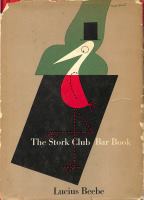

fight at the Stork is today more newsworthy than an atom bomb.

During the second World War the Stork existed in the minds of un–

counted scores of thousands of fighting men all over the world as

the most desirable place in existence. The record is incontestably

available to prove it.

A good deal of highly paid space in coated paper magazines and

elsewhere and the intellectual resources of scores of authorities,

ranging from Stanley Walker and Katharine Brush to the editors

of learned reference books of biography and manners, have been

devoted to evaluating the Stork and Mr. Billingsley and what makes

them click with such astounding and eyer crescent precision. Its

breathless success has been variously attributed to the transcendent

genius of the proprietor, to his lavishness with material favors and

friendship with the reporters, to the Stork's fortunate geographic

location, to its cuisine, to its superb ·disdain for floor shows and

even to the favor and occasional patronage of Mrs. Vanderbilt. The

record, however, will show that the Stork was fantastically profitable

when it was located in Fifty-eighth Street on the wrong side of Fifth

Avenue, that numerous other saloon proprietors have set up drinks

for the paragraphers without any trace of the Stork's overwhelming

prestige, and that Mrs. Vanderbilt also favors with her presence

the Metropolitan Opera, a tradition in no way comparable either

on a fun basis or financially to the Cub Room.

Nor is Mr. Billingsley altogether infallible. Sometimes his most

adroitly fashioned strategies go completely snafu.

Every now and then it is his fond whim to devise a new code of '

signals by which, without attracting the attention of patrons, he

can govern the conduct and the staff of the Stork Club. Recently

he dreamed up a new essay in folly through whose agency he hoped

to inform his doormen and waiter captains of the status and welcome

of arriving guests by a series of code numbers which the m(l$ter

ix: Foreword