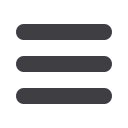

31

1999

2008

2005

2002

16

12

8

4

0

Number of Days

Number of days

of landfill blockade

due to protests

1987

1999

1999

2003

2009

2010

2015

2016

K’ara K’ara landfill established

Residents’ protests and landfill blockade

Revealed groundwater contamination

Improved infrastructure around landfill

--> Increasing urban development

Government mandates landfill closure

Landfill closure not enforced

Local authorities mandate landfill closure - closure not enforced

Landfill fire – air pollution affects 2000 families

Sources: Ghielmi G. & et al (2008) Diagnóstico sobre el nivel de

contaminación de acuíferos en el distrito 9,

Acta Nova

(4)1; Valderrama G.

(2010) El botadero de Kjara-Kjara: Un foco de contaminación que genera

conflictos sociales y compensaciones urbanísticas,

Medio Ambiente y

Urbanización

71(1); Environmental Justice Atlas,

https://ejatlas.org/1 km

High risk of contamination

of groundwater

Built up area

Elevation

Seasonal stream

River / Canal

Cochabamba

BOLIVIA

BRAZIL

K’ara K’ara

landfill

TIMELINE OF

K’ARA K’ARA LANDFILL

COCHABAMBA - BOLIVIA

2700

2700

2700

2600

2600

2600

2600

2700

2700

2800

2800

2800

2900

2800

2700

Reducing volumes of waste and promoting source separation

Swisscontact has made a significant contribution to

addressing thewaste problem inCochabamba.Their activities

have included the implementation of separate collection

schemes in Cochabamba neighbourhoods, operated by

informal recyclers and supervised by the neighbourhood

council. The project demonstrated the economic potential

of solid waste by establishing new structures for collection,

treatment and recycling. A 50 per cent reduction of mixed

waste was realized in one district and separation at source

was included in SWM plans. (Rodic, 2015a)

Collection routes were also established for informal

recyclers, with households separating recyclables and

passing them on. This programme allowed waste pickers

to generate an income of about 1,200 Bolivian Boliviano

per month (175 USD) and contributed to higher recycling

rates as well as an acknowledgement of the role of informal

waste pickers. This programme is now integrated into the

municipality’s waste management system. Between 2009

and 2012, a total of 443 jobs were created, 29,000 tons of

solid waste were collected and treated, and information on

the separation of waste at source was provided to 475,000

households (Rodic, 2015a).

Bolivia is making a concerted effort to move away from

dumping and landfilling, towards initiatives that focus on

small-scale open air composting of organic waste. Municipal

waste trucks have started to collect organics, recyclables and

residual waste separately, and private recycling companies

are emerging which use materials from industry and storage

centres (they receive materials from waste pickers). The

future of the Bolivian waste market appears to be positive

– with new investments and initiatives, and good intentions

are all around (BreAd B.V. and MetaSus, 2015). In 2012, Bolivia

invested USD 20 million in waste management (Environment

News Service, 2012) and the growth in demand for waste is

estimated to be 1 per cent per year (BreAd B.V. and MetaSus,

2015). Although these numbers are promising, efforts

are still small-scale and scattered, and new initiatives are

needed. Opportunities exist for private companies (which

already play an important role in waste collection and

operation services) to engage in waste management (for

example, biogas production) and cooperation is needed to

make waste composting and sanitary landfills more viable.

These developments will create a more effective waste

management system, which may increase the willingness of

the population to pay for waste services.