St Edward’s:

150 Years

Chapter 1 / Origins and Earliest Days

12

13

been described as ‘ascetic, austere, autocratic and unbending’

(R.D. Hill,

A History of St Edward’s School

, 1962), yet he had

a great passion for educating children. St Edward’s was one

of several schools he opened and, luckily for those who have

since benefited from their education here, the most successful –

indeed, the only one actually to survive. He left the day-to-day

running of these schools to others, and in New Inn Hall Street

he charged one of his curates with this task, the Revd Frederick

Wilton Fryer MA, who became the first of three Headmasters of

the School. Chamberlain named it the School of St Edward, King

and Martyr, for reasons which he did not record, and the new

School’s religious services were of course held in his own church,

St Thomas’s. The role of Warden in the School did not come into

being until after the move to Summertown.

The School premises were less than desirable by modern

standards. They were part of what had once been a fine

property owned by Lady Mackworth, known as Mackworth

House, but had become badly dilapidated by the time the

School was set up. Kenneth Grahame, the world-famous author

of

The Wind in the Willows

, who was a boy at the School in

New Inn Hall Street, dated it ‘at about Queen Anne’. There

were many rats which apparently ‘swarmed under the floors,

in the walls and over the rotten rafters’ (Hill), the structure

itself was not in good order and hygiene was very basic, with

bathing in moveable tubs which were brought before an open

fire in winter and abandoned altogether if the weather was

too cold to draw water. Lighting was by candle. One of the

upstairs rooms was used as an Oratory. There was a gravelled

playground at the back for exercise and the boys also played

some games in fields and open spaces in the locality.

There were two storeys into which classrooms,

dormitories and kitchens were squeezed. Teachers sometimes

had to sleep in cupboards (so the next Headmaster, Simeon,

said), and space was clearly at a premium. The teaching staff

consisted mostly of Oxford undergraduates fitting in teaching

round their studies. From a start with just two pupils in 1863,

in 1864 the numbers reached 22, in 1865 there were 34 and

by 1866 there were 49. Ages ranged from eight to 18. The

academic curriculum was circumscribed and consisted of

‘Repetitions in Latin, Greek and Latin accidence’. Irton Smith

(Roll 97) complained that no attempt was made to explain

why Greek and Latin should be learnt, while Literature was

Right: The first Headmaster, Revd Frederick Wilton Fryer MA,

c.

1870.

Farright:AlgernonBarringtonSimeon

c.

1865.Hebecamethesecond

Headmaster in 1870 and later Warden in 1877, with the post of

Headmaster (later to be SubWarden) beneath him. It was he who

owned the School by the time it moved.

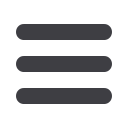

School population 1870. This was

Algernon Barrington Simeon’s first

term as a teacher at St Edward’s and

the year he became Headmaster.

Simeon in centre, A.H. Chesshire to

Simeon’s right in light jacket, W.H.

LeedsisonSimeon’simmediateright

in cap, D.F. Lewis on Leeds’s right.

K. Grahame is at Simeon’s feet. The

other teacher shown is A.T.C. Cowie.

Kenneth Grahame on the use of the cane inNew

Inn Hall Street:

‘The lowest class, or form, was in session,

and I was modestly lurking in the lower end of it,

wonderingwhat the deuce it was all about, when

enter the headmaster. He did not waste words.

Turning to the master in charge of us, he merely

said:“Ifthat”(indicatingmyshrinkingfigure)“isnot

up there”(pointing to the upper strata)“by the

end of the lesson, he is to be caned.”Then like a

blast away he passed, and noman sawhimmore.

Here was an affair! I was young and tender,

well-meaning, not used to being clubbed and

assaulted; yet here I was, about to be savaged by big, beefy, hefty,

hairy men, called masters! Small wonder that I dissolved into

briny tears. It was the correct card to play in

any case, but my emotion was genuine. Yet

what happened? Not a glance, not a word was

exchanged; but my gallant comrades, one and

all, displayed an ignorance, a stupidity, which

even for them, seemed to me unnatural. I rose,

I soared, till, dazed and giddy, I stood at the very

top of the class; and there my noble-hearted

colleagues insisted on keeping me until the

period was past, when I was at last allowed to

descend from that “bad eminence” to which

merit had certainly never raised me. What

maggot had tickled thebrainof theheadmaster

on that occasion I never found out. Schoolmasters never explain,

never retract, never apologise.’

