dealer Harry Lunn, gallerists Charles Cowles and Klaus Kertess,

artists Judy Linn and Lynne David, and British heiresses Cather-

ine Guinness and Caterine Milinaire. Diane von Furstenberg

brought the young Arnold Schwarzenegger along.

One chronicler of the age had a particular take on the spec-

tacle: “Fran Lebowitz, then a writer for Andy Warhol’s

Inter-

view

, respected the pursuit of art as something pure and true.

She had known Mapplethorpe as a struggling artist in the back

room of Max’s Kansas City and considered the occasion not as

the beginning of his legitimacy, but as the end: “‘I thought the

party was a joke,’ she said, likening Robert in that context to a

once rebellious girl ‘showing you her big diamond ring and

telling you she’s marrying a rich doctor and moving to Green-

wich, Connecticut.’” Today, Wagstaff and Mapplethorpe might

have cashed in as a cable reality show.

After the sale of his collection to the Getty, and before his

slow withering fromAIDS, Wagstaff moved on to a new area of

collecting and market-building: “æsthetic silver” from England,

the Continent, and the U.S., including serving pieces like cof-

fee pots, butter dishes, napkin rings, a Tiffany tray. Gefter ar-

gues that Wagstaff was moved to recognize early and deeply

these sparkling artisanal works otherwise languishing in the ob-

scurity of the arcane, theorizing that his homosexuality is what

drove his desire to retrieve the “unconventional and unexplored

... to invent a parallel universe of symbols and meanings—such

as camp, for example—in a society that had for so long rejected

his kind.” But we may also wonder if there’s something pecu-

liarly “gay” in this need to acquire and collect anything at all. I

cannot escape the ghoulish sense that all this acquisitiveness

was Wagstaff’s race against time, as if he might escape the final

reckoning since, after all, there was always yet one more object

out there to be admired, studied, and catalogued.

