10

JCPSLP

Volume 17, Number 1 2015

Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology

Availability of the ICS

The translated versions of the ICS are freely available from

http://www.csu.edu.au/research/multilingual-speech/ics.Each version of the ICS is available in two formats: a

monolingual format and a bilingual format with the English

translation added in a smaller font. On the website and the

pdf versions of the ICS the translators have been

acknowledged by name and affiliation. In the footnote of

each pdf version of the ICS, a suggested reference is

provided that acknowledges the authors and translators. A

creative commons licence has been added (

http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/) that allows

users to copy and use the ICS, as long as appropriate

attribution is made, the material is not used for commercial

purposes, and revisions of the material are not distributed.

Users are welcome to contact the authors about additional

uses of the ICS.

Conclusion

While over 20% of Australian speech pathologists provide

services in languages other than English (Verdon, McLeod,

& McDonald, 2014), most Australian speech pathologists

encounter children who do not speak the same languages

as they speak. The ICS is a promising tool to provide

first-phase screening of children’s intelligibility so as to

determine whether additional assessment is required with

the assistance of an interpreter or colleague who speaks the

language(s) of the child. International collaboration between

speech pathologists, linguists, and translators has resulted

in the availability of the ICS in 60 languages and

international research is underway to validate, norm, and

examine the clinical applicability of the ICS across the world.

References

Caesar, L. G., & Kohler, P. D. (2007). The state of school-

based bilingual assessment: Actual practice versus

They found that the ICS showed good internal consistency

and test-retest reliability. Criterion validity was established

by comparing results between the two groups of children.

For the typically developing group the mean score was 4.6

(

SD

= 0.5) and this was significantly different from mean

score achieved by the children with speech sound

disorders (

M

= 4.1;

SD

= 0.7). The effect size was large

d

=

0.74. Sensitivity of 0.70 and specificity of 0.59 was

established as the optimal cut-off. Tomi´c and Mildner (2014)

used the ICS with 486 Croatian-speaking children aged

1;2–7;3 and compared parent- and teacher-reported

intelligibility. They found that across the children, the mean

score was 4.4 (

SD

= 0.5, range = 2.4–5.0). Kim et al. (2014)

used the ICS with 26 Korean-English speaking children in

New Zealand who were aged 3;0–5;5 and reported the

mean score was 4.4 (

SD

= 0.5). Kogovšek and Ozbiˇc

(2013) used the ICS with 104 Slovenian-speaking children

aged 2 to 6 years and found that across the children the

mean score was 4.6 (

SD

= 0.5, range = 2.7–5.0). They

found that parents and immediate family members were

more likely to understand the children, and that strangers

were least likely to understand the children.

To date, there has been remarkable consistency across

these international studies and those that have been

undertaken with English-speaking children (McLeod et

al., 2012b; McLeod et al., 2014). It may be the case that

across the world preschool children who achieve a mean

score above 4.2 may be considered to be developing

typically; whereas those who score below 4 may require

additional assessment. Additional studies are underway in

a range of countries including: Brazil, Cambodia, Denmark,

Fiji, Iceland, Iran, Israel, Jamaica, Germany, New Zealand,

Slovenia, South Africa, Sweden and Vietnam. Further

studies will confirm whether this hypothesis is applicable

across languages.

