8

JCPSLP

Volume 15, Number 1 2013

Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology

& Kresheck, 1983) and a spontaneous language sample

scored for grammatical complexity (see Procedures).

Language assessment results revealed that all

participants experienced grammatical deficits affecting

the accurate production of 3rd person singular present

progressive sentences containing a subject-verb-object

(e.g., The boy + is eating + a hot-dog

or

He + is eating

+ a hot-dog). Following consent to participate, 22 of

the 34 preschoolers were randomly selected to receive

intervention, leaving 12 participants to remain on the waitlist

for intervention. This selection allowed for equal numbers

in each intervention group and in the control group (see

Table 1). Half of the participants in intervention received

computer-assisted intervention (n = 11) and the other

half received table-top intervention (n = 11). Results of

Univariate ANOVAs revealed non significant between-group

differences for age (

p

= .126), gender (

p

= .902), nonverbal

IQ (

p

= .443), receptive language word-level (

p

= .087),

and receptive language sentence-level (

p

= .374), and

expressive grammar on the SPELT-P (

p

= .080) and DSS

(

p

= .127). There was no study attrition. Table 1 describes

participants’ demographic information.

Procedures

Assessment

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) or graduate SLP

students evaluated participants’ language and cognitive

skills during a 90-minute individual assessment in a clinical

setting to determine participant suitability (pre-intervention).

This session included the collection of a 45-minute

spontaneous language sample during play (using a

standard procedure and including a dollhouse, toy

household objects and people and the

Spot Bakes a Cake

[Hill, 2003] and

Where’s Spot

[Hill, 2000] books). At least

100 intelligible utterances were collected and digitally

recorded from the participants at post-intervention and 3

months post-intervention, representing a break in

intervention (cf. Washington et al., 2011), to establish

spontaneous language outcomes associated with

intervention. Language samples were transcribed and

coded by assessors who were blind to group assignment

and assessment time points.

DSS procedures were used to analyse the language

samples (Lee, 1974). To obtain a DSS score, 50

consecutive utterances containing a subject and verb

were selected. Each utterance was scored for grammatical

accuracy (i.e., the DSS sentence point) and the eight DSS

The current study

The hypothesised link observed between grammatical

errors and processing constraints suggests that SLI has a

complex nature that necessitates grammatical language

interventions (Leonard et al., 2007). A secondary analysis of

the Washington et al. (2011) data was completed for the

DSS scored language samples to determine if expressive

grammar intervention facilitated accelerated growth (i.e., to

within normal limits), representing performance outside the

pre-test range for the spontaneous use of grammar skills

better than no intervention. Additionally, the authors tracked

decreases in per cent error rates for targeted grammatical

categories (e.g.,

personal pronoun

,

main verb

,

sentence

point

) for intervention and no intervention groups. The

following research questions were addressed:

1. Do computer-assisted and table-top intervention result

in accelerated growth in grammatical development

compared to no intervention?

2. Do computer-assisted and table-top intervention result

in significantly lower per cent error rates for targeted

grammatical categories compared to no intervention?

Method

Participants

Following ethical approval, 34, 3- to 4-year-olds (

M

= 4;4

months,

SD

= 5 months) who were randomly selected from

an intervention waitlist at a government-funded preschool

speech-and-language initiative in Ontario, Canada met the

Washington et al. (2011) study criteria (see below). Their

parents identified them as Caucasian (n = 32), Asian (n = 1),

or other (n = 1) and monolingual English speakers. The

sample included 27 boys and 7 girls, residing in urban and

rural regions.

All participants met the diagnostic criteria for SLI of

an expressive nature as outlined in the Washington et

al. (2011) study. These included normal hearing range,

normal receptive language and nonverbal cognition, i.e.,

one standard deviation from the mean on the Peabody

Picture Vocabulary Test-IIIB (PPVT-IIIB; Dunn & Dunn,

1997); the receptive portion of the Clinical Evaluation of

Language Fundamentals-Preschool (CELF-P; Wiig, Secord,

& Semel, 1992); and the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test –

2: Matrices Subtest (KBIT-2; Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004).

