Reading Matters

Research Matters

CLICK HERE TO RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTSReading Matters | Volume 16 • Winter 2016 |

scira.org|

07

|

(see Table 1 for an overview), a teacher might choose to make

this a much shorter unit of study by sequencing daily instruction

rather than weekly. Additionally, making the series of lessons part

of a consistent writing workshop where students have extended

periods of time to write and share on topics of their choosing on

a regular basis would likely increase student motivation to write.

Initial Attitude Assessment

Before any instruction related to our digital stories project, I

administered theWriting Attitude Survey, or WAS (Kear, Coffman,

McKenna, & Ambrosio, 2000). This twenty-eight question Likert-

scale survey utilizes cartoon images to depict various attitudes

and was designed to measure writing attitudes in grades 1-12. The

scored responses provide both a raw score and a percentile rank

for students based on a national norm and asks questions such as:

“How would you feel if your classmates talked to you about making

your writing better?”and“How would you feel if you could write

more in school?”For the purposes of this study, I examined the

students’raw scores to determine if they had positive or negative

attitudes toward writing. After the initial administration, I found

that 75% of the students strongly disliked writing overall. I also

found that 93% of students strongly disliked revising their own

work or peer reviewing other students’work. The average answer

on a scale of 1-4 with 4 being the most positive was 1.475 for both

revising and peer editing. These results were concerning since

peer-review and revising work are key elements of writing for

publication. Through a series of lessons, the teacher and I modeled

and discussed reasons for editing and revising and emphasized

doing both for publication, in this case through a digital story.

Writing Lessons Prior to Publishing

While ultimately the teacher and I knew the students would

be publishing their work as a digital story, there was a significant

amount of work we wanted to do to help the students grow

as writers

before

they moved into digital writing. As Bogard

and McMackin (2012) describe in their research on integrating

traditional and new literacies, we wanted students to understand

how to plan, draft, and revise as they prepared to create their

digital stories. Since I was not be able to be in the classroom daily,

the teacher would continue having students writing regularly

in between my visits. Each of the lessons I taught connected to

both this on-going writing and our ultimate goal of publishing

a digital story. While I will share the order and details of my

lessons, those wishing to utilize digital storytelling in their

own classrooms do not necessarily have to follow my process

exactly; rather, I hope they will see how digital storytelling can

work seamlessly with more traditional writing instruction.

Lesson one: Prewriting

The week after completing theWAS, we focused our first lesson

on prewriting and using our senses to describe. As a whole class,

we discussed an example of a prewriting strategy as we described

a pig. We explained to students that prewriting strategies would

enable development of their best work, which they would be

publishing as digital stories. There are many ways students can

pre-write, including brainstorming, sharing orally, and using graphic

organizers. We combined a bit of each of these as we conducted

our lesson on prewriting. Students described the pig’s appearance

(size, shape, color), movement, and sound. Examples of student

responses include: 4 legs, 2 pointy triangle ears, medium size, tennis

ball shape nose, black hooves, curly tail,“Oink”, and rolling in mud.

Students recorded these ideas in their notebooks by creating a

graphic organizer. They drew a circle and wrote“pig”in the middle

with lines emanating from the circle with the ideas the class had

collectively shared to describe the pig. Students were then asked

to write a short paragraph describing the pig using at least five

sentences. As I observed the students, I noted that some primarily

focused on the number of sentences that were required instead of

the quality of their writing. While discussing this with the teacher,

we decided to be careful of the language we used when giving

parameters for the writing tasks and would attempt to leave them

as open-ended as possible. We also considered how we might

have modeled writing a short paragraph about the pig and then

having students select a different topic to describe using the senses

strategy so that students were allowed more choice in their writing.

Lesson two:

Using our senses to describe

During the second lesson, we reminded students of our

previous activity describing the pig. We then assigned each of the

five student desk clusters a sense. We gave each student a sticky

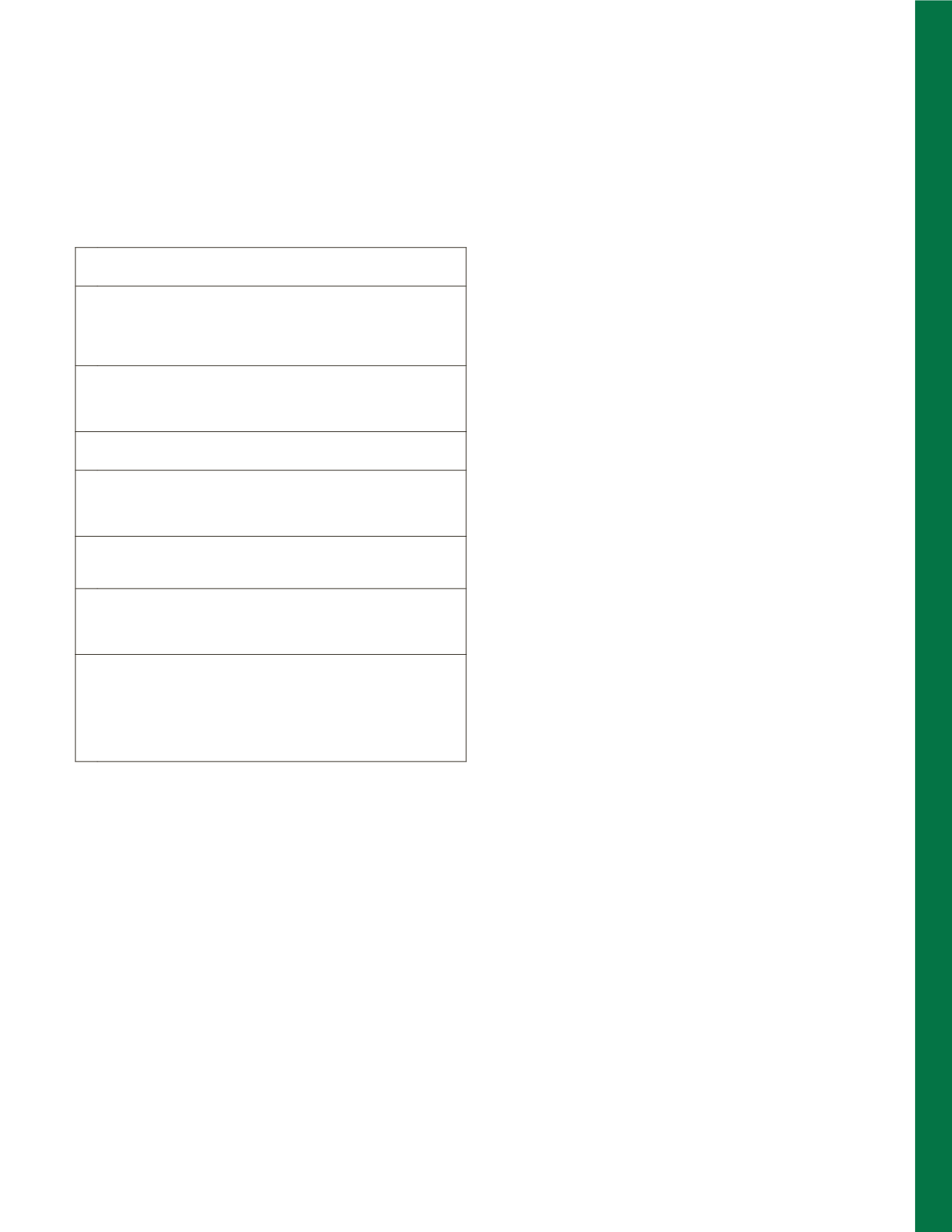

Table 1. Overview of Lessons

1.

Practice using senses for descriptive writing. Introduce prewriting

strategies. Model how to write a paragraph using prewriting

2.

Divide students into groups for each sense (sight, smell, hearing, taste,

touch). Have students write words or phrases describing a weather

patter (rain, snow, sunshine –choose one) on sticky notes. Post notes

on board under corresponding sense. Discuss examples and create a

collaborative description of chosen weather.

3.

Discuss the purpose of editing for publication. Introduce proofreading

marks. Practice editing as a whole class then individually. Emphasize

how everyone makes errors and good writers edit their own and have

other people edit their work before publication.

4.

Students revise an informative paragraph about weather they have

written. Give students feedback using two stars and a wish.

5.

Model how to revise a paragraph about your favorite season. Emphasize

the use of descriptive words and explaining why. Have the students

choose a season and begin the prewriting process by using a bubble

map. Students should continue working on this draft.

6.

Students review peers’writing using a checklist and two stars and a

wish. Encourage some students to share a sentence they are proud of.

Students draw pictures to coordinate with their writing.

7.

Once final drafts are approved, students can begin compiling their

digital stories. Demonstrate how to use the digital storytelling app such

as 30 Hands. Have students create a practice story with a partner to

gain understanding of the application.

8.

Across multiple days, Students create their digital stories by organizing

their pictures and recording their scripts with the digital storytelling

application (e.g., 30 Hands). Students may need assistance by numbering

each picture with corresponding sentence(s). Encourage students to

play back their recordings and edit them as needed. Then students will

publish their stories to create a movie. As the teacher you can download

or upload these movies to share with parents and friends.