Eternal India

encyclopedia

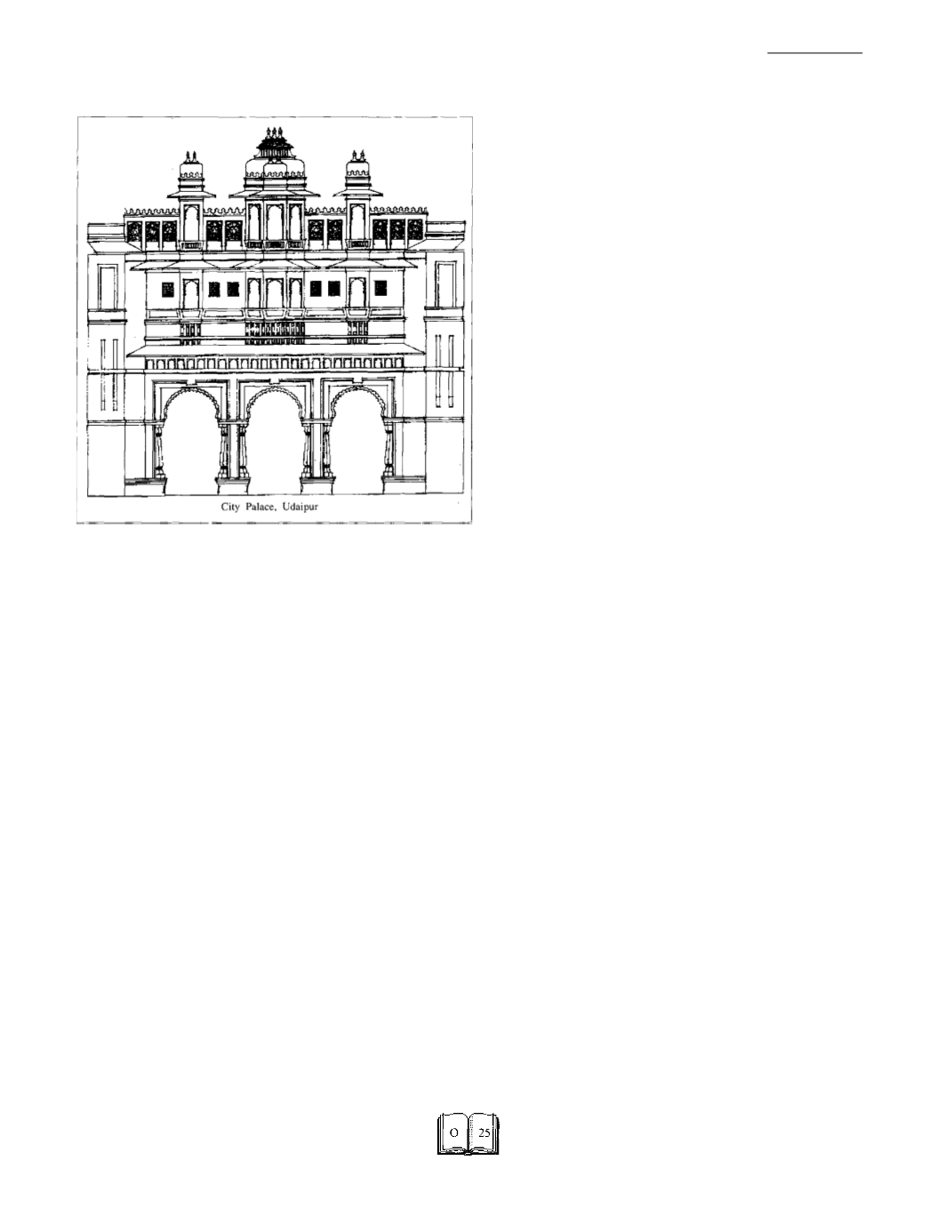

ARCHITECTURE

PALACES

Palace architecture has developed in India in parallel with the

development of fort architecture. The royal palace was always

located in a well fortified city. The palace complex was thus an

important feature of the notable forts and fortified cities of ancient

and medieval India.

Many of the palaces of the great kings of India have completely

vanished. Some of the imperial capitals, such as Thaneswar, Ka-

nauj, Vijayanagar and Delhi, were plundered and subjected to re-

lentless demolitions. It is only possible to visualise the glory of

ancient palaces in India on the basis of historical writings, Sanskrit

literature and

Shilpa Shastras

(the canonical books of Hindu crafts-

men).