For expressive grammar, children demonstrated skills at or

below the 10th percentile, on the Structured Photographic

Expressive Language Test-Preschool (SPELT-P; Werner

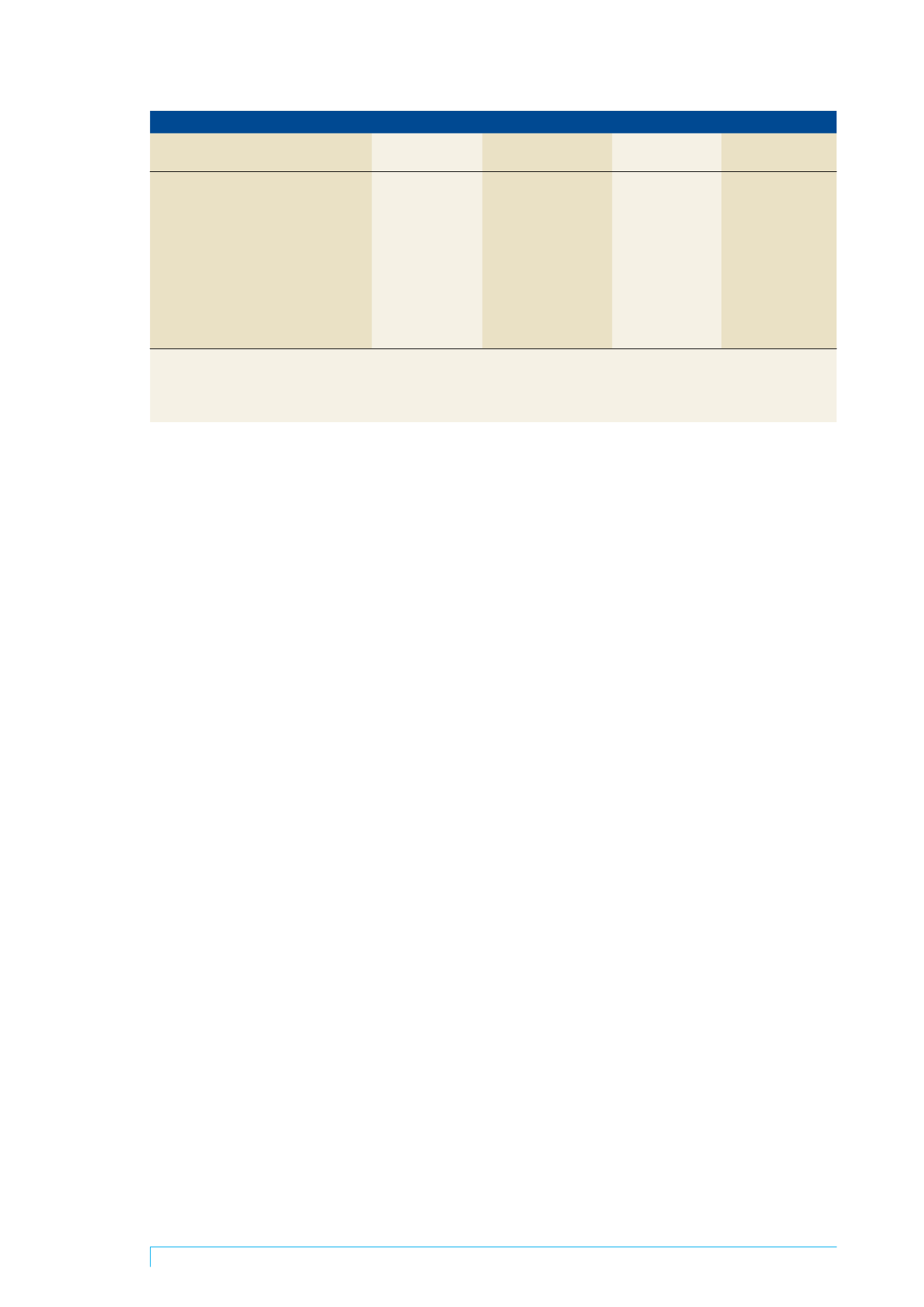

Table 1. Preschoolers’ pre-test characteristics

Total sample

Computer-assisted

Table-top

No intervention

(n = 34)

(n = 11)

(n = 11)

(n = 12)

Age-range

3;6 to 4;11

3;11 to 4;6

4;2 to 4;10

3;6 to 4;11

Gender-distribution

Female = 7

Female = 3

Female = 3

Female = 1

Male = 27

Male = 8

Male = 8

Male = 11

Receptive-word (PPVT-IIIB)

101.85 (4.88)

103.64 (5.71)

102.73 (3.77)

99.42 (4.30)

Receptive-sentence (CELF-P)

101.21 (6.95)

103.36 (8.65)

100.36 (8.10)

99.75 (2.90)

Expressive -SPELT-P

*10.26 (3.97)

*10.09 (2.30)

*12.27 (3.38)

*8.58 (4.99)

Expressive-DSS

*4.84 (.82)

*4.81 (1.08)

*5.21 (.66)

*4.51 (.54)

Expressive-MLU

*5.26 (.76)

*5.17 (.73)

*5.62 (.75)

*5.01 (.70)

Nonverbal IQ (KBIT-2 matrices subtest)

109.15 (10.10)

112.27 (12.35)

108.45 (9.61)

106.92 (8.24)

*Raw score.

Note.

Means reported with standard deviations in parentheses. Standard scores are reported for all measures, except for expressive-language.

Receptive-word (PPVT-IIIB; Dunn & Dunn, 1997), receptive-sentence (CELF-P; Wiig, Secord, & Semel, 1992), expressive-SPELT-P (Werner &

Krescheck, 1983), expressive-DSS (Lee, 1974), expressive-MLU (Brown, 1973; Miller, 1981), nonverbal IQ (KBIT-2; Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004).