66

JCPSLP

Volume 15, Number 2 2013

Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology

•

drawing on existing clinical skills to support the

supervision and education of students.

Learning to be a clinical educator through

reflecting on experience

Key to the learning of participants was reflection on their

experiences as both students and as CEs. As a starting

point CEs reported learning from having been students

themselves. Their own CEs and clinical placements were

the role models and learning opportunities on which these

participants based their own behaviour.

I guess initially your formative sort of influences are

the clinical educators that you had, or that I had, as a

student.

(Beatrice)

And I have really entrenched memories of some of my

clinical educators full of their very, very good style or

their very, very poor style.

(Marie)

The role models to whom the participants referred had both

a positive and negative impact but certainly shaped the

participants’ perceptions of how a CE role should be

performed. This finding is common in the clinical education

literature (Bluff & Holloway, 2008) and is illustrative of how

educators can shape the professional development of the

student through the model they provide (Chivers, 2010).

The participants referred to specific incidents in their own

experience and reflected on how these had shaped them

both as clinicians and later as CEs themselves. There were

often challenging or critical incidents that had had a lasting

impact on the participants:

Horrible memories of it now unfortunately. Five years

on, I can’t believe that these ladies are still impacting

me.

(Paula)

It is notable that the majority of stories centred on negative

experiences that both shook the participants’ confidence at

the time and had a lasting impact on their memories of

being a student. An underlying message was that, as

students, the participants were left perplexed or upset

when they felt things had not been explained to them

clearly and rationally; this they felt undermined their

confidence and their learning. As CEs themselves now, they

asserted that they would act differently in working with

students.

The participants in this study also linked their own

student learning experiences and preferences for learning

explicitly to their current approach to supporting students

themselves:

I felt as a student I learned best when I wasn’t being

watched so I always make sure that I give students

some time on their own with clients to kind of relax

and make their own mistakes rather than always be

watched.

(Aida)

Marie described how as a student she valued a reflector

type approach with her CE that allowed them to discuss

the clients in a way that enabled them to learn together.

Contemporary literature on adult learning in the professional

placement setting recognises the value of both the CE and

student engaging in a learning partnership in which the

student’s contribution is valued (Ryan, 2005).

The practical aspects of being a student on placement

also impact on the learning experience and were identified

as important factors. Participants remembered how tired

An inductive coding process, where codes emerge from the

data (Coffey & Atkinson, 1996), was used in analysis. Initial

coding for each participant’s data noted apparent themes

and subthemes. These themes were then compared to,

and collated with, themes from all interviews. The super-

ordinate themes were then created, re-worked and refined

and examples included from across the whole data corpus.

Thus, a process of analysis and interpretation that worked

both within and across all of the data sets was employed.

In this type of thematic analysis the identification of themes

and their categorisation is used to develop a conceptual

understanding of the experience being explored (Butler-

Kisber, 2010).

Due to the small-scale, interpretative nature of this research,

the findings are not claimed as generalisable and the subjectivity

of the interpretation is acknowledged (Pring, 2000). However,

it is hoped that the reader will find that themes and ideas

discussed here will resonate with their own experiences and

offer a space for critically reflective practice.

What was important to these

ten SLTs learning to be clinical

educators?

