116

JCPSLP

Volume 15, Number 3 2013

Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology

with disability in the classroom, two 12-year-old boys, one

with Down syndrome and one with Duchenne muscular

dystrophy. This process involved establishing possible

educational, communication and social goals for these

children, and discussing hypothetical strategies for meeting

those goals together. These cases were drawn from the

resource “Count Us In”

(http://www.disability.wa.gov.au/Global/Publications/Understanding%20disability/

middle%20childhood%20booklet%203.pdf) created to raise

awareness of managing disability in mainstream schools.

eight of her nine speech pathology study participants

felt insufficiently prepared by their university training to

work with low-progress readers in schools, one of a

number of reported barriers to collaborative practice with

teachers. Indeed, despite a growing recognition of the

value of interprofessional education (Barr, Koppel, Reeves,

Hammick & Freeth, 2005), relatively little has been written

about interprofessional learning opportunities between

student speech pathologists and education students. One

case study reported by Peña and Quinn (2003) involved

two student speech-language pathologists working over

an academic year with classroom teachers and their

assistants. The authors describe an evolving process of

team development but note the status imbalance in their

study of using pre-professional speech-language pathology

students with qualified teaching professionals.

Therefore, the rationale behind the study reported in

our paper is that it would be useful to explore issues

around collaborative practice, not only through continuing

professional development but also during undergraduate

training. Davidson, Smith and Stone (2009) report that

interprofessional learning within undergraduate training

promotes a commitment to diversity in practice and is one

way to challenge the persisting idea that interprofessional

work undermines each profession’s knowledge base and

identity. They view interprofessional practice as a core

competency for professionals. Certainly, this reflects the

fourth “range of practice” principle of the Competency-

Based Occupational Standards (SPA, 2011a) which states

that “interprofessional practice is a critical component of

competence for an entry-level speech pathologist”

(p. 9). Likewise, this sort of initiative clearly connects with

Dimension Five of the Competency Framework for Teachers

(WA Department of Education and Training, 2004) “forming

partnerships within the school community”. Davidson et al.

(2009) suggest building on already existing interprofessional

learning opportunities in undergraduate training to expand

and strengthen notions of collaborative teaching and

learning, both within the university and fieldwork settings.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to gather initial

evaluation data on an interprofessional learning opportunity

for both speech pathology and education students at Edith

Cowan University in Western Australia.

Method

Collaborative session

Twelve second-year speech pathology students attended

one of two 3-hour sessions, held over two campuses, with

37 third-year education students (in groups of 20 and 17 in

each site) working towards qualifying as secondary

teachers. These sessions comprised an initial lecture on

inclusion, given by the second author, outlining relevant

theoretical background and legislative underpinnings, and

then tutorials to discuss some of the practical implications

of an inclusion policy for teachers and speech pathologists

in schools (see Table 1, a list developed from the authors’

professional experience in combination with research

findings from, for example, Baxter et al., 2009; Ehren, 2000;

