www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au

www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au

JCPSLP

Volume 17, Number 3 2015

115

family’s adjustment, implement recommendations, and

monitor the child’s progress” (p. 13). Therefore, this small

study aimed to gain an initial understanding of parental

(specifically mothers’) experiences of discharge from

hospital, transition from hospital to home with a baby with

feeding issues, and the role of SLP in that discharge and

transition.

Method

This research study used thematic analysis, which allowed

a detailed exploration of individuals’ first-hand experiences

(Creswell, 2007; Liamputtong, 2009). In-depth, semi-

structured interviews (Corbin & Morse, 2003) were used

with three of the participants and two email-based

interviews with a fourth participant. The interviews explored

how mothers experienced the time leading up to their

children’s hospital discharge, the transition home, and the

role of SLP.

Participants

Four mothers of babies with feeding issues were recruited

at a children’s hospital in Western Australia. Three were

biological mothers and one was a foster mother. These

participants were identified by their SLPs, and were then

invited to participate in the study. To be eligible to

participate, the baby had to (a) be under one year of age,

but beyond the neonatal period; (b) have feeding issues,

and (c) be admitted as an inpatient. However, it was not a

requirement that the feeding issues were the cause of the

hospitalisation. Participants were offered the opportunity for

an interview within a few days before discharge and another

up to a month post discharge. However, two mothers (Mel

and Renee) elected for a single interview at discharge, citing

time constraints, and another (Charlotte) decided to be

interviewed via email over two occasions. The research

study received approval from both the Edith Cowan

University Human Research Ethics Committee and the

Princess Margaret Hospital. The details of the participants

are provided in Table 1. All names used are pseudonyms.

Conduct of the research

During the data collection period of three months, six points

of contact were made with the four participants – four

interviews were completed face-to-face, and two by email.

The topic guide for the first interview covered feelings

around discharge readiness, anticipation of going home,

and involvement of SLP including its influence on

management of the child’s feeding. The second interview

involved revisiting the same issues but from a post-

discharge perspective.

of health disciplines are typically involved in the health care

team. This team includes SLPs who are experts in feeding

and swallowing disorders, and have a role in assessment,

treatment, and ongoing support of these children and

their families (Bell & Sheckman Alper, 2007; Carr Swift &

Scholten, 2009; Cichero & Murdoch, 2006; Mathisen et

al., 2012; Miller, 2011). Indeed, the adoption of a family-

centred approach to the management and care of babies

and children with feeding difficulties is well accepted as

good practice in SLP (Mathisen, 2009). However, relatively

little research has, as yet, been carried out in relation to

the families of this group of children. As Mathisen wrote:

“Surprisingly, the particular experiences and concerns of

families of infants and children with dysphagia have not

been thoroughly investigated or reported” (p. 253). Indeed,

even less research is available exploring the experiences

of parents of this group of children at discharge from

hospital or transition between services. An exception is

a qualitative study of the experiences of nine parents of

children with feeding difficulties in a neonatal unit (Carr

Swift & Scholten, 2009). While the participants in this study

talked about a range of issues within the unit, including

feeding interventions, bonding between parents and baby,

and family strain related to juggling commitments in and out

of hospital, a key finding was the strong desire to get home.

Discharge decisions were closely related to feeding and

gaining weight: “the feeding interaction became focussed

on intake, to get the baby home” (p. 253) which led to

considerable parental frustration. This research hinted at the

centrality of discharge issues for this group of parents but it

did not explore the role of SLP.

Conversely, Mathisen and colleagues (2012) presented

evidence for SLPs to have a core role in neonatal intensive

care units but do not discuss this in relation to discharge

issues. In fact, to the authors’ knowledge, no studies

have been conducted to examine parental experiences

and the role of SLP leading up to, and at the time of,

discharge for babies or children with feeding difficulties.

This gap exists not because this issue is not important, but

perhaps because the SLP role is subsumed into that of

the team, or because SLP research generally has tended

to focus attention on assessment and intervention and

give less recognition to discharge or transition (Hersh,

2010). However, a recent clinical report (VanDahm, 2010)