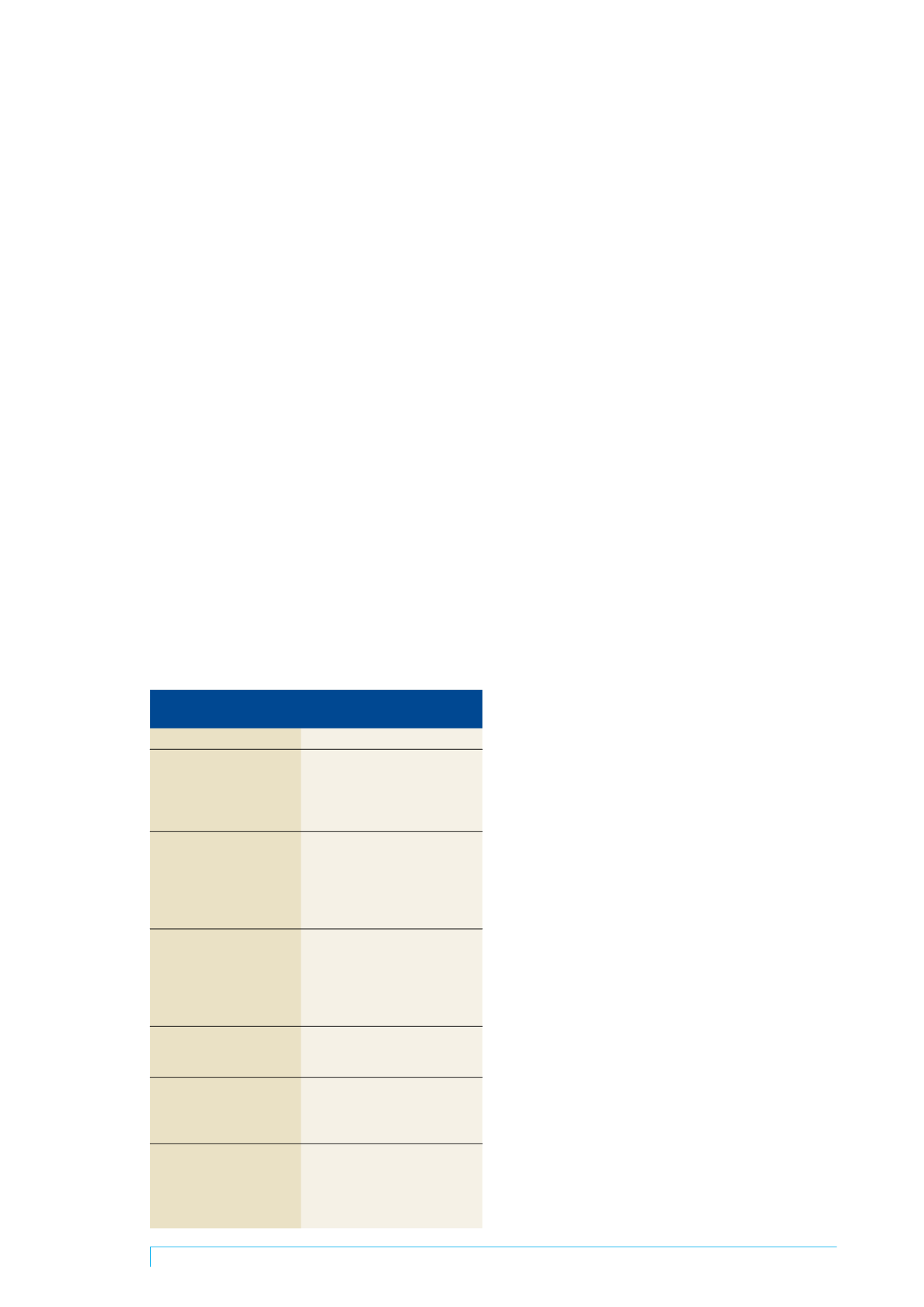

Thematic analysis of the participants’ stories yielded six

over-arching themes, each of which is characterised by a

number of subthemes (Table 2). These themes have been

further distilled for discussion here into three super-ordinate

themes:

•

learning through reflection on their own experiences as

both a student and as a CE

•

a community of practice that offers opportunities for

discussion with, and observation of, colleagues at work

Table 2. Learning to be a clinical educator:

Themes and subthemes identified in the data

Themes

Subthemes

Reflecting on one’s own

Critical incidents

experience as a student

Role models

Learning on placement

Impact on planning as a clinical

educator

Learning and growing through

Critically reflective practice

experiences as a clinical

Feedback from student

educator

“Honing skills”

Learning from challenging

experiences

The clinical context

Drawing on SLT skills

Transferable skills

Being a critically reflective

practitioner

Advanced beginner to professional

artist

Imposter syndrome?

Learning through

Observation of colleagues in the CE

peers/colleagues

role

Peer support

Formal learning

Clinical education training

Post-graduate study/self-directed

learning

Transferable skills

Further growth and role

Lifelong learning

models

Being a clinical educator as CPD

Being a role model as a clinical

educator

Professional artistry/burnout?