24

high number of booby traps and mines in the DRC, only a very

small portion of these may affect gorillas, but those placed on

ridges typically can do so, or those near outskirts of fields if

raiding gorillas are common. Snares are also sometimes set

deliberately for gorillas, or more often gorillas are caught in

snares set for other wildlife.

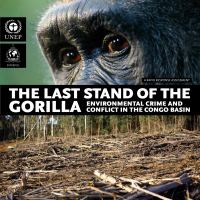

The primary impact of the conflict on gorillas and other wild-

life, however, is not from direct contacts with them, or from

repurcussions as described in the box, but through the exploi-

tation of natural resources and disruption of law enforcement

in the region, as well as the creation of huge refugee camps

in need of fuel. Armed militias, and even regular soldiers, are

used deliberately as escort for trucks transporting minerals,

timber or charcoal across the land Some of these are originat-

ing from protected areas, and transported across borders with

armed escort. Even in instances where border guards are not

bribed, their security is seriously jeopardized if they attempt to

stop the transport.

The killing of gorillas for bushmeat, instances of killing gorillas

as revenge for confiscation of illegal charcoal or law enforce-

ment, or the destruction of gorilla habitat as a result of log-

ging, charcoal, agricultural expansion or mining are among the

primary causes of habitat loss, and eventually, the decline in

eastern gorilla populations.

War and instability also affects conservation resources deriving

from tourism. When the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) moved

into Akagera National Park in October 1990, it resulted in an

immediate drop in tourism and revenues, particularly in the

Virungas, which they partially occupied in 1991. The rugged for-

ested borders of Rwanda, Uganda and the Democratic Repub-

lic of the Congo (DRC) were used as a hide-out and for smug-

gling up until after the Rwandan genocide in 1994 (Kalpers

2001; Rubasha 2008). Then, some two million people – many

linked directly or indirectly to the genocide – fled to Tanzania

and especially to the DRC, mainly settling around the Virunga

National Park, but some in South Kivu. By early 1995, around

at least 720, 000 refugees were living in five camps (Katale, Ka-

hindo, Kibumba, Mugunga and Lac Vert) in the DRC bordering

the park. At least 80,000 refugees moved into the park daily

to collect firewood, and resulted in a deforestation rate of 0.1

km

2

per day, along with that of an emerging charcoal business,

which the CNDP took over when they took control of the park

UNEP’s 2009 report From Conflict to Peacebuilding: The role

of natural resources and the environment identified a major

gap in UN peacekeeping operational planning with regard to

environment-conflict linkages. Since 1990, at least 18 violent

conflicts have been fuelled by the exploitation of natural re-

sources. In situations where environmental issues have the

potential to re-ignite conflict or finance rebel groups, DPKO

operations should begin to consider how natural resource ex-

traction and management can be monitored to support peace

and stabilization.

UNEP’s recent report Protecting the Environment during

Armed Conflict: An Inventory and Analysis of International

Law recommended that the United Nations define “conflict

resources”

*

, articulate triggers for sanctions and monitor

their enforcement. It subsequently advised that the mandate

of peacekeeping operations for monitoring the illegal exploi-

tation and trade of natural resources fuelling conflict as well

as for protecting sensitive areas covered by international en-

vironmental conventions, should be reviewed and expanded

as necessary (on the model of MONUC mandates from UN

Security Council Resolutions 1856 and 1906).

In Resolutions 1856 of December 2008 and 1906 of December

2009, the UN Security Council mandated the United Nations

Mission in DRC (MONUC) to “use its monitoring and inspec-

tion capacities to curtail the provision of support to illegal

armed groups derived from illicit trade in natural resources.”

In 2009, UNEP entered into a technical cooperation with

DPKO/DFS. One of the objectives of this collaboration is to

examine DPKO’s options for improving its operational plan-

ning to address natural resource risks using its existing re-

sources, in particular within the Integrated Mission Planning

Process (IMPP). UNEP together with UNDP will also assess

how the use of natural resources could support Disarmament,

Demobilization and Reintegration processes and create jobs

and livelihood opportunities.

*

UNEP recommends that the United Nations adopt the definition of

“conflict resources” suggested by Global Witness: “Natural resources

whose systematic exploitation and trade in a context of conflict con-

tribute to, benefit from or result in the commission of serious viola-

tions of human rights, violations of international humanitarian law, or

violations amounting to crimes under international law.”