32

The Gay & Lesbian Review

/

WORLDWIDE

T

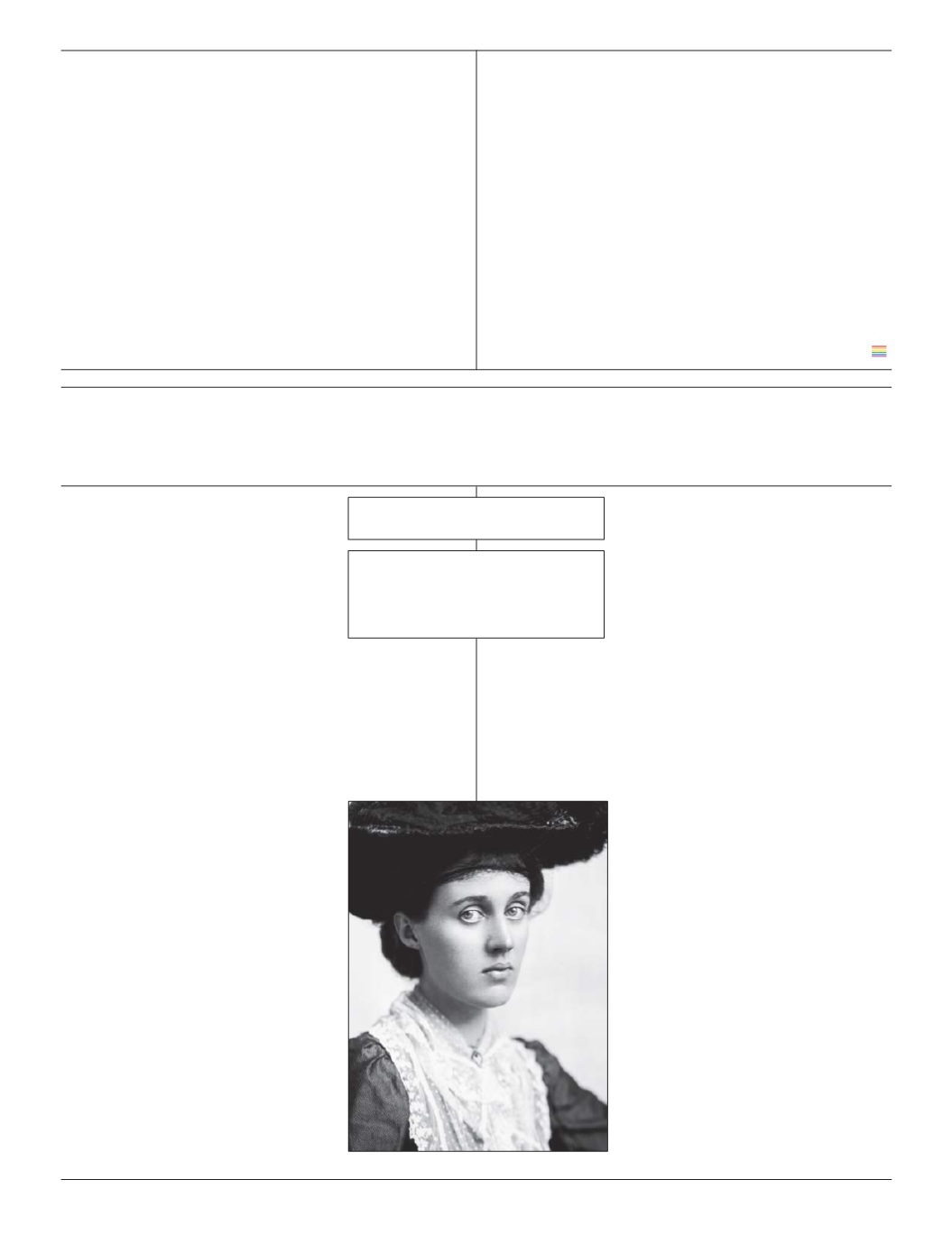

HE DESCENDANTS

of the original

members of the Bloomsbury

Group—a name taken from the

neighborhood in which they

lived, not coined until the 1960s—are very

much among us. Earlier this year,

Van

Gogh: A Power Seething

, by Julian Bell, a

painter and writer who’s the grandson of

Vanessa Bell (and great-nephew of Virginia Woolf), received

front-page coverage in

The New York Times Book Review

.

Vanessa and her younger sister Virginia are the eponymous title

characters of a wonderfully appealing and compulsively read-

able novel by Priya Parmar. It’s told with style and authority by

a writer with just one previous book to her credit, a historical

novel about actress Nell Gwynn.

Parmar’s narrative relies for the most part on an imagined

diary kept by Vanessa Bell from 1905 to

1912. Before her marriage to Clive Bell,

Vanessa had been, in real life, a student of

John Singer Sargent at the Royal Academy

School and an admirer of Whistler’s works.

In an almost throwaway comment on the

pitfalls of fictionalizing such a well-docu-

mented group of people, Parmar writes in

an introductory note: “For me the difficulty

came in finding enough room for invention

in the negative spaces they left behind.” To

say that she channeled Vanessa Bell would

be facile, but her depth of scholarship and

obvious deep regard for the members of the

Bloomsbury Group are apparent.

In 1905, Virginia and Vanessa’s

beloved brother Thoby Stephen, along

with friends he had met at Trinity College,

Cambridge, moved back to London.

Among them were Lytton Strachey, Clive

Bell, and Leonard Woolf. They held

weekly salons to discuss art, literature, and

politics. At first, the sisters were the only

women invited. They would frequently

meet outside their salon, in various per-

mutations, sometimes traveling together,

sometimes forming passionate, platonic—

or even romantic— friendships, regardless

of gender or assumed sexual orientation. Strachey is quoted (in

the fictional diary) as saying: “We all love in triangles.” The

diary frequently veers off into extensive dialog that few diarists

would ever be able to replicate exactly. There’s much tragedy,

too, in Thoby’s 1906 death (from typhoid, contracted in

Greece). “Did you wake up in time to see your last morning?”

Vanessa’s diary entry wondered on the day he died.

Parmar creates tremendous tension around the many emo-

tional illnesses that Virginia Woolf en-

dured: “A few years ago, Virginia talked

for three days without stopping for food or

sleep or a bath. ... [Her] words unraveled

into elemental sounds: quick, gruff, gut-

tural vowels that snapped and broke over

anyone who tried to reach her. Her fea-

tures foxed with anger growing sly and

sharp. ... [She] spent a month in the nurs-

ing home recovering.” Vanessa’s husband,

Clive Bell, and Virginia may or may not

have had an affair. (Strachey was quite

sure there was nothing going on. “It is

your attention she’s after, not his,” he told

Vanessa.) Soon, Vanessa found herself in-

volved with the British artist and critic

Roger Fry, whose wife was permanently

institutionalized for mental illness. Fry,

who “galvanized Bloomsbury,” in the

words of Richard Shone, author of

Art of

Loving in Triangles

M

ARTHA

E. S

TONE

Vanessa and Her Sister

by Priya Parmar

Ballantine Books. 350 pages, $26.

Vanessa Bell, 1910