www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au

www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au

ACQ

Volume 11, Number 2 2009

73

The home literacy environment is an important influencing

factor in young children’s reading acquisition (Frijters, Barron,

& Brunello, 2000). The use of parent questionnaires such

as the “Early Literacy Parent Questionnaire” (Boudreau,

2005) or an adapted version for parents of children with

Down syndrome (van Bysterveldt, Gillon, and Foster-Cohen,

in press) may be useful for speech pathologists to gain an

understanding of the home literacy context. Developing an

assessment profile that integrates knowledge about the

child’s spoken and written language abilities from varying

sources is recommended.

Intervention

Research has established cost-effective methods to

improve both spoken and written language skills of children

with spoken language impairment. Gillon (2000, 2002)

demonstrated that 20 hours of phonological awareness

intervention significantly improved speech production,

reading and spelling performance for New Zealand children

with spoken language impairment, including children with

severe speech impairment.

An independent replication of Gillon’s (2000a) study was

conducted in London with 5–7 year old British children

who had speech impairment (Denne, Langdown, Pring, &

Roy, 2005). The researchers based their intervention on the

Gillon Phonological Awareness Training Programme (Gillon

2000b), but made some adaptations to the content and

reduced the intensity of the treatment. Denne et al. (2005)

found the intervention was effective in rapidly improving the

children’s phonological awareness development. Consistent

with Gillon’s results, large effect sizes were obtained for

measures of phonological awareness. However, the transfer

of phonological awareness skills to speech and reading was

not evident following the 12 hours of intervention. Denne

et al. highlighted the importance of program intensity and

the need for increased time to ensure transfer effects.

Alternatively, the adaptations made by Denne et al. to the

program content may have weakened the component that

specifically addresses the links between speech and print

that were emphasised in the Gillon (2000) study.

Gillon’s results (2000) are consistent with a large body of

research demonstrating the effectiveness of phonological

awareness training for varying populations. For example; the

following groups have all demonstrated positive reading and/

or spelling outcomes in response to phonological awareness

intervention:

•

older children with specific reading disability or dyslexia

(e.g., Gillon & Dodd, 1995, 1997; Lovett & Steinbach,

1997; Truch, 1994);

•

young children from low socioeconomic backgrounds

(e.g., Blachman, Ball, Black, & Tangel, 1994; Gillon et al.,

2007);

•

children diagnosed with moderate learning difficulties

(Hatcher, 2000);

•

children with Down syndrome (van Bysterveldt, Gillon,

Foster-Cohen, 2009; Goetz et al., 2008);

•

children with childhood apraxia of speech (McNeill, Gillon,

& Dodd, in press);

•

preschool and school-aged native speakers of: English

(e.g., Brennan & Ireson, 1997; Torgesen, Morgan, &

Davis, 1992); Spanish (Defior & Tudela, 1994); German

(Schneider, Kuspert, Roth, & Vise, 1997); Danish

(Lundberg, Frost, & Petersen, 1988); and Samoan

(Hamilton & Gillon, 2005).

