ARCHAEOLOGY

Eternal India

encyclopedia

800°C. In the course of excavation at Daimabad a few furnaces

used for melting copperbronze and dumps of slag and ash were

found. It is observed that the Debari copper mines near Udaipur

were worked more than 2000 years ago by the Aharians, who could

extract metal from ore and melt it, but were not good at casting. On

the other hand, the copper-workers of Kalyadi in Hassan District of

Karnataka could extract almost the entire metal from the ore which

is borne out by the analysis of the slag from the furnaces at the foot

of the hill. The slag contained less than 0.2% copper whereas in the

modern copper smelters 2% metal is left in the slag. The Kalyadi

technique appears superior to that of modern technique of extrac-

tion of copper (IAR 1978-79).

The Harappans obtained gold and silver from distant places eg.

gold from Afghanistan and Kolar Gold Mines in Karnataka, copper

from Khetri and perhaps Iran and Oman. The main purpose of hav-

ing settlements in Afghanistan and Tajikistan (Altin Depe) was to

have control of the source of raw material. Such considerations took

them to Bhagatrav in South Gujarat wherefrom they co.uld get

agate, carnelian, jasper and chert.

Botany and Agriculture

As early as the fifth millennium B.C. rice was grown in Ma-

hagara in Uttar Pradesh and cotton in Mehrgarh in Baluchistan.

Wheat, barley, sesame and date were used by the pre-Harappans

as well as Harappans in the third millennium B.C. Multiple cropping

was practised in Kalibangan and the plough was in use; a terracotta

model of the plough is found in Banawali. The seed-drill with

several tubes for sowing must have been known to the Harappans

as it is incised on a terracotta seal from Lothal. Gypsum was

stored in Kalibangan for reclaiming salt-charged land. It served as.

a chemical fertilizer. The granaries of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro

are a further improvement over the granary of Mehrgarh.

Communication of Thought

The Indus Script hitherto considered undeci-

pherable has been deciphered to a very large extent

on the basis of a key provided by the Late Harappan

Script in which out of 24 cursive basic signs 17 are

identical with the Semitic alphabetic signs. In fact

the Semitic alphabet has been derived from the sim-

plified Late Harappan Script which gave rise to

Brahmi Script in the 14th -15th century B.C. The

transition phase from Indus to Brahmi alphabetic

writing can be seen in the Bet Dwaraka inscription.

But for the simplification of a partly pictographic and

partly logographic writing into an alphabetic script

the sophistication in civilization which depends on a

quick and easily understood script would not have

been possible. The greatest contribution of the Har-

appans to human progress is the alphabetic writing.

The author’s decipherment is now accepted by ex-

perts (D. Diringer 1975, 1985 De ■ Sousa; David

Frawley

1991;

Konrad

Elst

1993;

Grum-

mond 1992; Srikanth Talageri 1993) in Berkeley and

other universities. The criticism by Zvelebeil has

been squarely met by S.H.Ritti, the expert Epigra-

phist (Ritti 1985, 1-24).

Engineering

Although small towns were built in the 5th-4th millennium B.C.

they were not planned in the real sense of the term until the

Harappans took to serious town-planning with a blueprint showing

various sectors of the town and their functions. The Harappan

planning was conditioned by two factors namely the challenges

from the sea and the river and provision of maximum civic amenities

to all classes of people. Harappan cities were great industrial and

commercial centres and their prosperity depended on trade. The

raw materials for industries had to be procured from distant places

and the products had to be distributed to all corners of the Empire

and also exported to far off ports. The dichotomy of planning lay in

dividing the town into the Citadel or Acropolis and the Lower Town.

