F E AT U R E S

9

ST EDWARD’S

r

h

u

b

a

r

b

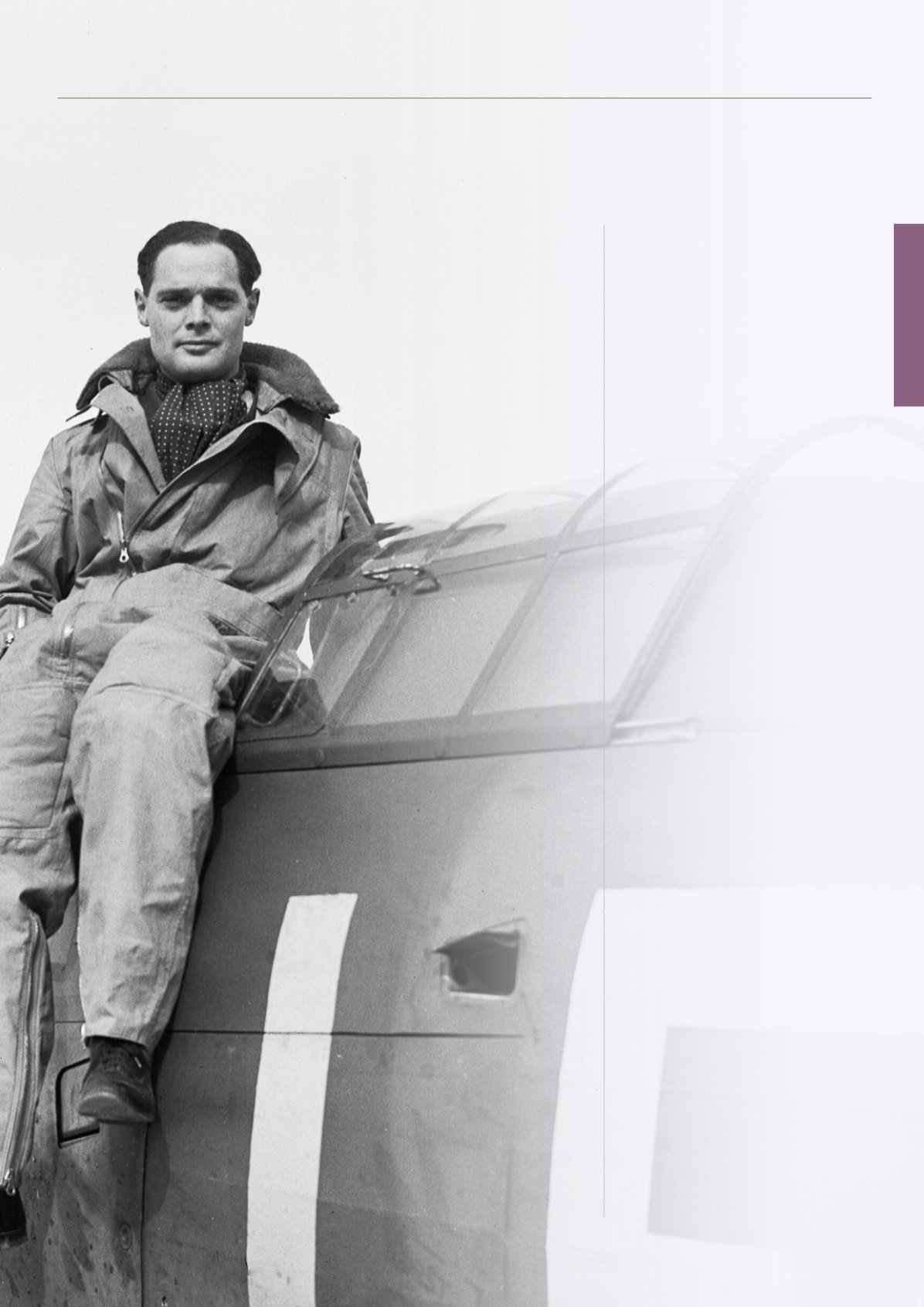

Bader soon wore out the patience of

his German guards at Sagan. Leslie Frith

observed that ‘we lost track of the number

of times we heard a commotion coming

from that direction and there seemed to

be a continual to-ing and fro-ing of heavily

armed guards in the officers’ compound.’

Although admired for his outstanding

and morale-boosting courage, Bader’s

attitude of defiance, which included

baiting the German guards and

other aggressive behaviour, drew

a rather ambivalent response

from his fellow prisoners of

war. This was especially the

case when German retaliation

for some of his activities was extended to

the whole camp while Bader, a celebrity

prisoner, who was often photographed

and given VIP treatment, usually got off

lightly. Collective retribution by the Germans

could include extending the length of the

parades attended by the POWs, delaying

or stopping the distribution of mail and

of Red Cross parcels, which were a vital

supplement to the inadequate camp rations,

and withholding other privileges. Although

the Germans respected him and put up with

a lot more from him than they would from

any other prisoner, the problem was that

Bader sometimes went too far and brought

down their wrath on all the POWs. As a

result, as another RAF prisoner later put it

diplomatically, his continued presence in the

camp did not receive ‘an unalloyed welcome

from all’.

The patience of his German captors finally

snapped in July 1942 and Bader was transferred

from Sagan to a huge camp for British Army

officers at Lamsdorf. As one observer noted

in his diary (IWM, Private Papers of Squadron

Leader C.N.S. Campbell, 86/35/1), ‘the

remainder of the camp annoyed the Germans

exceedingly by turning out to say Cheerio

to Doug and to offer free advice on how to

manage a cripple.’ Some of those who saw him

leave, however, were secretly rather pleased to

see the back of such a disruptive influence. For

example, Leslie Frith later recorded that ‘to tell

the truth it was a relief to everybody, friend and

foe to see him go.’ Many of the prisoners had

rather mixed feelings about Bader; missing him,

yet relieved that they could settle down to a

more relaxed atmosphere in which they could

prepare to escape without the constant risk of

their plans being discovered by the Germans

reacting to Bader’s provocations.

While at Lamsdorf Bader continued to

be active in planning escapes. Sapper John

Andrew remembered in his memoir (IWM,

Private Papers of J J Andrew, 10/5/1) that ‘Bader

wanted to get to Lamsdorf airfield where he

would take a German plane.’ Bader proposed

to take six men with him but although he was

able to escape by joining a work party leaving

the camp he was soon re-captured. Eventually

Bader was again transferred to Colditz Castle in

August 1942 where he remained until liberated

by American forces in April 1945 near the end

of the war, frustrated by his inability to escape

and to participate in the war.