www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au

www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au

JCPSLP

Volume 17, Number 1 2015

21

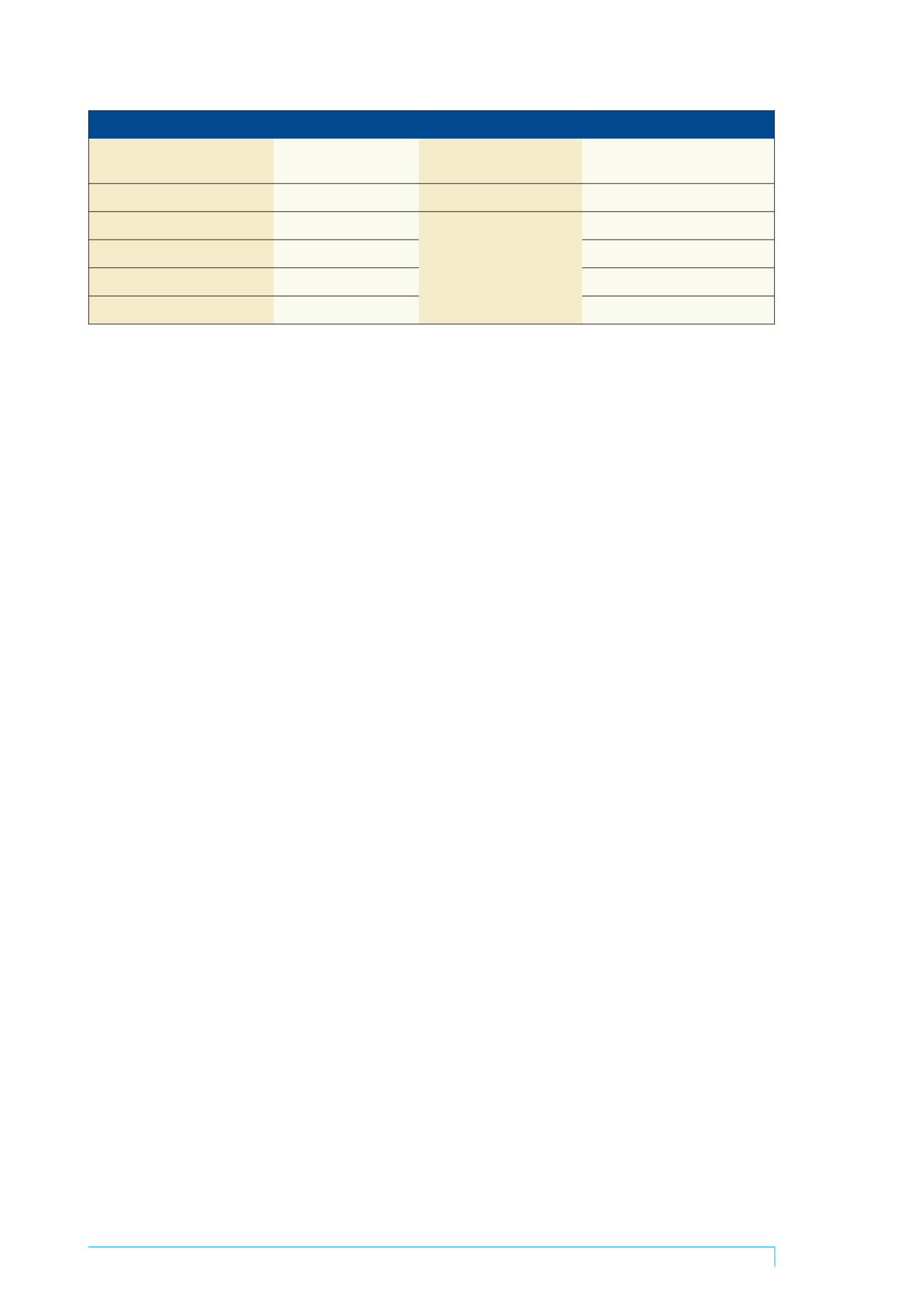

May 2013). This indicates that approximately 10% of the

potential target population was recruited for this study. The

average number of years spent working as a SLP was 6.70

(

SD

= 4.8) with 16.4% respondents indicating they have

worked for more than 15 years. Table 1 details the regions

in which the respondents provided services and how this

compares to the general Australian SLP population and to

the results from a recent survey into general aphasia

rehabilitation practices by Rose et al. (2014). Respondents

were sourced from mailing lists of the Centre for Clinical

Research Excellence in Aphasia Rehabilitation and the

Speech Pathology Australia Email Google Chat Group.

