www.stack.net.au

www.stack.net.au

Where did you first get this idea?

DAN GILROY:

A number of years

ago I was very interested in a crime

photographer from the 1930s and ‘40s

named Weegee (the pseudonym for

Ascher Fellig). He’s actually become

collectible among people who collect

photography. He was the first guy to put a

police scanner in his car, in New York City.

This was like 1940. He would drive around

and get to crime scenes before anyone.

He was a wonderful photographer, but I

couldn’t figure out a way to do a period

film, and so I put the idea aside and I

moved to Los Angeles. A few years ago

I heard about these people called ‘night-

crawlers’ who drive around Los Angeles

at night at 100 mph, with these scanners

going. As a screenwriter, I thought, ‘That’s

a really interesting world,’ but I didn’t

exactly know what to do with it. It was part

of an idea. For me, ideas come piecemeal;

they don’t come fully formed. That was

a part of the idea, and I didn’t know what

to do with until I thought of the character

to plug into it, which was Lou. Once that

character plugged into the world, it was like

two parts of an atom that fit together, and

suddenly it just made total sense to me,

and I knew what I wanted to do with the

world and the character.

Did you meet some of the real night-

crawlers?

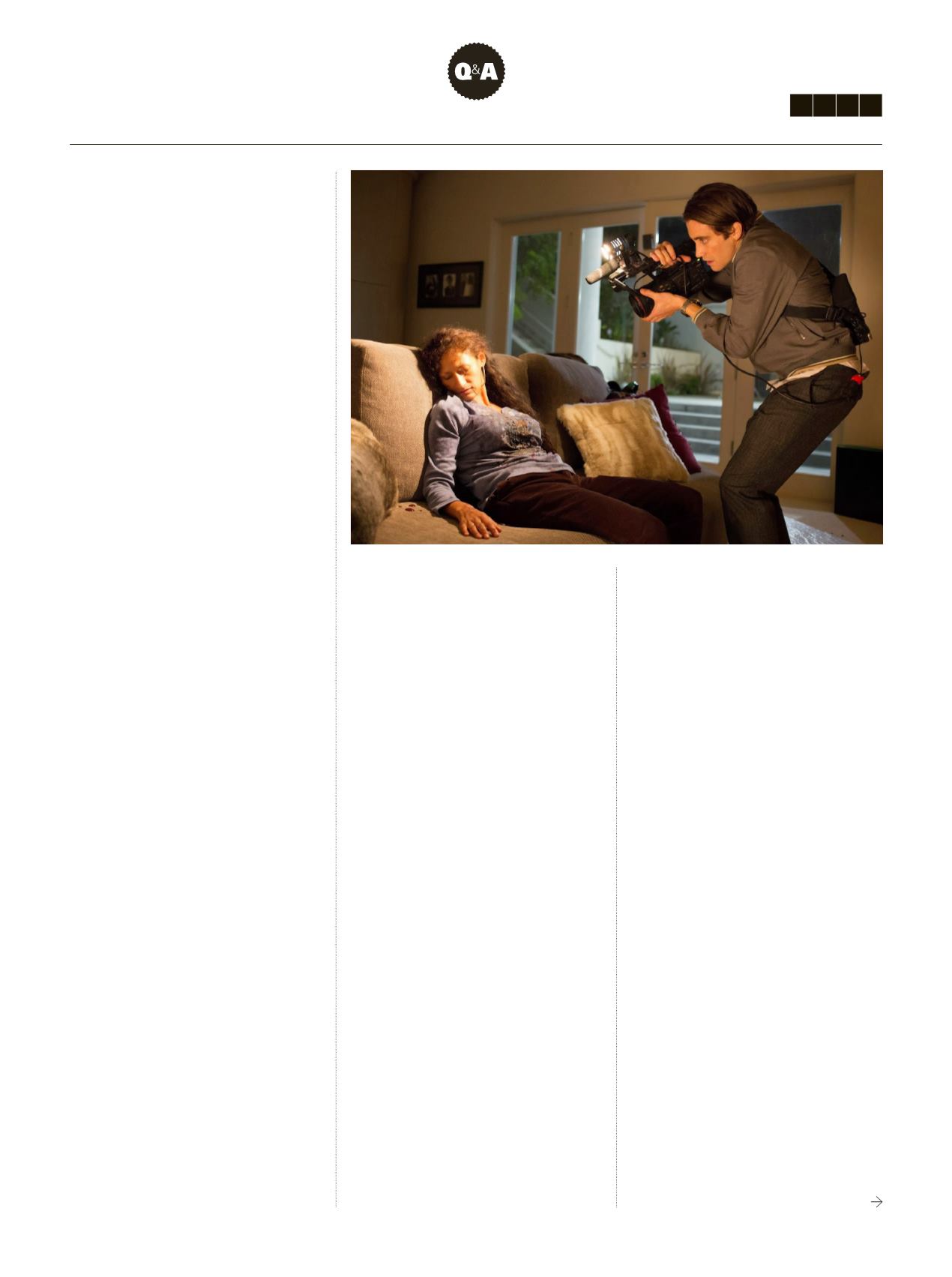

Yes, Jake [Gyllenhaal] and I and Robert

Elswit, our DP, went out a couple of nights

with a guy named Howard Raishbrook,

who was our technical advisor, and it was

bloodcurdling. The first call we went to was

a horrific car crash, in which three girls had

been ejected from a car after hitting a wall

head on. I’ve got to be honest: I don’t think

I’ll ever get that image out of my head. I

think Jake and Robert and I were rather

stunned, watching it, but the gentleman

who filmed it very professionally got out

of the car, shot the footage, edited the

footage within five minutes, downloaded it,

and sold it to four television stations. Now,

the gentleman who does this, I don’t judge

him, and actually he’s become a friend of

mine. He and the other people who do this

very much see themselves as providing a

service, and they legitimately are providing

a service. In their minds, the stories that

they’re filming become the lead stories

on local Los Angeles news, so if there’s a

demand to watch this, who am I to judge

them? Or to say what they’re doing is

wrong? Obviously Lou’s character crosses

the line at certain points, and drifts into a

world that’s amoral, but I never wanted

to portray them or the news media or

even Lou’s character in that way. I never

wanted to put a moral label on it and say,

‘This is wrong.’ I think once a filmmaker

applies immorality to something, it stops

the viewers from being able to make a

decision for themselves. My morality might

be very different from yours, and what I

find important might be different from what