Ashoka's palace at Pataliputra is described by Megasthenes as

no less magnificent than the palaces of Susa and Ekbatana. It was

still standing at the beginning of the 5th c A.D. when Fahien visited

India, but by the time Hiuen Tsang visited the city the palace had

been burnt to the ground and the place was almost deserted. Recent

excavations have revealed the remains of a great hall, with stone

pillars.

This graphic description of the palace of King Harshavardhana

is given by Banabhatta in his

'Harshacharita':

The palace complex was situated on a Giridurga or hill-fort

which has strong stone ramparts with slits for shooting arrows.

The entrance to the fort was through a big gateway flanked by a

storeyed tower.

Outside the gateway and adjacent to it were erected some tall

pedestals for mounting on the back of the elephants (

uchhak-

umbhakuta).

These are also termed as

'Hastinakha'

in earlier

literature.

The large door-leaves of the gateway when closed were barred

at the rear with a strong wooden bolt, fixed transversely and

inserted into the wall of the fort; this was to*be pulled out by hand

(hastargala-danda)

to open the gateway.

The palace was built at a central place. There one came across

the

Brahmastambha

or the foundation pillar of the royal palace.

This appears to be the main pillar of the building from which the

main plumbline

(Brahmasutra)

was determined for the whole con-

struction. It appears to have been a ceremonious pillar inset with

ivory scrollwork.

The palace complex was entered through a principal entrance

known as Rajadvar or the royal gate. On top of the entrance there

were imposing carved figures of combating lions and elephants and

hence it was known as

'Simhadvar'

or

'Simhapratoli'.

The palace was well guarded. There was no restriction against

entry in the Skandhvar which was open to the public, but the entry

into the palace complex was controlled strongly. The palace was

guarded by the Bahya-pratiharas, i.e, chamberlains posted outside

the palace. Above the entrance to the royal palace there was a

minstrels' gallery where music was played at a stated time accom-

panied by the sound of the drum

(Dhundubhi-Dhvani)

Inside the Rajkila there was a regular scheme of spacious and

extensive courts

(amantam bhunanabhyantore, Kakashya).

The

palace of Harsha was planned in three courts

(Samantikra

Myatrinika, Akshyantarini).

In the first court, at the left side of the

main gate was an extensive pavilion

(Akasthanamandapa)

for the

royal elephants

(ibhadhisyagara).

Here the king's own elephant

Darpasata, was kept. On the right side opposite the elephant

stables was the stable

(manduri)

for the king's horses who were

known as Bhupals, Vallabha, Turanga. Bana often refers to the

king riding on the royal elephant or horse while entering the gate

crossing the forecourt

(Mahasopana)

leading to the hall of public

audience.

In the centre of the second court was located

'Bahyasthan-

amandapa'

i.e. the Hall of Public Audience, also called 'sabha'. In

front of it was the extensive court, called

Ajira’.

The king had the

privilege of riding his horse or elephant upto this point. In order to

gain access into the .audience hall the king had to dismount at the

foot of the staircase. The audience hall was approached by these

steps.

The king occupied the royal seat in the audience hall. This seat

or throne was known as

Indrasana

or

Simhasana.

It was a raised

seat as high as an elephant and had the shape of an

AmbarV

or hand

placed on the back of an elephant. The throne was adorned with

rows of bells and small fly whisks. On this raised ivory throne was

placed a small ivory coach.

Bana also indicates the presence of the Goddess Lakshmi

behind the king's throne. The figure was produced by inlay work

(Bhakti)

probably of gold in ivory. It is also possible that the figure

of Vishnu (Lord of Lakshmi) was done in inlay at the back of the

throne and Lakshmi attended on him in an invisible form.

The

'Visvakarma Vastushastra'

in its 12th chapter states that

the royal palaces may be constructed either in the centre of the city

or at the place assigned for it in particular type of cities. The form

of the site is best chosen as a square but rectangular sites are also

allowed. The dimension may be anything from 50 to 500 dandas or

it may be 1/8 or 1/16 of the entire area of the city. The several

buildings shall usually have storeys, and special halls on the first

and second floors called

'Chandrasalas'

shall also be constructed.

The palace may have a single gate.