6

JCPSLP

Volume 17, Supplement 1, 2015 – Ethical practice in speech pathology

Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology

primarily around the larger contexts in which ethical practice

must be ensured. Speech pathologists at the workshop

spoke of the ethics of a medical emphasis on “saving lives

at all costs”, especially when the costs to quality of life are

high. As a result, allied health professionals increasingly

work with clients with complex disabilities who have care

needs across the lifespan. This in turn impacts on resource

allocation and prioritisation of services, which are already

under strain with population ageing, fiscal constraints and a

shrinking health care workforce.

Workshop participants identified several worrying trends

in resource allocation and prioritisation, including the cutting

of services to some client groups (e.g., those with fluency

or voice disorders, children with speech and/or language

impairments in the absence of concurrent behavioural

problems) and some age groups. For example, in some

states without school-based therapy services, school-aged

children are not a high priority at health services. Further,

service management policies sometimes limit the number of

occasions of service to clients in ways which are not consistent

with evidence-based practice or which may lead to discharge

before an episode of care has achieved the established

goals. As a result, practitioners often experience tension

and conflict between the values of the profession and the

values underpinning management policies (Cross, Leitão &

McAllister, 2008). Such conflicts highlight the needs for

continued work on expanding our evidence base and for

advocacy at individual and professional levels. McLeod,

writing in Body and McAllister (in press), suggests that

reference to the United Nations

Convention on the Rights of

the Child

(1989) and

Rights of Persons with Disabilities

(2006) may provide speech pathologists and their

professional associations with arguments against resource

allocation and prioritisation which exclude children and

people with disabilities from speech pathology services.

It is clear that resources for health care need to undergo

an allocation process; however, how such decisions are

made is an ethical matter. If we want our clients to have

access to a “decent minimum” (Beauchamp & Childress,

2009, p. 260) of health care, then the principles of “equal

share” and “need” can be drawn upon. Allocating resources

on the basis of an equal share for all belies the reality that

some people have more health care needs than others. It

may also result in virtually nobody getting effective care,

“the jam being spread so thinly it can no longer be tasted”

(Sim, 1997, p. 127). The alternative of providing different

levels of health care according to need presents some

challenges as well. A disproportionate amount of service

may be needed to achieve gains, for example, for those

whom we label “disadvantaged”. On the other hand, a

small amount of service may be all that is required to

achieve significant outcomes for some people in so-called

low priority categories. Body and McAllister (in press)

consider the ethics of health economics and provide some

discussion of factors to be considered in making resource

allocations across health services and within speech

pathology services themselves.

One of the outcomes of reducing services available in

the public sector has been the growth of private practice.

While recognising the many benefits of this trend to

both clients and the profession, workshop participants

expressed concern about standards in private practice,

especially with regards to knowledge of the evidence base

and maintenance of fitness for practice. It is worth noting

that a majority of inquiries about possible ethics complaints

received at National Office of Speech Pathology Australia

pertain to service provision within private practice.

By far the largest category of concerns were those related

to resource allocation. These categories are discussed

below.

