78

Plastic Pollution and Downstream Impacts

In recent years, there has been an increase in interest in marine

plastics.However,fewstudieshavefocusedonplasticaccumulation

in freshwater systems and rivers, despite their important role in

transporting plastics to the sea (Williams and Simmons, 1997;

Galgani et al., 2000; Acha et al., 2003; Rech et al., 2014).

Plastics production reached 300 million tons in 2014 (Plastics

Europe, 2015). Plastic has many applications and advantages

and is used in almost all economic sectors because of its specific

characteristics – its low cost, durability, strength and lightness.

Unfortunately, it is precisely these characteristics that make

plastics so persistent and widespread in the environment,

causing huge challenges in terms of impact and management

(UNEP and GRID-Arendal, 2016).

Plastic litter is generally subdivided into larger macroplastics and

smaller microplastics, which measure less than 5mm (GESAMP,

2015). Microplastics are either purposefully manufactured (for

example, microbeads in abrasives or in cosmetics) or are the

result of erosion and fragmentation of larger plastic items. The

degradation of plastics depends on physical, chemical and

biological conditions but is enhanced by exposure to ultraviolet

light and air. Fragmentation into smaller particles increases the

dispersal of plastics into the environment.

Environmental concerns over plastic are not only related to

the volume or aesthetics of waste, but mainly to the impact

they might have on humans and other living organisms. Both

terrestrial and marine organisms can experience mechanical

problems, resulting from ingestion and entanglement. Even

when plastic disintegrates into smaller pieces, the polymer

within may not completely break down into its natural chemical

elements. Most plastics also contain additives to improve their

properties such as flame retardants and plasticizers (for example,

phthalates), which can easily leach out to contaminate the

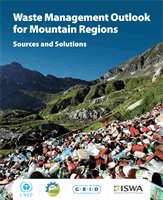

One of the far-reaching implications of waste in mountains, particularly waste that is unmanaged

or poorly managed, is that it might not always stay in the mountains. Solid waste can end up in

rivers, lakes or wetlands after it enters sewage systems, is washed down by rainwater, or blown

away by wind. Lakes, including artificial lakes and reservoirs, can act as temporary storage facilities

for all kinds of litter, but it is rivers that are the key pathways to lowlands and coastal areas – for

water, sediments, pollutants and litter. Once rivers have discharged their content into the ocean, it

becomes ‘marine litter’. Waste that was once disposed of on a mountain can find itself on the floor

of submarine canyons (Tubau et al., 2015).

surrounding environment. Some of these substances are known

to be toxic and cause endocrine disruptions and other potential

risks to living organisms (Oehlmann et al. 2009; Teuten et al.,

2009) including humans (Talsness et al., 2009).

Plastic pollution can also clog drainage systems, which are very

important for channelling excess water and preventing flooding,

especially after heavy rainfall. When water pipes are blocked by

plastic debris, the diverted water can cause local flooding, which,

in turn, has the potential to transport more plastics.

Plastic pollution is directly linked to human activity, population

density and the quality of waste management (Jambeck et al.,

2015). Without proper waste management, even low-density

populations can heavily pollute freshwater systems with plastics.

While there are major uncertainties about the actual quantities

of plastic debris in lakes and rivers, high concentrations of

microplastics have been found even in remote water bodies.

Examples include Lake Hovsgol, a remote lake in a mountainous,

sparsely-populated region of Mongolia (Free et al., 2014); in

fish from Lake Victoria (Biginagwa et al., 2016); in sediments of

remote lakes in the Tibetan Plateau (Zhang et al., 2016); in lake

sediments in Italy (Fischer et al., 2016); in the Laurentian Great

Lakes (Driedger et al., 2015); in the Yangtze (Zhao et al., 2014);

and in the Danube (Lechner et al., 2014).

The lack of available data does not allow for a comprehensive

assessment of the long-term impacts of plastics on mountain

ecosystems and human health. Further research is needed, but

prevention, mitigation and adaptation strategies and policies

should be urgently designed to address identified sources and

pathways to prevent further plastic contamination – including

the dispersal of persistent organic pollutants in freshwater

systems on which human populations depend for drinking water

and food resources.