www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au

www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au

JCPSLP

Volume 18, Number 3 2016

113

in the research. PRG members sought reassurance from

the primary author that their workplaces would not be

identified in the research, nor would the research require the

participation of clients receiving their services. The criticality

of maintaining the confidentiality of research participants

and of discussing with research participants how their

engagement in the research may impact them was

highlighted here. Further, in international contexts, language

and cultural differences have the potential to impact

understanding of research proposals and outcomes even

when presented in participants’ primary language (Brydon,

2006). A critical role for the PRG was highlighted here as

members guided the primary author through this process

so as to ensure safety in the conduct of the research.

Conclusion

This paper has described three cycles of one phase of a

cross-cultural project in which participatory research

methodology is being used to support international

research in a majority world context. Interviews occurred at

24 months post-graduation to identify the nature of the

graduates’ professional practice, a PRG was established to

guide the future research, and exploration of professional

issues the PRG wished to investigate further was

commenced. The engagement of the SLP graduates and

primary author as co-researchers facilitated mutual

learnings. The vital role of the interpreter as a member of

the research team, the importance of repeated discussion

of concepts to clarify understanding, and the impact of

technology and local context upon communication and

collaboration have been identified. The criticality of

establishing open communication was highlighted in

discussion of ethics and safety in research. Speech-

language pathologists seeking to support service

development in underserved and/or majority world contexts

are encouraged to forge partnerships with international

colleagues that arise from collaboration and support mutual

learnings, for it will be within these contexts that initiatives

may best meet the unique needs of culture and context.

The next cycles in this research are evolving; and, it is

anticipated that further inquiry into the barriers to the

professional practice of SLP in Vietnam and actions to

support this practice will follow. Opportunity will also be

afforded for ongoing exploration of the dynamic of

collaboration between the members of the PRG and

primary author within a cross-cultural context.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors

alone are responsible for the content and writing of this

paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of the

Participatory Research Group to this research. The

contribution of Speech Pathology Australia through its 2014

Higher Degree Student Research Grant, and the support of

the United Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation of Victoria,

Quang Minh Temple, are also acknowledged.

1 The terms “minority world” and “majority world” are frequently

used in the literature to replace phrases such as developed/

underdeveloped countries, North/South, First World/Third World

countries, industrialised/ emerging nations.