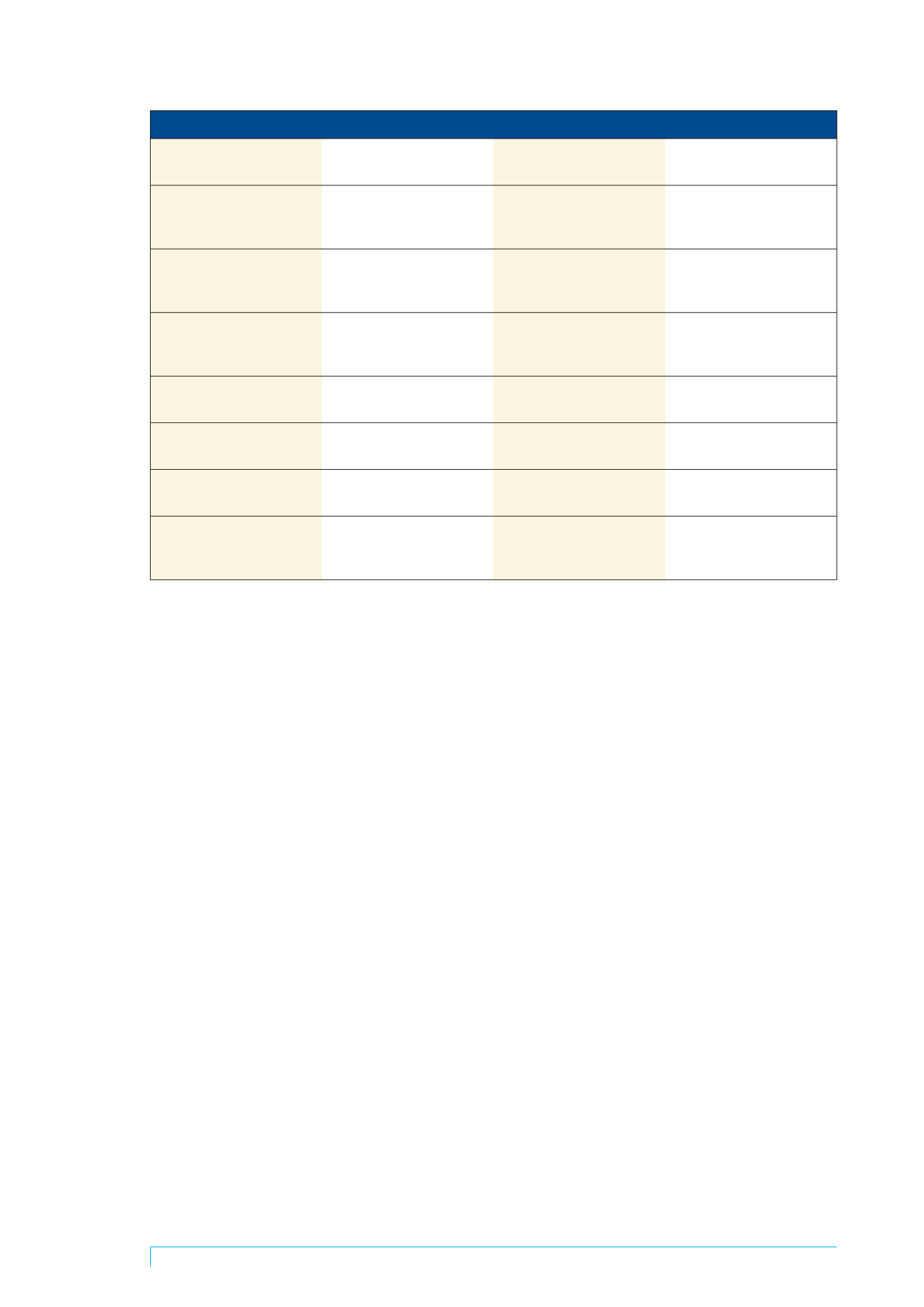

Table 1. Translations of the Intelligibility in Context Scale (continued)

Serbian

Разговетност у контексту

скале: Српски

Thai

(

ภาษาไทย

)

แบบประเมิ

นการฟั

งเข้

าใจคำ

�

พู

ด

Sesotho (Sesotho)

Teko ya kutlwisiso ya puo:

Sesotho

Tongan

(Lea Faka-Tonga)

Ko e Tu’unga ‘o e Poto’i

Faka’atamai ‘i hono

Fakasikeili: Lea Faka-Tonga

Slovak

(Slovak)

Škála hodnotiaca

zrozumitel’nost’ re ˆci v

kontexte: Slovak

Tshivenda

(Tshivenda)

Tshikalo tsha u Pfesesea ha

Kuambele: Tshivenda

Slovenian

(slovenš ˆcina)

Lestvica razumljivosti govora

v vsakdanjem življenju:

slovenš ˆcina

Turkish

(Türkçe)

Ba ˘glam Içi Anla ¸sılabilirlik

Ölçe ˘gi: Türkçe

Somali

(Soomaali)

Cabbirka Garashada

Hadalka: Soomaali

Vietnamese

(

Việt

)

Sự Dễ hiểu trong phạm vi

ngữ cảnh: Việt

Spanish

(Español)

Escala de Inteligibilidad en

Contexto: Español

Welsh

(Cymraeg)

Graddfa Eglurder mewn

Cyd-destun: Cymraeg

Swedish

(Svenska)

Skattning av förståelighet i

kontext: Svenska

Xhosa

(isiXhosa)

Ulwazi olu Phezulu: isiXhosa

Tagalog

(Tagalog/Filipino)

Antas ng Pag-unawa ng

Iba’t Ibang Tao sa

Pagsasalita: Tagalog

Zulu

(isiZulu)

Isikalelo sesigqi

Sobuhlakani: isiZulu

Note: Translations in isiNdebele, Sepedi, Setswana, SiSwati, and Xitsonga are forthcoming.