Discussion

The emerging ethical issues identified in the workshop align

well to the trends presented in the first part of this paper,

particularising these to our professional practice, as well as

raising some new concerns. Of interest in the discussions

at this workshop was the focus on ethical issues at the

systemic level rather than at the individual client–practitioner

level. Inevitably, system level pressures will impact on

services to clients but the discussion in the workshop was

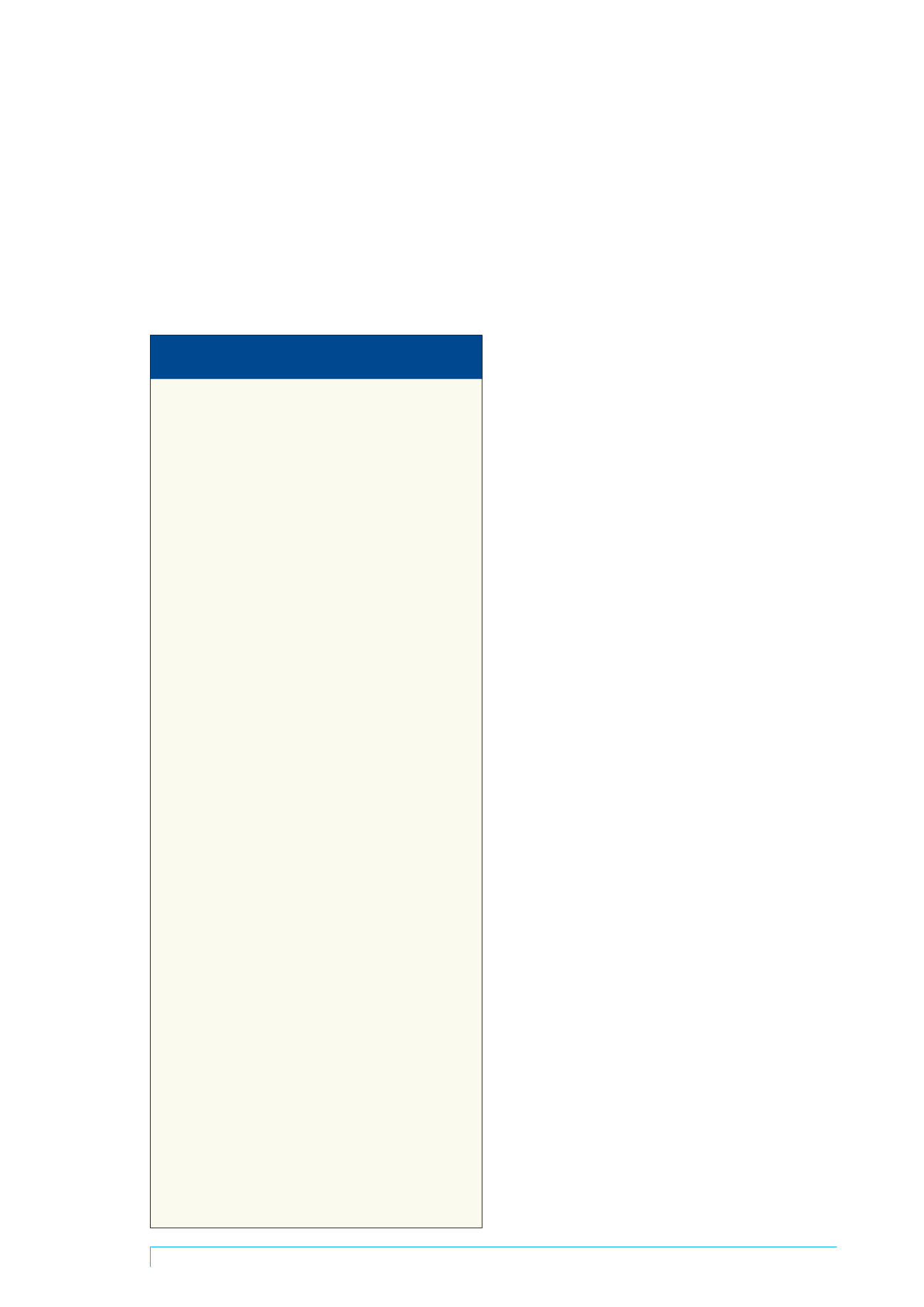

Table 1. Emerging ethical concerns for Australian

speech pathologists

Medical focus on saving lives versus quality of life

Resource allocation and prioritisation issues

• Tension between service policies and values of profession

• Restricting rights of others by focusing on particular service areas

• Narrowing of services to some groups (e.g., fluency, voice)

• Families forced to seek private therapy due to decreased service in

public sector

• Prioritisation – clinician choice versus service direction

• Clients with speech and language alone – low priority compared

with clients with behaviour problems for “early intervention”

• Uneven decision making – acute versus disability

• Tightening of eligibility for service related to age

• How you engage with clients – limitations of service available

• Individual/one-size-fits-all decisions

• Push for discharge versus completion of episode of care

• Time limits imposed not evidence-based practice

• Services to clients of non-English speaking backgrounds especially

in remote areas

Occupational health and safety (OH&S) risk management for

organisation overrides client quality of life

Changing scope of practice

• Consultancy role for speech pathologists

• Expansion of roles in workplace in areas of care planning, advocacy

Use of allied health assistants/support workers

• Training needs

• Clarification of roles

• Accountability to whom? ward? team?

• Safety and risk

Discipline specific versus multi-disciplinary student

placements

Managing expectations of clients

Private practice standards

• Accreditation issues

Evidence based practice

• What evidence? New/old evidence?

• Hard to “manage” the evidence

• Lack of evidence

• Are we ethically bound to research areas with poor/little evidence?

Fitness for practice

• Problems with access to continuing professional development (CPD)

• Supervision re “standards” for rural and remote speech pathologists

• Access to professional development resources and opportunities

restricted by employers (e.g., backfill time not available to go to

CPD; firewalls prevent access to Internet at work)