2 A further 15 students graduated in 2014.

3 In Vietnam, the profession of SLP is known as speech therapy.

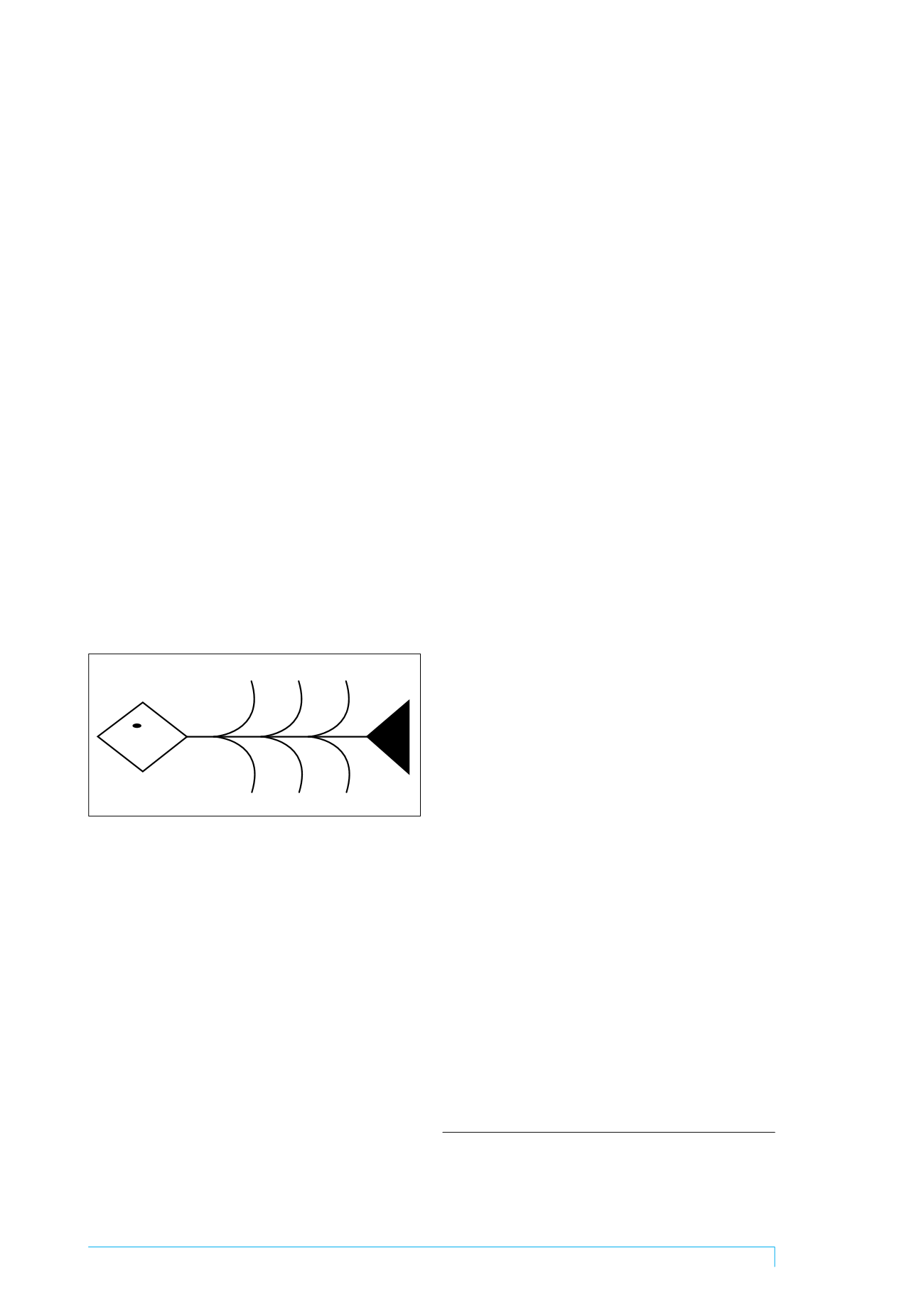

PAR has been described as a “messy process”

(Primavera & Brodsky, 2004), requiring participants to not

only conduct the research, but to learn from it and adapt

as it progresses. The face-to-face meetings were a vehicle

through which to address some of this uncertainty, and

aimed to assist PRG members become more comfortable

about this “messiness”. At one of these meetings, the

PRG developed their own representation of this research

process, which they described as “The fish skeleton”

(Figure 4):

So it [the research] is like a fish bone, a fish skeleton.

So there are different problems and different reasons…

they are the fish bones. The first one is overload [in

work], not enough knowledge [referring to fish bone

number two]. There are many problems and many

reasons and we will look at that to prioritise which

ones, and then we come up with solutions. And then

which solution will resolve number one, number two,

number three…

(Ms Tran summarising)

So you might come up with a solution for a problem

and try it out to see if it works?

(Primary author)

[Discussion between PRG members]

Yes. So they [the PRG] think “participants” defines

it very well what they are doing. Because they are

participating, they are the ones that come up with

these and these and these [referring to the numbered

fish bones], and prioritise these and come up with a

solution. And you are just supporting them.

(Ms Tran

summarising)

1 2 3

4 5 6

Figure 4. The fish skeleton

It was within these discussions that the title of the PRG

was raised. The primary author had previously proposed

that the PRG be referred to as the “Advisory Group”.

However the group indicated that this was not a suitable

term. As summarised by Ms Tran:

For research, “advisory group” is not something that

exists in the Vietnamese research. If you do the literal

translation of advisory group, this means that people

are higher than you are, telling you/advising you what

to do, so that’s not right in the Vietnamese context.

They [PRG members] say they are part of the research,

they are participating. So that describes the role very

well.

The term “participants” was agreed to and the term

Participatory Research Group (PRG) adopted.

Another important outcome from this cycle of the

research was discussion pertaining to issues of ethics in

international research (for further detail regarding ethical

considerations in international research, see Australian

Council for International Development, 2016). Several of

the PRG members reported their workplace directors had

requested information about the role of PRG members