KENNETH GRAHAME

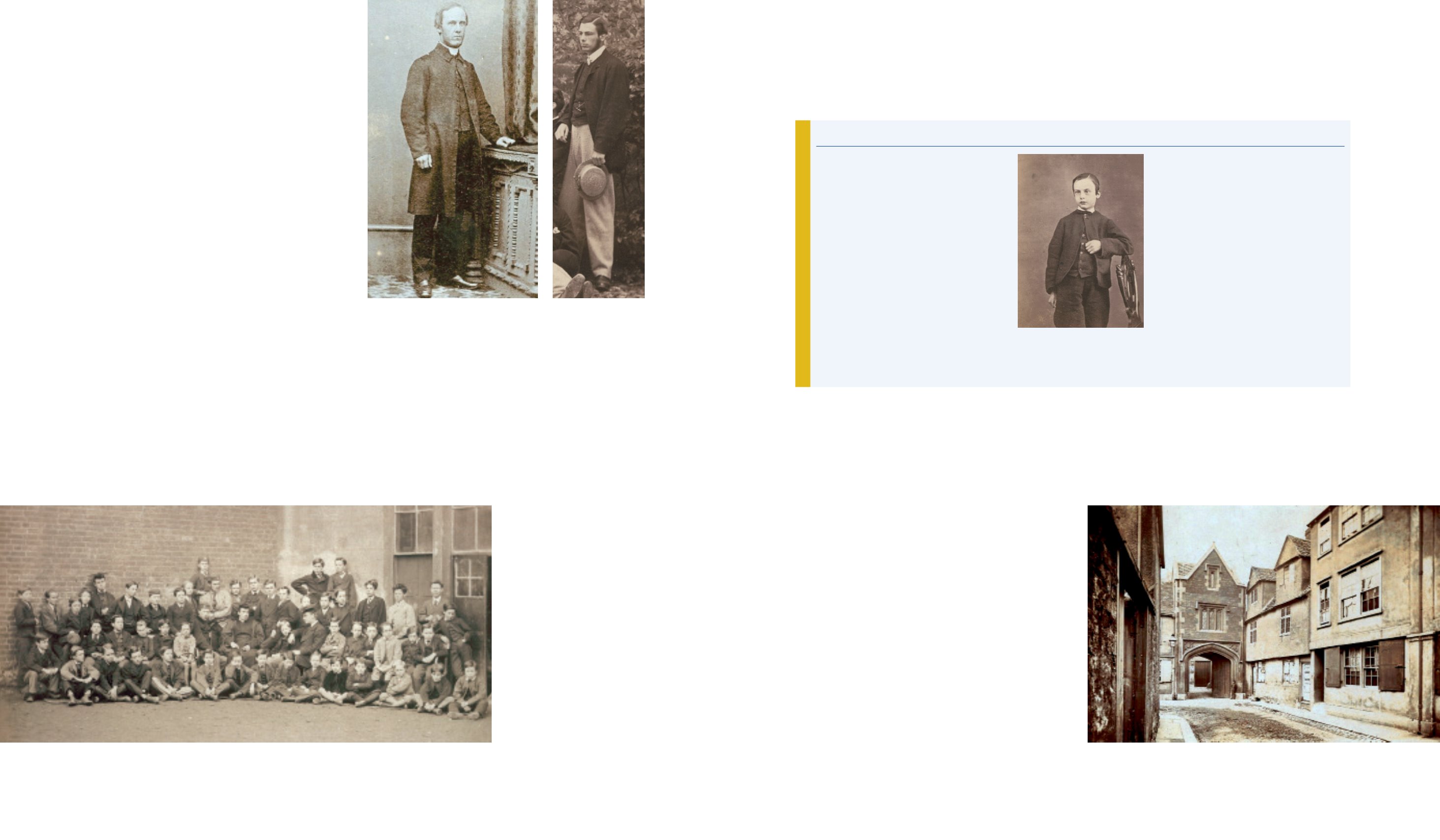

‘A hundred years ago, this street, cobbled for its

entirety, and earlier known as Seven Deadly Sins

Lane, did not run north for its full

length.Atthe

junction with what is now St Michael’s Street, a twin-

gabled house barred its further progress and it swept

round at right angles to run out as it does today, in

the Corn[market].The whole was named New Inn Hall

Street, from the now defunct Hall which was once part

of the

University.Onthe corner, but with forty-eight

feet of its frontage to the west, was No. 29, a stone-built

house which had earlier enjoyed the grandiose title of

Mackworth House, the residence of Lady Mackworth.’

– R.D. Hill

Henry Taunt’s photograph of New Inn Hall Street, 1865.

Entrance to School playground shown on left.