28

JCPSLP

Volume 17, Number 1 2015

Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology

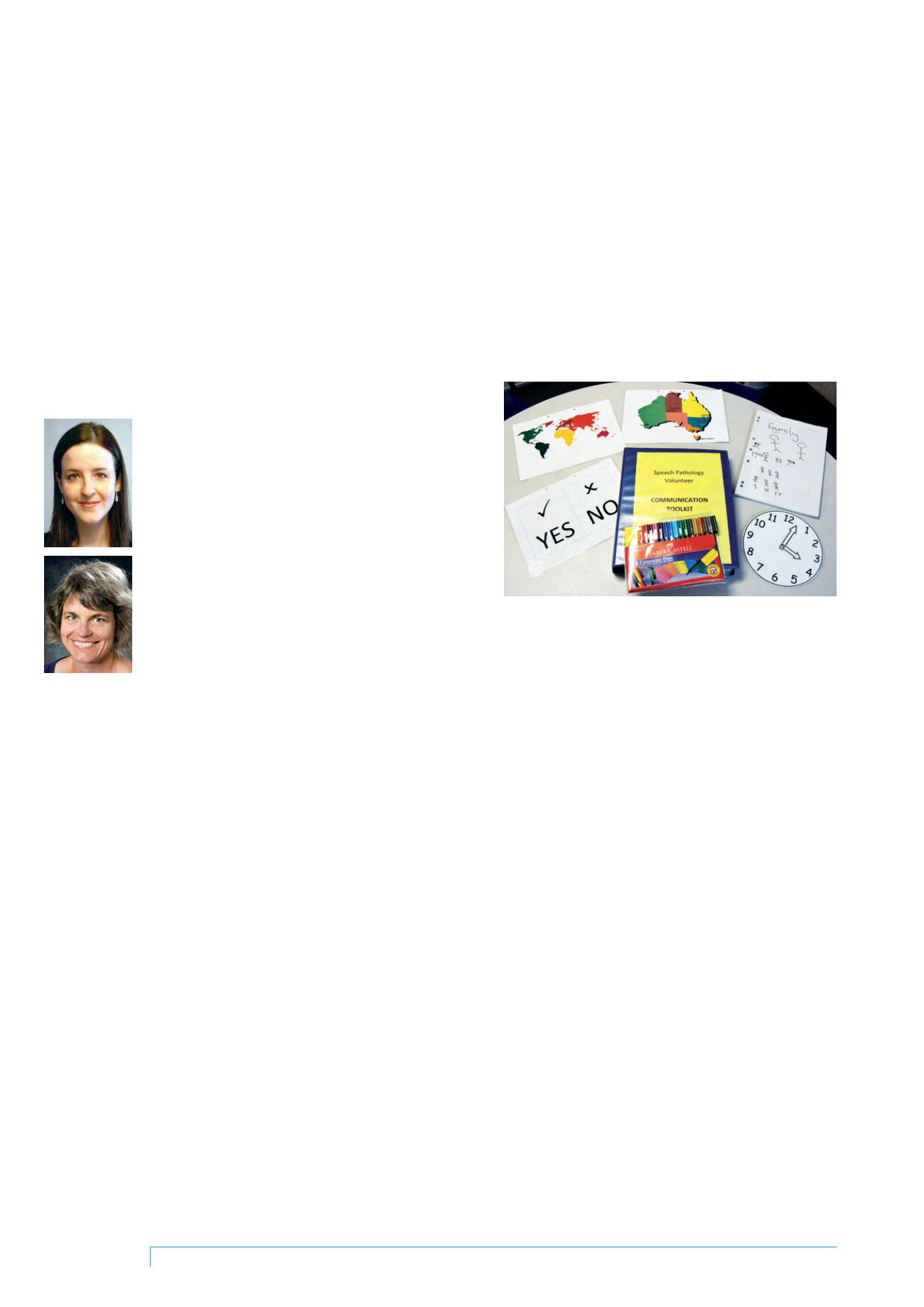

a range of different maps, alphabet, and number boards,

picture-based resources, topic cards, and word lists such

as the months of the year and days of the week. Finally, a

communication partner training program, tailored to meet

the needs of this new program and the hospital setting was

developed. This program is described in detail below.

