Eternal India

encyclopedia

MUSIC

RHYTHM

The most important element of Indian

music after the raga is the system of musi-

cal time which is the basis of Indian rhythm.

The rhythm patterns set to different and

complex beats of 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 14 and

16 etc are called

talas.

These correspond to

uniform measure of time. The poetic word-

ings of a vocal rendering are composed within

the frame work of a given'melodic theme and

tala pattern. Thus the raga embodies the very

synthesis of melody, poetry and rhythm.

Indian rhythms are apt to be difficult for

foreigners to grasp. This is because a single

cycle of rhythm or bar can be built out of

units of different duration. The total duration

for the cycle can be divided in various ways.

When the cycles are repeated in the continu-

ous singing or playing, the pattern of accent-

ing may vary even if the total duration of two

rhythm schemes is the same, and the cycle

itself may be long. But one clear punctuation

for the listening ear is available in the first

beat (

sam

) which is the most emphatic of all

the beats in the cycle. The variations by the

singer or solo instrumentalist create drama,

for they tax to the full the alertness and skill

of the accompanying percussionist. The de-

lay creates suspense, and the precision of the

arrival at the same after extended variations

provides an explosive climax.

Indian music has a very complicated tala

structure. This is practically true of Kamatak

music, which has in all 35 talas. This system

was evolved by Purandaradasa (16th C.) prior

to whom there existed an elaborate system of

108 talas.

There is a marked difference in the struc-

ture and treatment of rhythm and tala in the

two forms of Indian music. There is a more

precise and mathematical concept of rhythm

in Kamatak music while a flowing move-

ment is characteristic of Hindustani music. In

Karnatak music the medium . tempo

(,

madhyama

) is precisely twice the speed of

the slow (

vilamba

) and the fast

(drut)

twice

that of the medium. In Hindustani music the

tempo is gradually increased from very slow

to very fast.

To understand the nature of rhythm in

music one has to see how time is divided (in

the first instance) for rhythm is but a particu-

lar arrangement of bits of time. Though time

is measured by breaking it up mentally, we

do use outside adjuncts like clapping hands,

beating together of sticks, striking a mental

plate or playing on a drum. A very common

way of dividing the flow of time familiar to

all of us is the ticking of the clock or clapping

hands. We shall represent such ticks or claps

by

ad infinitum. All the ticks are

uniformly repeated and here we have the

simplest breaking up of the stream of time.

If instead of sounding the ticks in an

identical manner, we clap on only every

fourth and merely count the intervening ticks

without a clap we have -

(a)

123 123 123 123 123

x.. x.. x.. x.. x . . x . . ad

infinitum

Where every x is a clap. Again, we may

arrange the claps in a slightly different pat-

tern thus :

(b)

1 2 1 2 3 1 2 1 2 3 1 2 1 2 3

x . x . . x . x . . x . x . x . .

ad

infinitum

Here, then, are two arrangements, as

they divide time in different ways. In (a)

there.are three counts (one with clap and two

without) for every 'section' which may be

written as a 3+3 pattern. The design in (b)

can be called a 2+3 rhythm.

The series of continuously grouped in-

stants is simply a form of musical rhythm.

This is the kind used in Western music. The

divisions (or bars, as they are known) are

played through in a composition. There is no

further ordering of such groupings.

Indian music takes these bars and creates

the next order. This process leads to the

concept of

tala

which is defined as a recur-

ring arrangement of such patterns.

The essential characteristic of

tala

is its

cyclic or repetitive nature. That is, a set of

rhythmic units are juxtaposed in a cycle and

repeat themselves.

This is easy to understand if we compare

it to the flow of time and recurrence of week

days. Time goes forward in a linear fashion;

but superimposed on this stream are the days

of the week; a Monday, for example,

repeats

itself making the week a cycle. Similarly

musical time flows ahead; superimposed on

it is the tala, each stroke appearing again and

again in the cycle at regular intervals.