A meta-analysis of 52 controlled research studies

in phonological awareness intervention confirmed that

Assessment examples

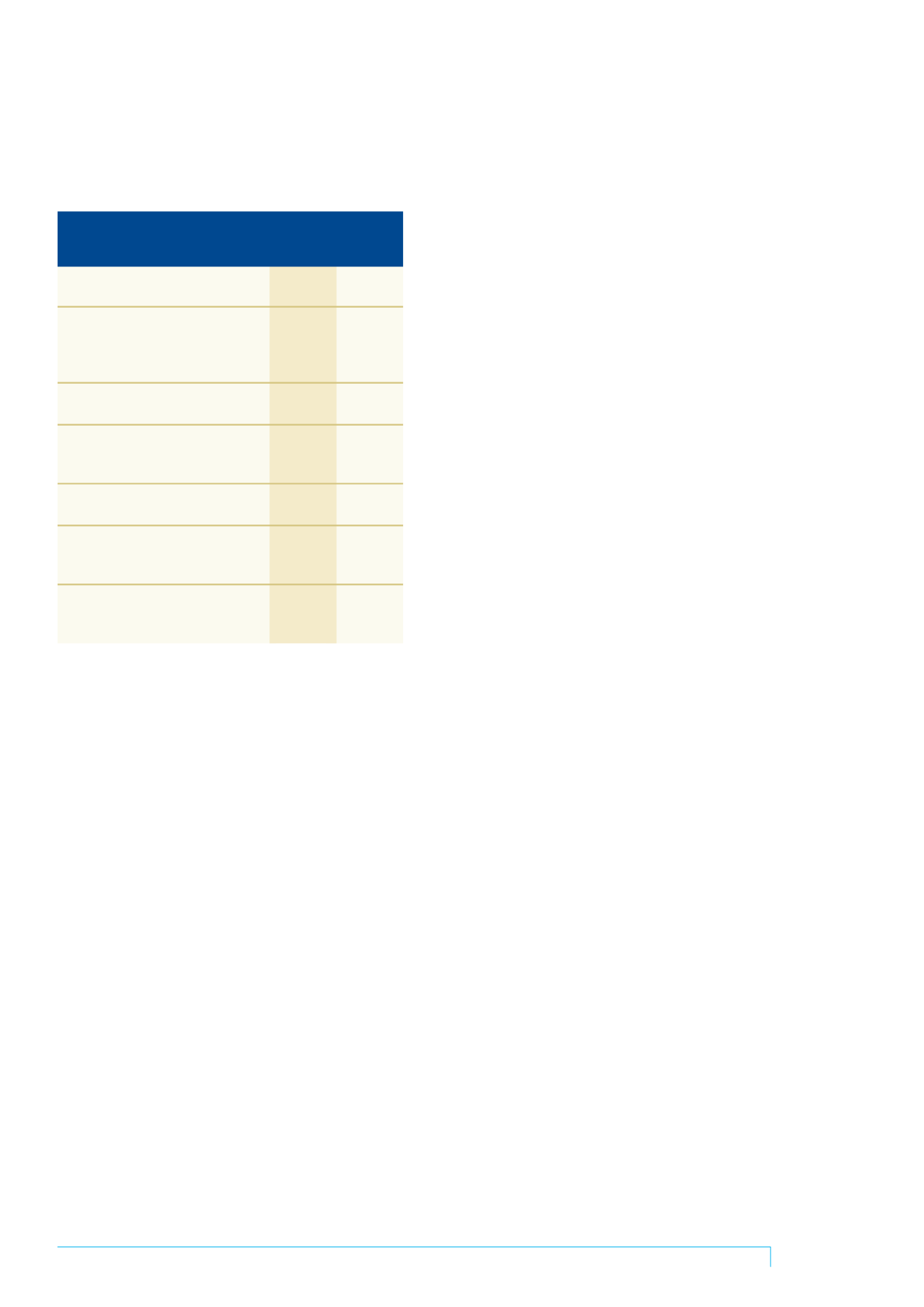

Gillon (2004) and Torgesen (1999) discussed standardised

and criterion-referenced phonological awareness tasks

that may be useful. Examples of standardised assessment

measures are presented in table 1.

Table 1. Examples of standardised phonological

awareness assessment measures that are suitable

across the lifespan

Assessment

Normed Normed

age group population

Preschool and Primary Inventory of

3;0–6;11 Australian

Phonological Awareness (PIPA)

(Dodd,

and British

Crosbie, MacIntosh, Teitzel, & Ozanne,

2000)

The Phonological Awareness Test (PAT)

4;0–7;11 British

(Muter, Hulme, & Snowling, 1997)

Queensland University Inventory of

6;0–12;0 Australian

Literacy (QUIL)

(Dodd, Holm, Oerlemans,

& McCormick, 1996)

Sutherland Phonological Awareness

Grade 1–4 Australian

Test – Revised (SPAT-R)

(Neilson, 2003)

The Comprehensive Test of Phonological

5;0–24;0 American

Processing (CTOPP)

(Wagner, Torgesen,

& Rashotte, 1999).

The Lindamood Auditory

5;0–18;0 American

Conceptualisation Test (LAC)

(3rd ed.)

(Lindamood & Lindamood, 2004)

Informal phonological awareness assessments and the

development of assessment probes are useful to gather

baseline data prior to and during intervention to monitor

treatment effectiveness (see Gillon, 2004, for a discussion of

phonological awareness assessment tools and a critique of

their psychometric properties).

An evaluation of children’s phonological awareness skills

should be carried out alongside other speech and language

assessments. Areas of spoken language development known

to specifically impact upon written language development

should be included in a comprehensive assessment (e.g.,

children’s semantic and syntactic development). Children’s

oral narrative abilities are also related to reading compre

hension performance and oral narrative protocols that

demonstrate optimal language sampling conditions should

be administered to children suspected of having language

impairment (Westby, 1999; Westerveld & Gillon, 1999/2000).

Working with families and teachers

Speech pathologists typically collaborate with families,

teachers, and reading specialists in assessing children with

speech and language impairment. Data collected related

to children’s phonological awareness and phonological

processing abilities should be integrated with teachers’

and parents’ knowledge in areas such as the children’s

print concepts, letter knowledge, and literacy curriculum

assessments, attitudes to reading, reading materials of

interest, as well as visual and hearing abilities. Observing the

child’s ability to use phonology in the reading and spelling

process in classroom activities through analysing spelling

attempts in writing samples or analysing reading errors

when the child is reading aloud provides additional useful

information.