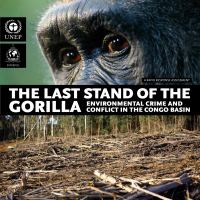

11

Most people think of gorillas as an animal found deep in the tropical rainforests of Africa, as yet

untouched by the modern world; yet the forests are no longer deep, nor are they uninhabited.

Indeed, as conflicts continue in many African gorilla states (UNSC, 2008), the forests are be-

ing cut and burnt to charcoal, timber extracted, roads built, mining operations accelerated and

gorillas, along with chimpanzees, bonobos andmany other species of wildlife, are being hunted

down, killed and sold as bushmeat to feed logging and mining camps and the rapidly rising

population relying on bushmeat (Brashares

et al.

, 2004; Poulsen

et al.

, 2009). A rise is also be-

ing observed along with this poaching and lack of law enforcement in illegal trade and poaching

for other species, including trade of juvenile apes, rhino horn or ivory (Nellemann, pers. obs.).

Gorilla populations are increasingly found in isolated ecologi-

cal islands, frequently in the remaining rugged terrain or in

swamps, facing the continued loss of habitat, lost access to

valuable foraging sites or even capture or death from bushmeat

hunters (UNEP, 2002). Gorillas are also threatened by disease

outbreaks, such as Ebola, and other diseases, some of which can

be transmitted unwittingly by infected tourists and park staff

approaching too close to habituated apes.

In spite of attempts to monitor logging concessions and introduce

certification schemes for timber or minerals, there are currently

no proven schemes in place to secure the continued survival of

gorillas, with the exception of the success of the mountain gorillas

that have been protected by an effective ranger force, supportive

governments and community involvement. Continued road devel-

opment to extract resources also facilitates exploitation of wildlife

for bushmeat (Wilkie

et al.

, 2000; Brashares

et al.

, 2004; Blake

et

al.

, 2008; Brugiere and Magassouba, 2009; Poulsen

et al.

, 2009).

Protected areas currently offer the main formal tool to theoreti-

cally protect the gorillas and many other endangered species.

However, this formal protection depends entirely on the abil-

ity, training and support of the law enforcement agents pres-

ent in the parks, generally in the form of park rangers, some-

times supported by regular police or army units. The price

paid by these courageous defenders of wildlife is high. Con-

fronted with militia making incomes from charcoal and mining

(UNSC, 2001; 2008), widespread corruption and also compa-

nies supported by large multinational networks, more than 200

rangers have been killed in the last decade in the relatively small

area of the Albertine Rift. Poaching to supply bushmeat for

mining, logging and militia camps, as well as towns, is rising

alongside continued habitat destruction and rising human pop-

ulations (Wilkie and Carpenter, 1999; Fa

et al.

, 2000; Brashares

et al.

, 2004; Ryan and Bell, 2005; Poulsen

et al.

, 2009).

The ability of the rangers to enforce laws also depends on other

factors: support from administrative officials, judicial aware-

ness and willingness to prosecute, and not the least, training

and coordination of customs officers and patrolling rangers

(Hilborn

et al.

, 2006).

The Congo basin also holds some the worlds largest remaining

rainforests that provide eco-system services on a global scale

and could play a crucial role in climate mitigation strategies

under the REDD+ programmes. These are being designed to

protect existing carbon stocks and further carbon sequestration

through preservation of rainforests. Establishing appropriate

law enforcement and community engagement is essential for

success and a prerequisite for any REDD+ investment.

This report stresses the urgency of the situation in the Congo Ba-

sin and aims to raise awareness of the success that trans-boundary

law enforcement collaboration can bring even in a conflict region.

INTRODUCTION