The entire town built on artificial terraces of mud bricks was divided

into a number of blocks all fifter-connected by broad and straight

roads cutting at right angles. Neatly-built underground and sur-

face drains were provided to keep the city clean. Every house had

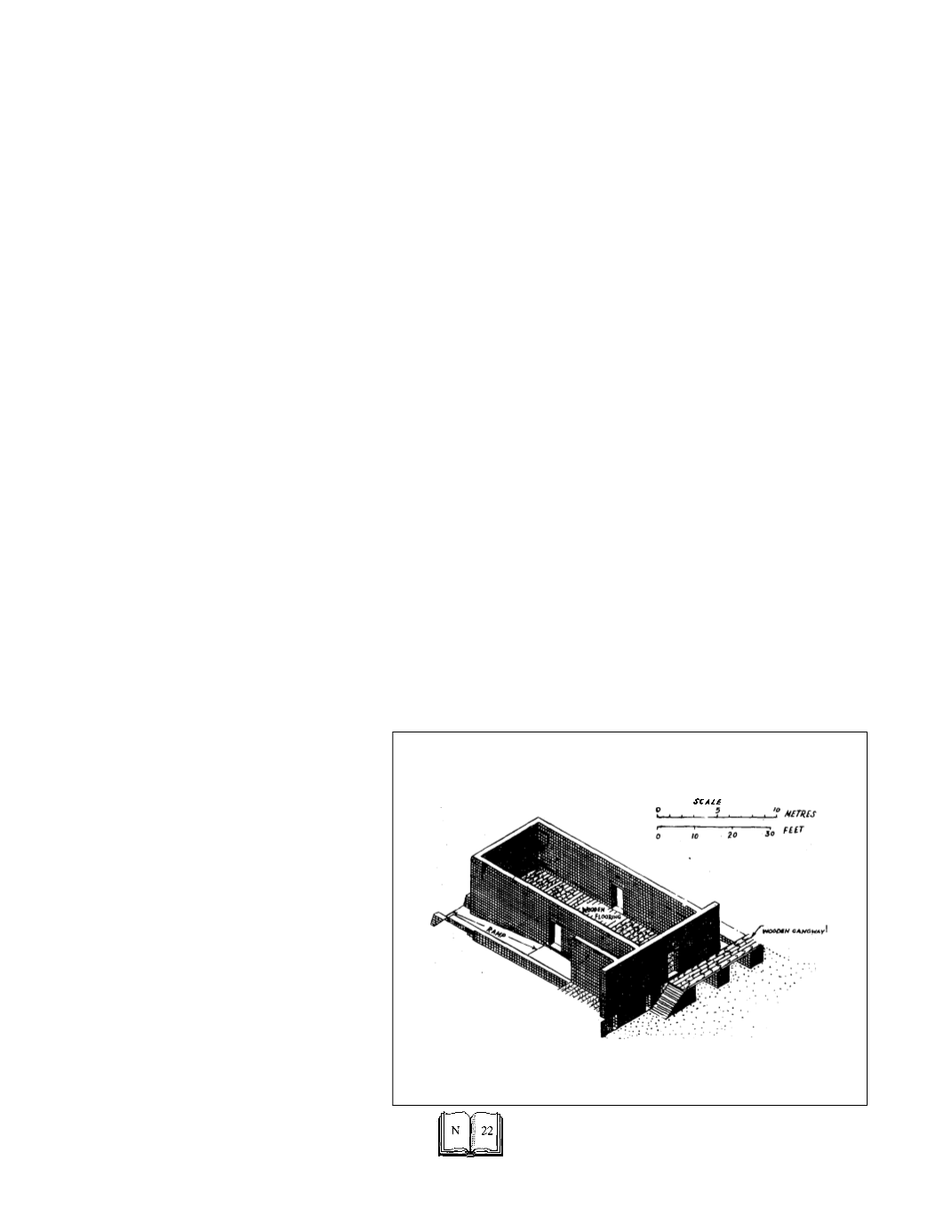

paved bathrooms. Granaries (fig:36) were built in Harappa and

Mohenjo-Daro with necessary airvents for proper presentation of

grains. A unique contribution of the Harappan engineers to mari-

time trade is the construction of a tidal dock at Lothal (fig:9). It

could accommodate 30 to 40 ships at a time. Automatic desiltation

was ensured by providing a spillway which had a lock-gate, device.

This is the first ever example of putting to practical use one’s

knowledge of tides, waves and currents. A warehouse of 64 blocks

with airvents and wooden canopy was built near the dock. The

800m long wharf facilitated handling cargo.

Late Harappa Culture

The term Late Harappa Culture was first introduced in 1963 to

distinguish the Mature Harappa Culture from its decadent or deur-

banized phase in Rangpur, the former designated as Period IIA and

the latter as Period IIB. The next phase of Transformation of the

Late Harappa into the Lustrous Red Ware Culture was called Pe-

riod IIC. But after a large scale excavation of the mature and de-

clining phases of Harappa Culture the term Late Harappa has been

HARAPPA GRANARY:

CONJECTURAL RESTORATIONOF A ROOM

Fig : 36 -- Harappan Granaries