124

125

Chapter 6 / St Edward’s and the Wars

at university and distributed illegal newsheets and British

newspapers, operating hidden radios and upsetting German

communications. In 1943 he was arrested and sent to

Buchenwald Concentration Camp, which he survived, he

thinks, due to his fair hair and blues eyes, admired by the

Nazis as ‘Aryan’. While his treatment was harsh it was not

nearly as bad as for others with him, who were

Jews or

Russians. After a year in the camp he was moved to Hamburg

and then in 1945 to a hospital in Sweden.

An altogether different type of heroism from that of

dangerous missions in the air was the experience of one

young man on the ‘Missing’ list, Sergeant-Pilot Arthur Banks

RAF (E, 1937–42), who in 1945 had not been heard from since

being shot down over Italy in August 1944. He had been in

a Mustang aircraft hit by flak and had made a forced landing,

after which he was seen setting fire to his aircraft. We now

know that local farmers then hid him until he was able to

contact the Italian ‘Boccato’ partisans, which he soon did. For

three months he worked with them in planning and carrying

out actions against the enemy. In December 1944 his group

was betrayed, and captured. He was immediately handed over

to the local German Commander for interrogation.

An OSE, Richard Redmayne Turral (G, 1951–6), wrote a

post-war article about Banks’ dreadful ordeal in the hands

of the Germans and Italians. In the archives is a copy of the

transcript of the trial for war crimes of one German and 20

Italians in March 1946 under the heading of ‘The Torture and

Killing of No. 1607992, Sergeant Banks, RAF, at Mesola and

Adria in December 1944.’ He would give nothing except his

name, rank and number and refused to reveal the names of

the Boccato members that the enemy wanted. He maintained

his silence over six days of increasingly terrible torture. The

Germans handed him over to the Italian Black Brigade,

who continued the torture. He was eventually thrown into

the River Po when his torturers thought him dead, with a

boulder tied to his leg. He managed to free himself from the

boulder and swam for the bank, but it was the wrong bank,

next to the Italian barracks, and he was picked up by the

patrol who had thrown him in the river. An Italian officer

then shot him in the back of his head

and he was buried

in the communal dung heap. Later his body was moved to

Argenta Gap, where men from the Royal East Kent Regiment

(the Buffs) were buried. When the details of this almost

unbelievable story came out he was awarded the George

Cross posthumously.

due to the raid on the Mohne, Eder and Sorpe dams in the

Ruhr. His leadership on the Dambusters raid was outstanding:

his bombing was accurate, and he offered his own aircraft

as a target in order to protect others. By this stage he had

completed over 170 sorties and 600 hours operational flying. In

September 1944 the awful news arrived of Wing Commander

Guy Gibson’s death at the age of 26: he had crashed in

Holland in a Mosquito aircraft with his navigator, having been

the master bomber in a raid on Rheydt. He should not in fact

have been on this sortie at all, as he had already fulfilled his

quota of missions and flying hours, but had requested the Air

Ministry to allow him to continue. Churchill, who had sent

him, early in the war, to America as an air attaché because his

example of what Britain could offer was so impressive, wrote

personally to his widow after his death.

Adrian Warburton (B, 1932–5) was a Wing Commander

with the RAF Reconnaissance Section, a less conspicuous

role than that of fighter pilots, but he was nevertheless a

dashing figure. He appeared to be without fear in his sorties

at extremely low altitude to photograph key enemy ships,

ports and strongpoint installations. He was awarded a DSO

and Bar, DFC and two Bars and the American DFC. He

was a much more swashbuckling character than Gibson or

Bader, being based in Malta, not conforming to rules and

regulations, and frequently appearing accompanied by his

dancer girlfriend. He would return again to targets if an

earlier mission had not produced perfect results. The last time

he was heard from was in April 1944,

and he was believed

to have crashed. In 1945 he was listed as ‘presumed killed’

at the age of 27, just a year older than Gibson

.

The crash site

was not finally discovered until 2003: it was in a Bavarian

field, with his body still in the plane about two metres under

the ground. The plane had flipped over prior to impact

and the propellers had dug out a deep hole in the ground.

He was finally buried two miles from the crash site at the

Durnbach Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery.

A contemporary pointed out that neither Bader, Warburton,

nor Gibson courted popularity or set out to win friends –

which makes their resilience and determination all the more

admirable.

The extraordinary heroism shown by these three tends to

make us forget others. For example, Flying Officer Gordon

Sampson Clear (G, 1926–30) received a DFC for leading his

squadron in an attack on the Molybdenum Plant at Knabon in

Norway. This was a particularly dangerous mission as the target

was hidden in a mountainous area with very treacherous air

currents, but he was successful. He was, very sadly, killed soon

afterwards. There are very many tales to tell of extraordinary

bravery which we unfortunately cannot cover in this book.

An interesting story is that of Theodor Abrahamsen

(D, 1933–9), a Norwegian national who had become Head

of School. He joined the Norwegian resistance while still

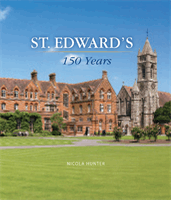

ARTHUR BANKS

The Prosecuting Counsel at the war crimes trial said that‘Men like

Banks,evenhavingsufferedallthathehadsuffered,donotdieeasily.’

HisGeorgeCrosscitationstatedthat‘SergeantBanksendured

much suffering with stoicism, withholding information, which

would have been of vital interest to the enemy. His courage and

endurance were such that they impressed even the captors.’ His

portrait, reproduced here, was painted posthumously by Robert

Swan and now hangs in the Old Library.

Adrian Warburton (B, 1932–5),

centre, in Malta with the USAAF,

April 1943.

Farleft:Painting(byRobertSwan,paintedposthumously)and

medals of Arthur Banks (E, 1937–42). Below is his half sister,

Margaret Castle.

Left: Arthur Banks,

c.

1942.

Of Adrian Warburton

‘A brave and modest

man, serving and

dying with men who

appreciated his worth

to the full.’

–

Chronicle

obituary,

March 1945.