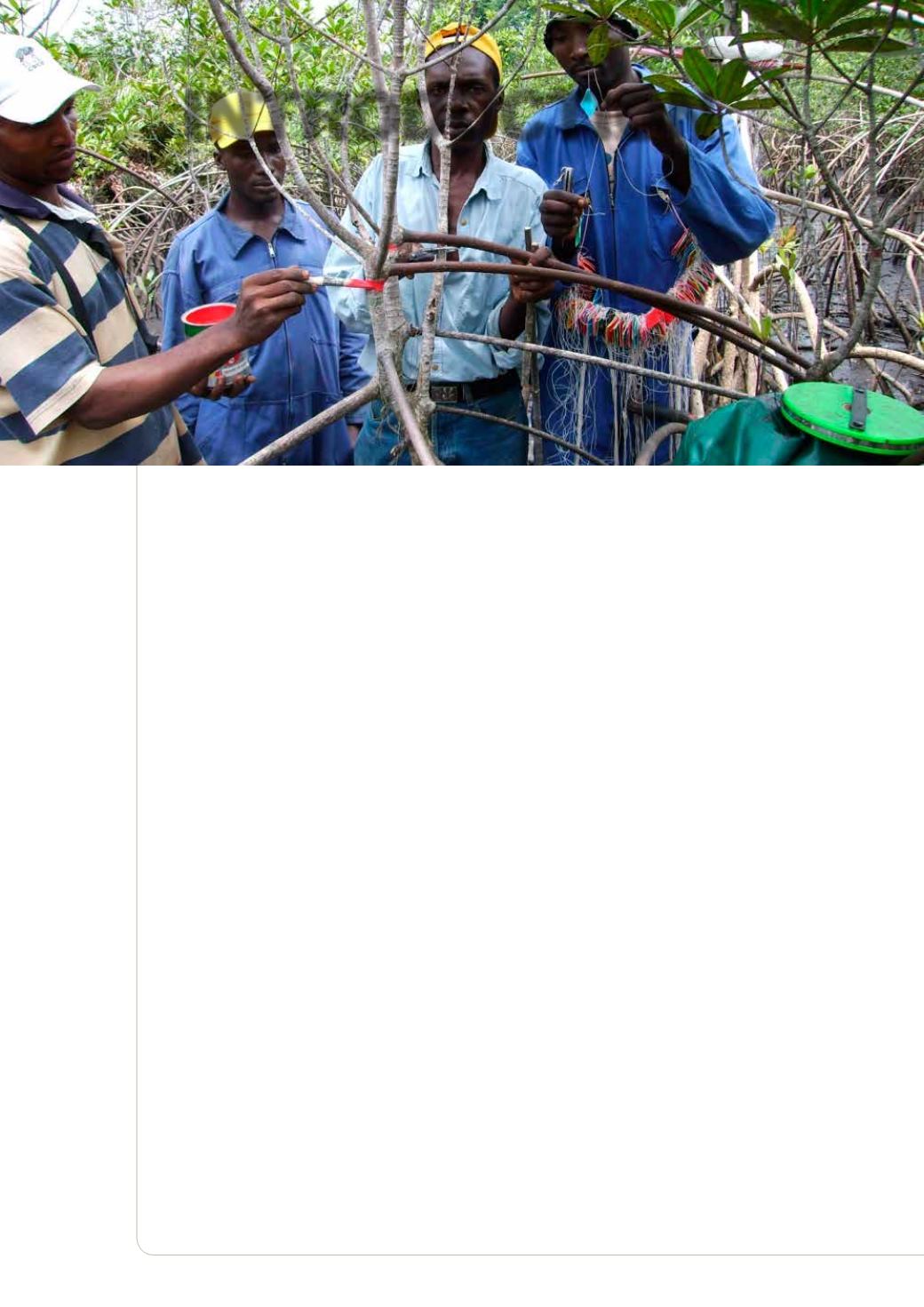

Mangrove forests along the west coast

of Central Africa, including Cameroon,

Equatorial

Guinea,

Sao

Tome

and

Principe, Gabon, Republic of Congo (RoC),

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and

Angola covered approximately 4,373 km

2

in 2007; representing 12.8% of the African

mangroves or 3.2% of the total mangrove

area in the world (UNEP-WCMC, 2007).

According to a UNEP-WCMC (2007) report,

20-30% of mangroves in Central Africa were

degraded or lost between 1980 and 2000.

Major threats in the region include increasing

coastal populations, uncontrolled urbanization,

exploitation of mangroves for firewood, housing

and fishing, pollution from hydrocarbon

exploitation and oil and gas exploration. The

consequences of current rates of mangrove

deforestation and degradation in Central Africa

are important as they threaten the livelihood

security of coastal people and reduce the

resilience of mangroves.

Recent findings indicate that mangroves

sequester several times more carbon per unit

area than any productive terrestrial forest

(Donato et al., 2011). Although mangroves

cover only around 0.7% (approximately 137,760

km

2

) of global tropical forests (Giri et al., 2010),

degradationofmangroveecosystemspotentially

contributes 0.02 – 0.12 Pg carbon emissions per

year, equivalent of up to 10% of total emissions

fromdeforestation globally (Donato et al., 2011).

In addition, mangroves provide a range of other

social and environmental benefits including

regulating services (protection of coastlines

from storm surges, erosion and floods; land

stabilization by trapping sediments; and water

quality maintenance), provisioning services

(subsistence and commercial fisheries; honey;

fuelwood; building materials; and traditional

medicines), cultural services (tourism, recreation

and spiritual appreciation) and supporting

services (cycling of nutrients and habitats for

species). For many communities living in their

vicinity, mangroves provide a vital source of

income and resources from natural products

and as fishing grounds. Multiple benefits

that mangrove ecosystems provide are thus

remarkable for livelihoods, food security and

climate change adaptation. It is no wonder that

the Total Economic Value of mangroves has

been estimated at USD 9,900 per ha per year by

Costanza et al., (1997) or USD 27,264–35,921 per

ha per year by Sathirathai and Barbier (2001).

However, loss and transformation of mangrove

areas in the tropics is affecting local livelihood

through shortage of firewood and building

poles, reduction in fisheries and increased

erosion. Recent global estimates indicate that

there are about 137,760 km

2

of mangrove in

the world; distributed in 118 tropical and sub-

tropical countries (Giri et al., 2010). The decline

of these spatially limited ecosystems due to

both human and natural pressures is increasing

(Valiela et al., 2001; FAO, 2007; Gilman et al.,

2008), thus rapidly altering the composition,

structure and function of these ecosystems and

their ability to provide ecosystem services (Kairo

et al., 2002; Bosire et al., 2008; Duke et al., 2007).

Deforestation rates of between 1-2% per year

have been reported thus precipitating a global

loss of 30-50% of mangrove cover over the last

half century majorly due to overharvesting and

land conversion (Alongi, 2002; Duke et al., 2007;

Giri et al., 2010; Polidoro et al., 2010).

INTRODUCTION

THE ISSUES