122

JCPSLP

Volume 17, Number 3 2015

Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology

of M-SLI’s utterances. In terms of some of the subtypes

of OT utterances, “comprehension monitoring” accounted

for 18.4% of all of M-ASD’s utterances, and 1.1% of all of

M-SLI’s utterances. Both M-ASD and M-SLI used a similar

proportion of OT utterances in the form of “praise” (8.2%

and 8.0% of all of their utterances, respectively).

Discussion

In this study we explored the characteristics of naturalistic

mother–child interactions during SR when a child had been

diagnosed with ASD or with SLI. Across the entire

interaction, M-ASD used more OT utterances compared to

EC utterances. OT utterances were defined as praise,

comprehension monitoring, and referring to images. This is

evident, for example, when she pointed to a picture during

the SR and explained “…bursting into flames. See, all the

bush here is on fire and the trees have burst into flames”. In

contrast, M-SLI demonstrated a clear preference for EC

utterances which pertained to providing the correct word,

sounding out (e.g., “Stay-di-um, stadium”), and

encouraging correction (e.g., “No, not ‘tried’, say it again”).

With regard to subtypes, M-ASD appeared to focus

more on OT utterances in the subtype of “comprehension

monitoring” compared to M-SLI. Previous research

suggests that some children with ASD experience particular

difficulties with reading comprehension (Arciuli, Stevens, et

al., 2013; El Zein et al., 2014; Nation et al., 2006). Although

C-ASD scored above average during standardised testing,

he appeared to exhibit a relative weakness with reading

comprehension in terms of reading the book we selected

for the current study. This was reflected in the proportion

of comprehension monitoring utterances used by his

mother in their interaction. By contrast, M-SLI had a

higher proportion of EC utterances in the subcategory of

“providing the correct word” compared to M-ASD. Previous

research suggests that some children with SLI experience

particular difficulties with reading accuracy (Catts et al.,

2008; McArthur et al., 2000). Although C-SLI scored above

average during standardised testing, he appeared to exhibit

a relative weakness with reading accuracy in terms of

reading the book we selected for the current study. This

was reflected in the proportion of “providing the correct

word” utterances used by his mother in their interaction.

There are several limitations to consider when interpreting

the results, and considering directions for future research.

It may be that SR interactions vary across sessions. Hence,

it would be interesting to further investigate SR in these

populations across multiple interactions. Also, there is some

arrangement. Participants were instructed to read as they

would normally at home. A video camera was set up on a

tripod stand, and the researcher sat out of view as the

interaction was video-recorded for 5 minutes. Both children

were presented with an unfamiliar book supplied by the

researcher –

Volcanoes and Other Natural Disasters

(Griffey,

1998). This non-fiction book contained written passages

and colour photos depicting types of natural disasters (e.g.,

bushfires). Published by DK Readers, this book is classified

as a Level 4, aimed at children 8–10 years of age (Dorling

Kindersley, 2015). Text readability analysis confirmed that

this text would be read comfortably by children reading at

the level of typically developing 13–14 year olds (Readability

Test Tool; Simpson, 2009–2014).

Results

Word-level accuracy measures were calculated as the

number of words read correctly during the SR divided by

the total number of words that were read. C-ASD read 86%

of words correctly, and C-SLI read 76% of words correctly.

This confirms that the children were reading a book of an

appropriate level. Moreover, both children appeared to be

engaged in the SR interaction as they were initiating the

reading, and appeared to be quite responsive to their

mothers’ questions and comments. A recent study

suggested that initiation and responsiveness are key

indicators of a child’s engagement in book reading (Colmar,

2014).