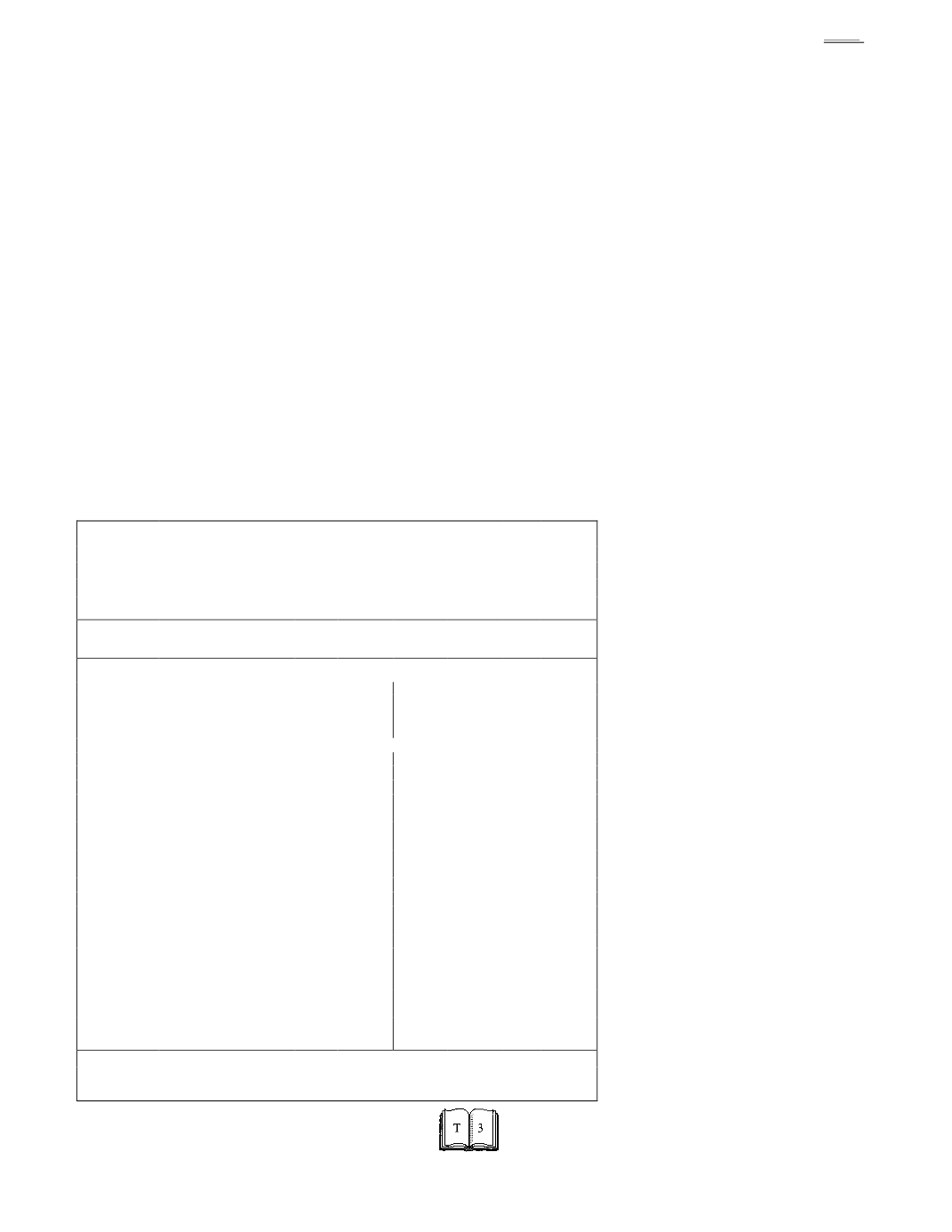

Identification of seven svaras and five interpolated

variants or

vikrita svaras

making up in all twelve notes to

an octave. These have different names

in North Indian

(Hindustani) and South Indian (Kamatak) music,

as listed

below:

Hindustani

Kamatak

Sol-fa

Scale

of C

Tone

Ratio

Sruti

Symbol

Shadja

Shadjam

Doh

C

Sa

Komal rishabh

Suddha rishabham

C#,Db

Major

9/8

4

ri

Suddha rishabh

Chatussrutiri-

shabham

(Suddha gandharam)

Re

D

Ri

Komal gandhar

Sadharana gan-

dharam

D#Eb

Minor

10/9

3

ga

(Shatsruti ri-

shabham)

Suddha gandhar

Antaragan-

dharam

Mi

E —

Suddha madhyam

Suddha

madhyamam

Fa

Semi

16/15

2

Ga

Ma

Teevra Madhyam

Prati madhya-

mam

Maj

F#

9/8

4

ma

Pancham

Panchamam

Sol

G _

4

Pa

Komal dhaivat

Suddha dhaivatam

G#,Ab-

Suddha dhaivat

Chatussruti dhaivatam

(Suddha

dha

nishadam)

La

A

Maj

9/8

4

Dha

Komal nishad

Kaisikhi nisha-

dam(Shatsruti

dhaivatam)

A#,Bb,

ni

Suddha nishad

Kakali nishadam

Ti

B _

Min

'Semi

10/9

16/15

3

2

Ni

(Tara shadja)

(Tara shadjam)

Doh

Cl

Sa'

Note : If all the

shrutis

are added from Sa to Sa they will total up to 22. And if all the ratios are multiplied by one another

they will give a product of 2. This is the measure of an octave or a

Sthayi.