Supporting social, emotional and mental health and well-being: Roles of speech-language pathologists

www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.auJCPSLP

Volume 19, Number 3 2017

125

KEYWORDS

BEHAVIOUR

LANGUAGE

LITERACY

PROFESSIONAL

COLLABORATION

SEBD

THIS ARTICLE

HAS BEEN

PEER-

REVIEWED

Hannah Stark

primary school-aged students with SEBD (including an

overview of current provisions), and the issues associated

with the identification and remediation of language and

literacy difficulties in this population. Second, clinical

insights, including a description of current educational

provisions, and a rationale behind the delivery of a speech

pathology service for this student population is offered.

This is followed by the author’s reflections upon the early

implementation of a service within a specialist school for

students with SEBD.

Review of the literature

Conceptualising classroom behaviour

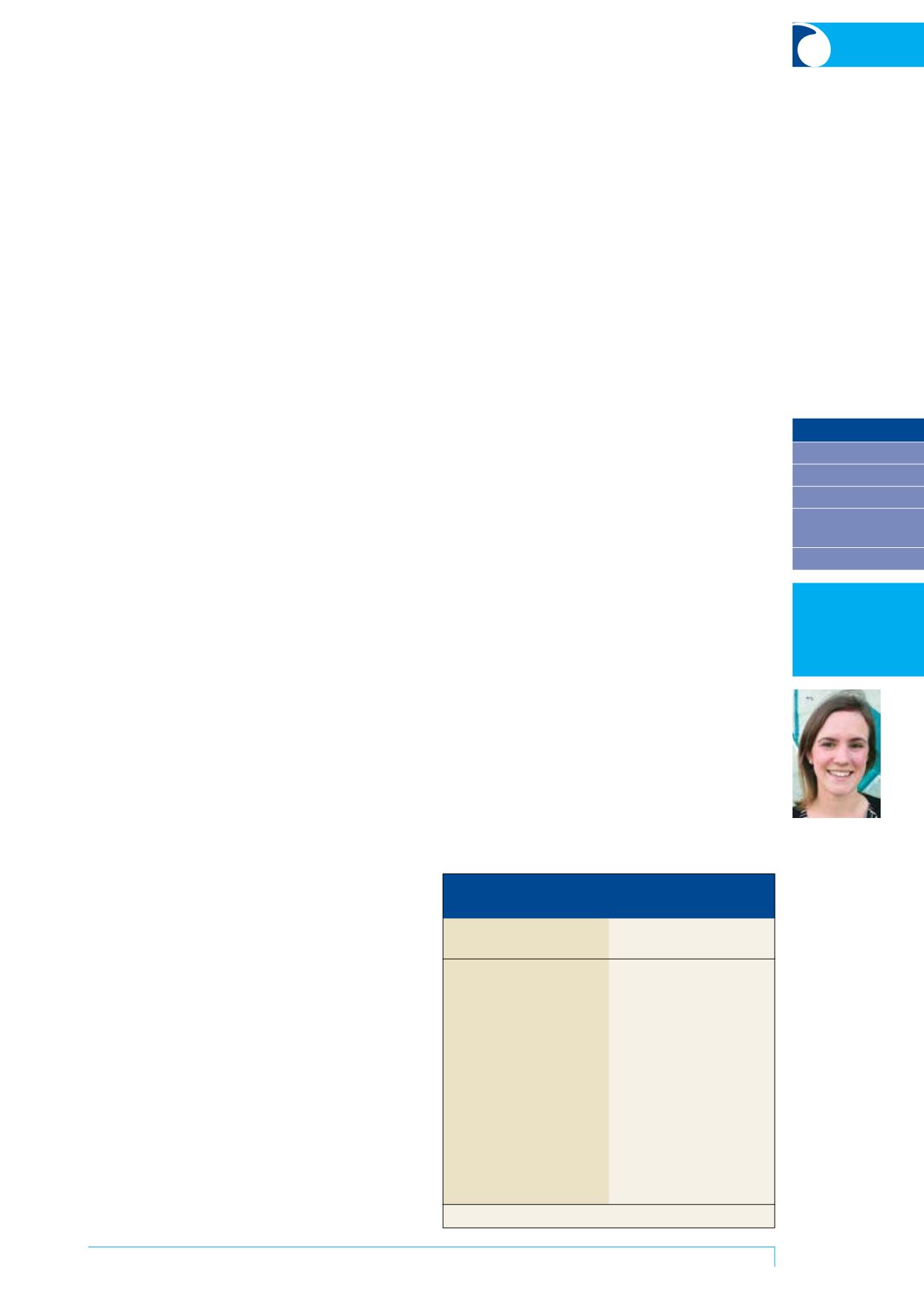

The affective states of students, such as increased anger,

anxiety, emotional lability, depressed mood, signs of

trauma, a lack of empathy or an inability to cope, and their

associated behavioural manifestations, can present

challenges to teachers and SLPs within classroom or

clinical settings (Cross, 2011; Todis, Severson, & Walker,

1990). These associated behavioural manifestations may be

externalising (for example, aggression towards peers) and/

or internalising (for example, the avoidance of peers) (see

Table 1), and it is important to note that these behaviour

types are not mutually exclusive (Todis et al., 1990).

Disruptive or unproductive behaviours in the classroom are

limited only by a student’s imagination, but commonly

While the adage “behaviour is

communication” is frequently used in speech-

language pathology practice, the interactions

between communication and behaviour are

often poorly understood in practice in

Australian primary schools. This article will

provide an overview of how classroom

behaviour is conceptualised including

existing literature about the communication

profiles and needs of primary school students

with social, emotional and behavioural

difficulties (SEBD). Current education

provisions for these students will also be

discussed. Clinical insights from a pilot trial

of a speech-language pathology program in a

specialist unit for primary school age children

with SEBD will be offered, along with