Recruitment advertisements were also placed in the

Speech Pathology Australia national and state branch

e-newsletters. Ethics approval for this study was granted by

the La Trobe University Faculty of Health Sciences Human

Ethics Committee (FHEC 12/193).

Questionnaire

A 30-item internet survey was piloted on a group of six

volunteer SLPs experienced in aphasia rehabilitation. The

final survey consisted of 31 items and was expected to take

30 minutes to complete. The survey was available to

respondents during March and April 2013. Results from

one section of the survey dedicated to interpreting services

will be reported in a future publication. The questionnaire is

provided in the Appendix.

Analysis

A content analysis was conducted on text responses to

open questions (Berg, 1998). Responses for each question

were given a thematic code by the first author. Similar

codes were grouped together to generate a “theme”. All

themes that were generated were then analysed to

determine if macro-level themes which encompassed

themes with related content were present. Using the

themes that were generated, the second author re-coded

10% of all the responses. Point-to-point inter-rater

agreement was achieved at 91.4%. Descriptive statistics

were used to analyse responses to closed questions.

Descriptive analyses are used to describe different

characteristics of a population, and commonly used in

survey research (Portney & Watkins, 2009). Frequency

counts of nominal and ordinal data were conducted and

expressed as numerical figures and percentages. Measures

of central tendency (mean) and dispersion (range and

standard deviation) were calculated for ratio data.

Results

This paper reports the survey findings with regards to the

knowledge, skills, and education of our profession, and

areas of clinical practice relevant to these topics. While the

However, a similar investigation of specific knowledge and

skill gaps in Australia has yet to be made.

The current body of research raises concerns about the

state of the knowledge, skills, and, consequently, the quality

of the services of SLPs working in aphasia management

with CALD communities in Australia. Yet, little is known

about what specific knowledge and skills gaps need to

be addressed. Importantly, there is also little information

regarding aphasia intervention practices. Large-scale

investigation into SLPs’ satisfaction and confidence levels

regarding the overall range of services provided to CALD

clients is absent. Such information along with the perceived

knowledge and skill needs of clinicians can inform

professional development (PD) and university programs of

potential improvements and move us closer to providing

quality culturally competent aphasia management services.

Aims

This research aimed to investigate current demographic

characteristics, perceived levels of knowledge, skills and

education, aphasia rehabilitation practices, and perceived

levels of confidence and satisfaction of SLPs working in

aphasia rehabilitation in Australia with CALD clients. For the

purpose of this paper, we use the term CALD as a broad

descriptor to refer to individuals other than the English-

speaking Anglo-Saxon majority. We acknowledge that in

common use the term CALD is often used to refer to individuals

born overseas (Sawrikar & Katz, 2009); however, we chose

not to focus on migrant status as a defining feature of the

term in our survey. We also note that the term CALD does

not generally include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

communities and we have not focused on the issues

specific to these people; however, we have included

occasional mention of these communities in our paper

where our participants have raised relevant issues. We also

investigated the challenges faced, and changes required,

as reported by SLPs when working with CALD populations.

Method

Participants

Members of the target population were SLPs with a

caseload including patients with aphasia (PWA) in Australia

at the time of the survey. The survey link was accessed 88

times; however, only 73 surveys were completed and

analysed. Fifteen incomplete surveys were excluded

because the respondents completed less than 40% of the

questions. At the time of data collection, there were

approximately 720 SLPs on a national database held by the

Speech Pathology Association of Australia who self-listed

adult language disorders (including aphasia) as a specialty

area in their profiles (M. Bradley, personal communication, 7

Table 1. Localities of service provision for Australian SLPs

Locations

Current research

Rose et al. (2013)

Speech Pathology Association of

Australia (2003)

Capital cities/ metropolitan area

78.1%

58.5%

84%

Regional cities

16.4 %

41.5% (combined regional and

rural locations)

10.7%

Regional towns

6.8%

3.1%

Remote area

1.4%

0.8%

Very remote area

0

0