Supported conversation volunteer

training

Information and resources from The Communication

Access Toolkit (Parr, Wimborne, Hewitt, & Pound, 2008)

and the Supported Conversation for Adults Training

Workshops (The Aphasia Institute,

http://www.aphasia.ca/health care-professionals/ai-training/) were combined with

newly developed resources to create three separate

workshops. In the first workshop, volunteers were

org/)and the Aphasia Institute

(www.aphasia.ca/) and

had completed training in supported conversation and the

second author who had noticed that many inpatients with

communication disorders in the hospital appeared bored

and had few opportunities to engage in conversation.

Together, they saw the opportunity to provide some Angel

Volunteers with supported conversation partner training

so that patients with acquired communication disorders

following stroke could have more opportunities for

enjoyable social interactions. While the authors were aware

of a home-based supported conversation partner scheme

for people with chronic aphasia living in the community

(McVicker, Parr, Pound, & Duchan, 2009), this was the first

program that they were aware of that provided supported

conversation opportunities to hospital inpatients with

acquired communication disorders.

Members of the speech pathology department

conducted a short survey of ten patients with acquired

communication disorders to gauge their interest in the

proposed program. All ten patients stated that they enjoyed

having good conversations in hospital but only three said

they were actually having good conversations. Six of the ten

patients indicated that they would like more opportunities

for good conversations. They also stated that health was

the main topic of conversation in hospital and they had a

desire to discuss other topics. This short survey indicated

that there would be interest from patients for more

opportunities for social conversation, therefore a Supported

Conversation Volunteer (SCV) program was piloted.

The Supported Conversation

Volunteer Pilot Program

A number of steps were taken to establish the pilot SCV

program. The speech pathology manager (first author)

engaged with the key stakeholders including the volunteer

manager and acute stroke and inpatient rehabilitation nurse

unit managers to inform them about the proposal and to

gain their support. Then, the first author submitted the

proposal to the Allied Health Quality Committee and it was

subsequently approved. The volunteer manager then

approached two volunteers to participate in the pilot. These

volunteers had already completed all of the necessary

induction and training processes required to volunteer at St

Vincent’s. These included an interview, reference checks, a

police check, attendance at a half-day orientation program

for all new staff, and a full-day volunteer orientation program.

The speech pathology team provided information and

education about the SCV program to nursing, allied health,

and medical staff in the acute stroke and inpatient rehabilitation

units within the hospital. They also developed guidelines,

procedures, and resources to support the implementation

and evaluation of the program. These included criteria to

identify suitable patients for the program, procedures for

referring patients, and a referral form. Criteria included a

recent diagnosis of stroke, presence of a post- stroke

communication disability, ability to concentrate for 20–30

minutes, conversational English, and an interest in being

visited by a volunteer. A position description that outlined

the roles and responsibilities of supported conversation

volunteers and a document detailing the procedures for

volunteers were also written. To support the volunteers in

conversation with patients, a communication history

questionnaire and resource folders were also developed.

The communication history questionnaire was designed to

be completed by the patient or a close other and included

information about the patient’s premorbid communication

style, family, friends, lifestyle, hobbies, and interests. The

resource folders included paper and markers, whiteboards,

Julia Shulsinger

(top), and Robyn

O’Halloran

orientated to the program, given theoretical information

about acquired communication disorders and supported

conversation, and then participated in role plays. Further

details about the first workshop are provided in Table 1. The

second workshop, described in Table 2, included

observation of a speech pathologist using supported

conversation with inpatients with acquired communication

disorders. These patients were current inpatients who had

been referred to speech pathology and had agreed to

assist with the training. The volunteers were then given the

opportunity to try supported conversation strategies with

these patients under the supervision of a speech

pathologist. The final workshop, described in Table 3,

provided volunteers with further opportunities to use

supported conversation strategies with participating

patients with acquired communication disorders.

Opportunities for feedback and reflection were also

included as part of the second and third workshops. The

volunteers completed all of the training and completed a

post-training questionnaire, which indicated that they felt

confident providing conversation support to inpatients with

acquired communication disorders before the SCV program

commenced.

The pilot program

The pilot program began in February 2011 and ran for 6

weeks. Patients were referred by their treating speech

pathologist and the coordinators allocated the patients to

each volunteer. The treating speech pathologists on the

rehabilitation units also scheduled the volunteers’

appointments on the patients’ weekly rehabilitation

timetables. Every week, each volunteer engaged 1–2

patients in approximately 30 minutes of conversation each.

In total, over the six-week trial, the two volunteers engaged

ten patients in a total of 24 hours of conversation.

After each supported conversation, the volunteer

completed a reflective journal and documented the

amount of time spent with the patient, the topics that were