recommendations for speech-language

pathologists (SLPs) who assess, support and

advocate for this population.

P

rimary school age students with social, emotional

and behavioural difficulties (SEBD) are a cause of

great concern to teachers and school administrators

(Armstrong, Elliott, Hallett, & Hallett, 2016; Graham, Sweller,

& Van Bergen, 2010; Stringer & Lozano, 2007; Tommerdahl

& Semingson, 2013; Van Bergen, Graham, Sweller, & Dodd,

2015). Even though most speech-language pathologists

(SLPs) who work in primary school settings will have

students in their caseload who present with behavioural

difficulties, it is suggested that, for a number of reasons,

speech-language pathology services are not sufficiently

accessible to vulnerable students, including those with

SEBD (Cross, 2011; Hollo, Wehby, & Oliver, 2014; Snow,

Powell, & Sanger, 2012; Stringer & Lozano, 2007). The

Speech Pathology Australia

Speech Pathology Services in

Schools

Clinical Guidelines (2011) recommend “that SLPs

working in schools continue to advocate for involvement in

less well recognised fields such as behaviour management,

mental health” (p. 21). Six years on, involvement of SLPs in

the support of students with SEBD in schools continues to

be an emerging area of practice in Australia.

This article first provides an overview of the literature,

including the conceptualisation of problematic classroom

behaviour, the prevalence and communication profiles of

The role of the speech-language

pathologist in supporting primary

school students with social, emotional

and behavioural difficulties

Clinical insights

Hannah Stark

Externalising classroom

behaviours

Aggressive behaviour towards

objects or persons

Arguing

Forcing the submission of others

Defying the teacher

Being out of the seat

Not complying with teacher

instructions or directives

Having tantrums

Being hyperactive

Disturbing others

Stealing

Refusing to follow teacher or

school imposed rules

Table 1. Examples of externalising and internalising

classroom behaviours

Internalising classroom

behaviours

Low or restricted activity levels

Not talking with other children

Shyness

Timidity or unassertiveness

Avoidance or withdrawal from

social situations

Preference to play or spend time

along

Fearful behaviour

Avoidance of games and

activities

Unresponsiveness to social

initiations by others

Not standing up for oneself

Source: Todis et al., 1990