2

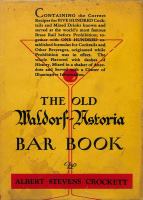

OLD WALDORF-ASTORIA BAR BOOK

together with what was quantitatively described as

"beau–

coup cognac."

When the survivors of the War and its at–

tendant gustatory campaigns got back home, it was to a

country all set for strict Constitutional sobriety, legally en–

forced. America was to be dried up.

Of course, no such thing happened, except in theory.

Sumptuary legislation has always proved repugnant to free

men and difficult to enforce. Instead of becoming alcoholi–

cally arid, the United States grew wetter and wetter as

the years passed. The bootlegger, once among the most

despised members of society, became important-as impor–

tant in his way as the Missing Link might be considered

by ethnologists and anthropologists of the Darwinian

school. Indeed, he proved a missing link. He bought mag–

nificent motor cars or high speed motor boats, amassed

fortunes, grew into might and acquired a definite and

even respectable status as an indispensable member of so–

ciety. More than one read his name in some Social Roster,

-though it had probably been printed there before he

turned outlaw. The racketeer and the gangster, protected

by the politician and even in collusion with the revenue

officer, waxed powerful and became superior to the law.

The average American who wanted liquor bought from

one or the other. What he got was their business, not

his. True, persons with long purses might purchase what

was "good stuff" according to pre-war standards, but mis–

takes were made. The rest of us often paid fancy prices

for labels: Stimulated by the very difficulties created by

the law and encouraged by the ease with which those dif–

ficulties could be surmounted, as well as by the temptation

to break a statute that was never popular in large centers

of population, an appetite for strong drink spread among