Hartas, 2004; McCartney, 1999). The students then worked

in small interprofessional groups to introduce themselves

and share information about their perceptions of their role

supporting children with special educational and

communication needs in mainstream classes. They also

worked through two video case studies of school students

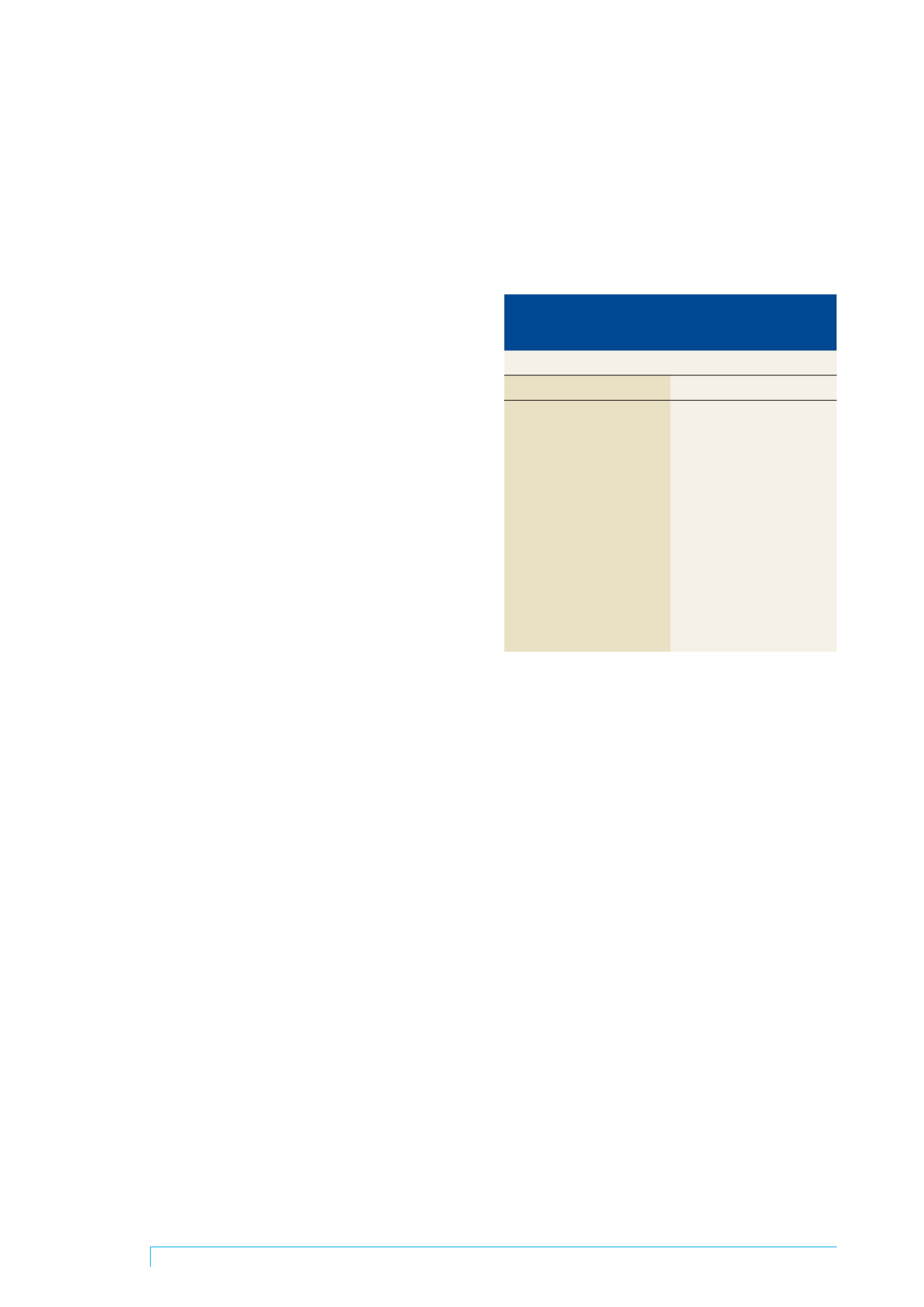

Table 1 Practical discussion points relevant to

collaboration for teachers and speech pathologists

in mainstream schools

Discussion points

Teachers

Speech pathologists

• Time constraints

• Time constraints

• Inflexibility of classroom

• Lack of knowledge of teacher

curricula & timetabling

role and responsibility

• Large class sizes and

• Larger caseloads across

multiple classes

multiple schools

• Multiple children with issues

• Travel required to provide

involving professionals

services

• Lack of support and

• Meeting with teacher in

classroom assistants

DOTT time

• Understanding roles and

• Excessive paperwork

responsibilities

• Dissatisfaction with “pull out”

• Desire to involve other

model

professionals in classroom • Expansion of speech

• Attitude and leadership of

pathology role into literacy

principal

• Resourcing and funding

Logistics and preparation

This was the second year that this interprofessional

opportunity had been run at Edith Cowan University. It

involved a great deal of advanced planning including

timetable switching in order to secure an opportunity for the

two groups of students to meet, and requiring half of the

speech pathology students to travel to a different university

campus for one of the sessions. For the education

students, the topic of collaboration formed an assessable

part of their course whereas for the speech pathology

students, the session was part of a unit covering principles

underlying intervention, including teamwork, collaborative

and interprofessional practice. While highlighted as

important, inclusion in schools was not part of their

assessment for the unit.

Evaluation

As part of the usual practice of evaluating students’

perceptions of the quality of the session, all the students

present were given the option to complete a “3-2-1”

evaluation one week later asking for written comments on

three things they enjoyed about the session, two things

they would change or did not enjoy, and one concrete

suggestion to promote collaboration between teachers and

speech pathologists. The information on the forms was

collated into the three 3-2-1 categories and within each

category, the data was analysed thematically. To do this, all

comments were read carefully and similar comments were

grouped together. The evaluation forms were de-identified

and voluntary and classed by the University Ethics

Committee as a quality assurance process. The students

were aware that this evaluation would be written up for

publication.