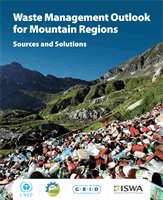

14

growth in recent years in individual countries. For example, from

2000 to 2010 tourism was the fastest growing sector of the

Peruvian economy (Larson and Poudyal, 2012). In the Caucasus,

tourism represents a major part of the Georgian economy and

a significant increase is forecast in its mountainous areas (World

Travel and Tourism Council, 2015).

Mountain tourism includes activities such as trekking and hiking,

climbing or skiing; and in some countries, visiting pilgrimage,

heritage and historical sites. Day trips to mountainous areas are

also common. In many cases, these activities are closely linked

to small and remote mountain communities. Consequently, the

volume and composition of waste being generated in these

communities is often determined by the activities and practices

of businesses in the tourist industry, as well as the behaviour of

tourists themselves (Manfredi et al., 2010; Allison, 2008; Kuniyal,

2005a; Byers, 2014). During the peak tourist season the amount

of waste is sometimes twice as much as the amount generated

during the rest of the year (Manfredi et al., 2010). For example, in

the Sagarmatha National Park and Buffer Zone in the Nepalese

Himalayas, waste generation ranges from 4.6 tons per day during

the peak season to 2 tons per day at other times of the year. In

many small mountain communities waste is inextricably tied to

tourism; any serious waste management solution must therefore

involve the tourism industry (Manfredi et al., 2010).

Systems of waste management in small and

remote mountain communities

Small and remote mountain communities face very specific

challenges to waste management. Poverty is generally more

widespread in mountain regions than in lowland areas (FAO,

2007). Many mountain communities have multiple, pressing

concerns, such as economic development and food security, and

as a result waste management is not given as much importance

(Wilson, 2007). In mountain areas in developing countries, 39 per

cent of people are food insecure, compared to an average of 12.5

per cent in lowland areas (FAO, 2015).

There is little data on the management of waste in small and

remotemountain communities.The few studies available suggest

that formal institutional systems for SWM in remote mountainous

regions in developing countries are largely non-existent. A study

of waste disposal sites in use in 2012 in Nepalese municipalities

found that less than half of the waste in these areas was collected

(Shakya and Taladhar, 2014). One study which focused on waste

management across hill stations, trails and expedition sites in

the Indian Himalayas, found that the relevant authorities, (such

as local municipalities) had no adequate sites, infrastructure or

funds to dispose of the waste generated by visitors. The study

also found that most trekking and expedition areas were outside

municipal boundaries and waste management was entirely

Overflowing waste containers in Uttarkashi (Uttarakhand, India).

Photo

©

Aditi Ramola

Open dumping on a mountain side in Gangotri (Uttarkhand, India).

Photo

©

Aditi Ramola