your priorities are. We wanted to create

as realistic a portrayal as possible of this

little niche market and the Los Angeles

media world, and let people decide for

themselves who the villain is and what the

issues are.

Where does the demand for this

coverage come from?

It comes from us because statistically,

as a race, humans seem to like to watch

things that are graphic and gory. It probably

goes back to Neanderthals watching a

lion kill a gazelle, and saying, ‘Oh, there’s

a bloody thing going on over there, that’s

interesting.’ We seem to respond to

watching violence. Maybe not all of us,

but a lot of people do. Look at the dilemma

that Rene [Russo]’s character is in as a

news director. Her ratings are based on

what she shows, and the more blood you

show, the more ratings you’re going to

get. I think my biggest hope, at the end

of the film, is that people might say, ‘I am

one of those people who watches those

things on TV. That doesn’t make me a bad

person, but what does that say about me?

Why am strangely connected with Lou?

Why do I find what he does interesting,

and why am I not walking out of the theatre

at this point? Because what he’s doing is

so reprehensible. We really don’t judge

him, and in fact, we go out of her way to

celebrate what he does, or to legitimise

what he does.

Has your own view on news changed

during the shooting?

No. My view before I started the film

and my view now is the same. I used to

be a journalist. I used to work for

Variety

,

a number of years ago, so I’m interested

in journalism, but I’m aware that in the

United States, a number of decades ago,

networks decided that news departments

had to make a profit, and historically they

did not have to make a profit. I feel that

once news departments are given the

task of making a profit, news becomes

entertainment, and I think we all lose

something enormously important when

that happened because rather than getting

in-depth stories that educate us and inform

us, we get narratives built to sell a product.

The narrative in Los Angeles, and I believe

the narrative you’ll find in most local TV

news, and Michael Moore touched on this

in

Bowling for Columbine

, is a narrative of

fear. It’s a very simple equation: if you’re

not watching the station you’re in peril,

because there are things outside that

could kill you and your family, and if you

don’t watch this, through the commercials,

you’re not going to know about it. It’s

a very powerful formula, and it’s very

effective. That’s what drives the whole

equation.

What should change?

It is such a big problem that there is no

solution to it that I can really see. To be

honest, I would not want to be the person

to put any moral barrier to what could be

shown. My only hope is that we should

be self-aware. As an example, when you

drive down a freeway in Los Angeles and

encounter a traffic jam, and you finally

with

DAN GILROY

2

1

3 4