11

ST EDWARD’S

r

h

u

b

a

r

b

F E AT U R E S

There comes a time, usually when forced

to consider subjects to take at A Level, that

the choice of a career starts to edge other -

and more exciting - teenage thoughts aside.

Peter Church (MCR 1950-1987) and Duncan

Williams (MCR 1948-1984) had encouraged

me towards physics and mathematics

which, linked to an RAF family background,

directed my thinking towards engineering

and aircraft. It was then a small step to an

RAF Bursary for the last two years at Teddies

(worth, in 1956, all of £39 per term) and

to transferring from the Army to the RAF

Section for Monday ‘Corps’ afternoons –

different coloured blanco but same hairy

uniforms. Two particular RAF memories from

that time: Douglas Bader taking the Annual

Inspection and the unveiling of the Library

window presented by the Air Force Board.

An RAF Summer Camp at St Mawgan saw

a group of us spend several uncomfortable

and noisy hours in a Shackleton (a maritime

development of the Lancaster) searching for

the replica Mayflower making an Atlantic

crossing and in whose crew was the unlikely

matelot, Jack Scarr (MCR 1942-1980).

After five years at Teddies, it took the

RAF another four years until it considered

me competent to be let loose as a fully-

fledged engineer. One year was spent

as a cadet before taking up a place I had

previously obtained at university (where I

was to come into contact with more OSE

than I did in the subsequent years, although I

had dealings in the RAF with

Tony Leathart

(G, 1958-1962),

Diccon Masterman

(A,

1954-1959),

Robin Scott

(G, 1951-1955),

and

David Pugh

(F, 1947-1952). At that

time (late 1950s), the RAF had expanded

and professionalised the RAF engineering

branch considerably to take account of the

maintenance demands consequent upon

introducing the three new V-bombers (the

Vulcan, Valiant, and Victor), the Canberra,

and a raft of jet fighters (Javelin, Hunter,

Swift, and Lightning). Overall, during my

34 years in the RAF, I reckon the RAF

operated some 54 different types of

aircraft – representing a considerable

design, development, manufacturing, and

maintenance effort. My first tour took me

into the transport world of Britannia and

Comets. There were two versions of the

latter – the stretched and much improved

Mk4 and the Mk2 which was basically the

same as the BEA Comets which suffered

such disastrous fatigue failure, but which

for the RAF had been modified to have

oval, rather than square, windows and

strengthened skin. As for the numbers of

aircraft that the RAF operated in those

days, they seem extraordinarily extravagant

compared with those put into service

now. For instance, 735 Chipmunks (a basic

trainer in which I flew over a hundred

hours with the University Air Squadron)

were delivered between 1949 and 1953.

After the first two tours on transport

aircraft, I was involved with designing a

deceleration device for testing restraint

systems, developing the way the Harrier

could be deployed, management training for

engineering officers, organising deep level

maintenance, and managing the engineering

of the Harrier fleet during the Falklands

conflict - an interesting array of jobs and

more varied than I imagine would be

possible now. And so, after 34 years, it was

into retirement where, much to the dismay

of taxpayers, my ambition is to remain on

the retired list for as long as I was on the

active list – only eight more years to go.

Inevitably, the ethos of the RAF was,

and is, different from that of the other

two military services. Those who engage

in combat do so as individuals, or as part

of a small crew, in aircraft demanding

considerable pilot and other operational

skills, and the majority of non-commissioned

servicemen have to be sufficiently educated

to cope with complex maintenance.

Although there is now a greater involvement

of civilian support both for training and

maintenance – perhaps in detriment to the

‘all of one family’ spirit that pervaded during

my time - the RAF still seeks people with

rather different qualities to those which are

required by the other services. I was pleased

to have had the opportunity to become

acquainted with so many interesting people

connected with aviation, but there is a

regret that I was not bold enough

sixty years ago to ask of those

who had really been bold

“what is the tale behind those

medals?”; I have had to wait

and read the obituaries.

