34

Examples given throughout this report provide a basis for a

more general description of the structure of some of these cor-

porate networks that have a direct responsibility for the atroci-

ties conducted in the DRC and the exploitation of wildlife habi-

tats. There is no standard organisational structure, but certain

trends in their manner of organisation and in their operational

practices can be described (UNSC, 2001; UNEP, 2007). Uncrit-

ical markets ensure that there are buyers for goods at the right

price, regardless of how they are obtained, processed or trans-

ported. It is relatively easy and standard practice for companies

to build up their political networks through the judicious se-

lection of non-executive directors or by maintaining mutually

profitable relations with former board members or CEOs who

later become top government officials. These arrangements

can lapse into less innocent ones when a company and an of-

ficial, regardless of their current relationship, share a secret

from the past, such as having benefitted from military actions

in resource-rich locations. This may or may not have involved

an evil or even an illegal activity, yet investigative journalists

exist who can spin the story to make even the uncritical global

public take notice, and exposure of an ‘arms-for-oil’ trade is sel-

dom welcome in the corporate world. Shared secrets, therefore,

are important binding agents that hold companies and their

political networks together.

Illegal logging may be conducted by companies with no right

to be in the area, but also by legal concession holders, operat-

ing in several ways. Concession holders may over-harvest from

the lands granted to them, or they may exploit areas outside

these lands. It is well documented from Indonesia that conces-

sions illegally expanded their operations into protected areas

or outside of their areas, as is observed also in DRC (Curran

STRUCTURE OF CORPORATE NETWORKS

et al.

2004). The timber or processed wood products may be

smuggled secretly from the country, or even transported openly

across border stations with military or militia guards (UNSC,

2001; 2008), or sold and transported as if produced from a le-

gal concession. To avoid international tracking of the timber or

wood products, the products often change ownership multiple

times in transit. Hence, when the wood products arrive in port

in another country, it is no longer recorded as timber originat-

ing from the country in which it was produced.

The extent to which smuggling poses a problem can be seen

in official trade data on minerals and timber that are far be-

low actual exports (UNSC, 2008), possibly from 50–80% lower

than actual exports from the entire Congo Basin. A very similar

structure has been observed with illegal logging for example

in Indonesia (UNEP, 2007. Here, import figures from many

countries including China, Taiwan and Malaysia, to mention

a few, are generally far above that of officially reported exports

from Indonesia (Schroeder-Wildberg and Carius, 2005; UNEP,

2007).

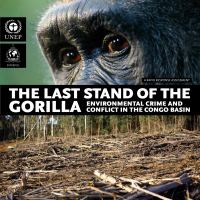

Once again, the looting and destruction of gorilla habitat is an

international concern, with multinational networks operating

openly, while the protection of the parks is a primary law en-

forcement issue. Once again, this law enforcement needs train-

ing, financing and particularly trans-boundary coordination

with the judicial system, customs and international collabora-

tion to become effective in uncovering environmental crime

involvement from end-to user.

Companies knowingly buying resources illegally exploited are,

per se, becoming complicit in criminal actions.