highlighted the roles of both acute and community SLPs

in assisting families of these children and specifically noted

the importance of the SLP in the transition from hospital to

home for these children and families: “SLPs play a critical

role in working with these children and their families before

and after discharge from acute care as they support the

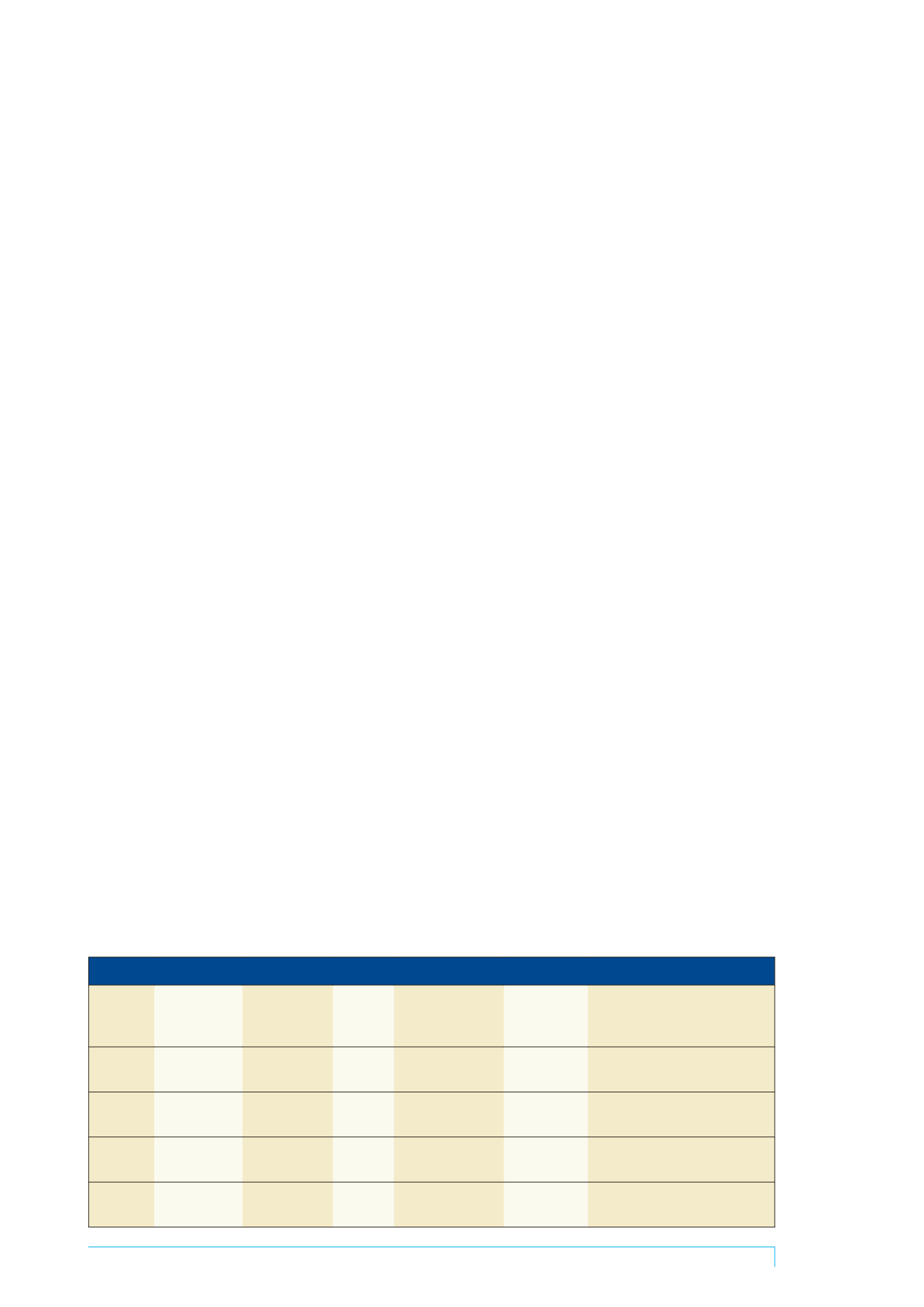

Table 1. A summary of participants’ social and medical circumstances

Mother

Marital status Baby’s gender

& age at

interview

Baby’s

siblings

Baby’s medical

issue

Hospital stay

length

Primary feeding method

Tia

(28 years)

Married

M 10 months

1 (twin)

Tetralogy of fallot

and cardiac surgery

2 months (in

and out)

Transition from nasogastric tube

to bottle

Mel

(29 years)

Married (foster

mother)

M 7 months

3 (foster

children)

Foetal alcohol

syndrome

1 week

Bottle-feeding

Renee

(26 years)

Married

F 10 months

No other

children

Cardiomyopathy

1 month

Bottle-feeding

Charlotte

(27 years)

Married

M 5 months

2

Prematurity, atrial

septal defect

2 weeks

Nasogastric tube