156

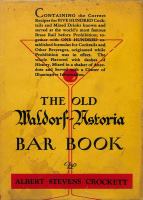

OLD WALDORF-ASTORIA BAR BOOK.

-not necessarily spent before an attack upon the lunch

table-served to keep them in good standing. By such an

outlay as little as three times a week, a man could eat daily

from that hospitable offering a luncheon that, served in

one of the hotel's restaurants, would have set him back a

good two dollars-and get away with it. And many so dici.

The table in the Waldorf-Astoria Bar cost the hotel more

than seventy-five hundred dollars a year. It proved excel–

lent advertisement, for no inconsiderable slice of the

hotel's profits came from the sale of wines and liquors.

Service was rendered with a distinction many establish–

ments of a similar nature lacked. For example, in its early

days, a small, snowy napkin went with each drink, enabling

a patron to remove certain traces from his mustache or his

whiskers-heavy mustaches and whiskers were abundant–

without toting home odors in his hip pocket, or wherever

he carried his handkerchief. And while questions were not

usually asked, men who bought drinks were supposed to be

able to freight them away intact, and not to spill them,

or to show other effects than a certain mellowness and

good fellowship-though perhaps fl:µency in argument or

reminiscence might be forgiven one who was standing

treat.

In

brief, a gentleman was supposed to

be

lar~

than

what he drank. The theory of the proprietor of the estab–

lishment was that all his patrons were gentlemen. And the

theory was good, even if it didn't always work out in

practiGe.

The actual bar itself, a large, rectangular counter at the

northeast corner of the room, as noted, had a brass rail

running alL around its foot. In its center was a long re–

frigerator topped by a snowy cloth and an orderly arrange–

ment of drinking glasses. At one end of this cover stood