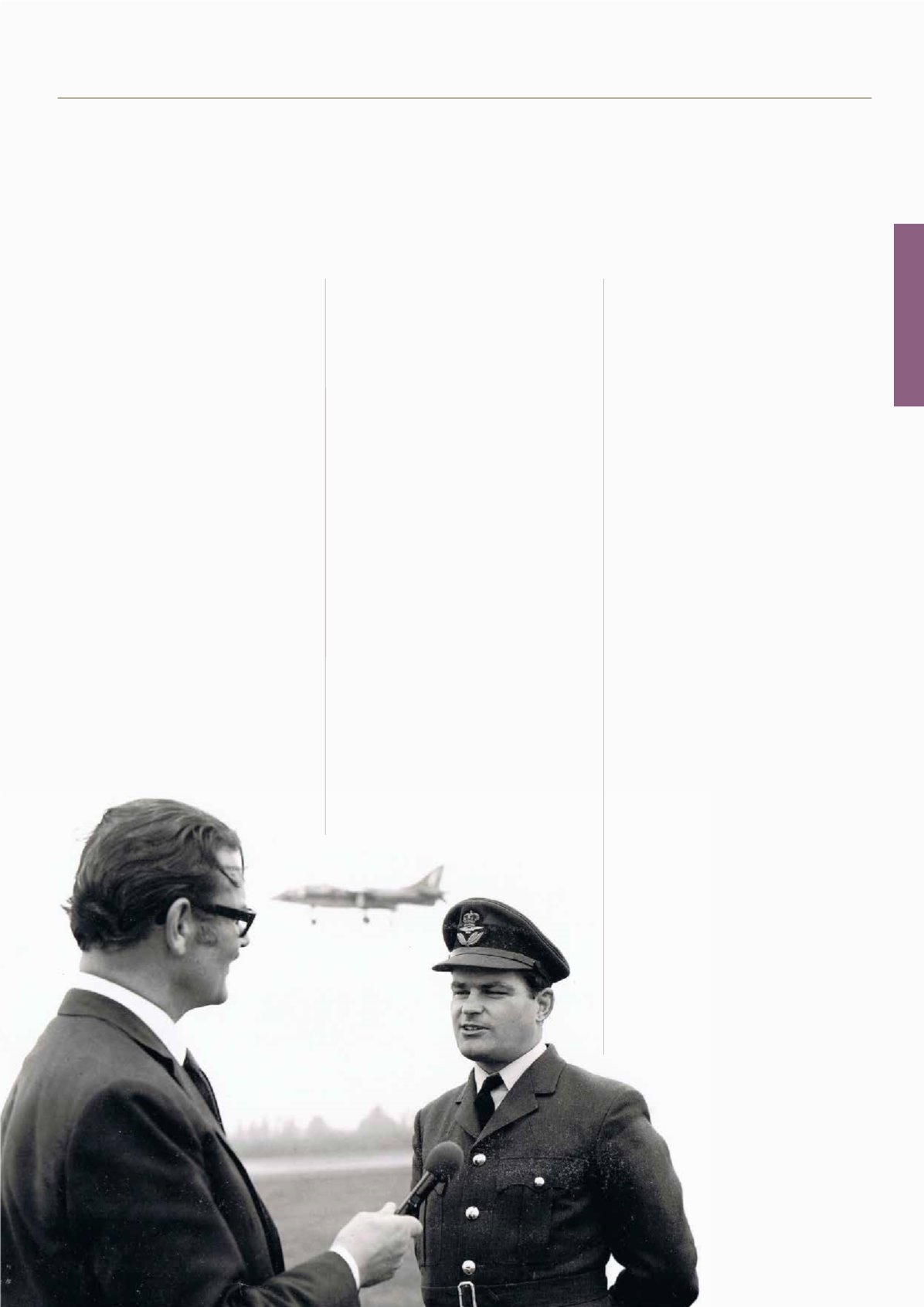

SES to RAF to Retirement

By

Wing Commander Graeme Morgan

(G, 1953-1958)

Wing Commander Graeme Morgan