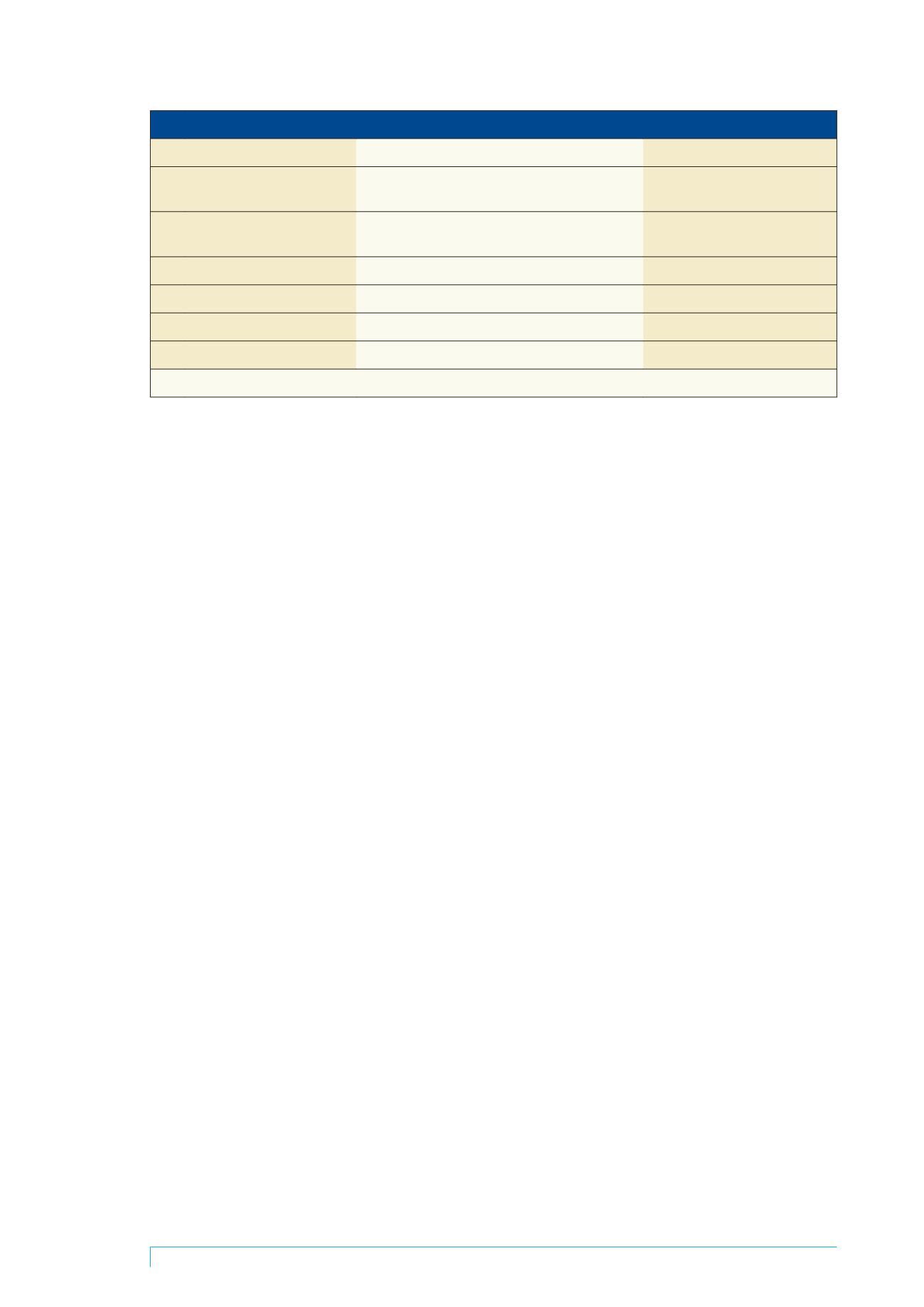

For the purposes of this study, we were solely interested

in the mothers’ utterances. Drawing on previous research

by Arciuli, Villar, et al. (2013) we explored two main types

of utterances used by the mothers in their interactions:

error correction (EC) or other (OT). An EC utterance was

defined as correcting the child’s reading error or dysfluency.

Remaining utterances were classified as OT, and were

defined as praise, comprehension monitoring, and referring

to images. Reliability measures on classifying these

utterances were conducted by an independent rater on

20% of the data and resulted in 100% agreement. Table

3 outlines the definitions and examples of the types of EC

and OT utterances.

Across the entire SR interaction which contained 49

utterances by M-ASD, 46.9% were EC, and 53.1% were

OT. Across the entire interaction which contained 88

utterances by M-SLI, 87.5% were EC, and 12.5% were

OT. In terms of some of the subtypes of EC utterances, the

data indicated that “providing the correct word” accounted

for 28.6% of all of M-ASD’s utterances, and 51.1% of all

Table 3. Definition and examples of types of EC and OT utterances

Type of utterance

Definition

Examples from data

EC Providing correct word

Mother verbalises correct pronunciation of word in an

anticipatory or correctional style

“Volunteers”

Sounding out

Mother encourages child to sound out word either

independently or in unison

“Eu-ca-lyp-tus”

Encouraging correction

Mother questions child to determine if he is correct

“Does that sound right?”

OT Praise

Mother gives child positive verbal contingencies

“Good boy”

Referring to images

Mother draws child’s attention to pictures/illustrations

“Look, what’s this? (points to picture)”

Comprehension monitoring

Mother questions child on content

“Tell me, what did you just read here?”

Note.

EC = error correction, OT = other.