Sources: Iman Shebaro,

Hazardous Waste Smuggling: A Study in Environmental Crime

, TRACC website; IMPEL-TFS Threat assessment project:

The illegal shipment of waste among IMPEL member

states

, 2006; Legambiente; The Guardian, 14 October 2004; Human Rights Watch 1999 Report,

Human Rights, Justice and Toxic Waste in Cambodia

; Stockholm International Peace Research Institute,

2006; Small Arms Survey 2005.

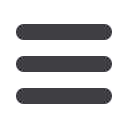

Trafficking waste stories

PLASTIC WASTE

CABLE WASTE

REFRIGERATORS

From Europe

Africa

Eastern

Europe

Asia

CFC PRODUCTS

SCRAPPED CARS

SCRAPPEDCARS

ELECTRONIC WASTE

Nigeria

Côte

d’Ivoire

Somalia

Singapore

Hongkong

Philippines

The 2004 tsunami

washed quantities of

toxic waste barrels

on the Somalian shores.

China

India

Abidjan

Campania

Senegal

Mexico

Baja California

New

Jersey

Mediterranean Sea Red

Sea

States or regions where

illegal waste dumping

has been proven

(not comprehensive)

Major current conflict zones

OECD countries

(main hazardous waste

producers)

Campania

Regions where small arms (related) traffic is particularly developed

Major illegal waste shipment routes from Europe (as reported by IMPEL)

ILLICIT WASTE TRAFFICKING + THE ABIDJAN INCIDENT

Crime industry diversifying

Despite international efforts to halt dumping of illegal waste outrageous in-

cidents occur. Collating relevant data is difficult but there is no doubt about

the damage. Toxic waste causes long-term poisoning of soil and water, af-

fecting people’s health and living conditions, sometimes irreversibly. It main-

ly involves slow processes that must be monitored for years to be detected

and proven (let alone remedied).

Unscrupulous waste trade became a serious concern in the 1980s due to

three converging factors: increasing amounts of hazardous waste; inad-

equate processing plants; and stricter regulations in the developed world

with growing environmental awareness. Managing special waste streams

properly became expensive, apparently too costly for some. Filthy ship-

ments started travelling round the world.

An international answer to global crime

Combating waste trafficking demands international coop-

eration and a high-level of scientific expertise (to analyse

the composition of waste, for instance). This is primarily

the task of customs and port authorities, but initiatives for

broader cooperation are developing, such as the European

Union Network for the Implementation and Enforcement of

Environmental Law (IMPEL), which controls shipments in

major European ports. Waste being shipped is not nec-

essarily hazardous and may consist of scrapped cars, old

fridges, waste plastic (mostly going to Africa) and e-waste

(mostly to Asia).

Fighting against illegal waste trade also requires har-

monised environmental laws and the backing of an inter-

national jurisdiction, regardless of which territories or na-

tionalities may be involved.

Business as usual for (eco)mafia

All the investigations confirm that hazardous waste traffick-

ing is booming. It is mainly the work of existing criminal or-

ganisations, using the same networks and methods as for

other “goods”, such as drugs, arms and people. They some-

times hide behind a legal front in the waste treatment indus-

try. From emission to final disposal this trade involves many

other players, including shipping agents and brokers. On the

way waste may pass through several countries, making it all

the more difficult to pinpoint responsibilities. The prime vic-

tims are developing countries (it is hard to refuse a large sum

when your salary doesn’t cover your living costs) and conflict

zones (trafficking of all sorts thrives on social disorder).

In Italy an estimated 30% of the special waste process-

ing business is thought to be owned by “ecomafia” outfits,

winning contracts quite legally and “taking care” of waste

by dumping it on the Campania Region farmlands or in the

Mediterranean, in Italy and abroad (mainly in Africa). Le-

gambiente, an Italian environmental NGO, estimates that

eco-crime in Italy involves 202 organised groups, with

€22.4 thousand million revenue in 2005. Though profit is

the main incentive, the limited risks are also attractive. En-

vironmental offences are not a priority and police pressure

is consequently lower.

ON THE WEB

Basel Action Network:

www.ban.orgIman Shebaro, Hazardous Waste Smuggling; A Study in Environ-

mental Crime, TRACC:

www.american.edu/traccc/resources/publications/students/she-bar01.pdf